SINCE 2004 the island state of Malta has been a member of the EU and since 2008 they have used the Euro. While these were big decisions for Malta to take, the island has been part of a wider family of nations for thousands of years.

Sat in the centre of the Mediterranean, which itself means 'the centre of the world', Malta has been ruled by many countries. Its language is based on that of Arabic rulers from the 10th century, although, common words like 'hello' come from the Norman conquerors of the 12th.

And so to the present, where, thanks to the 150 years of British rule, beer, pies and red phone boxes abound.

Yet with all these influences, a strong Maltese identity has survived and thrived as I found out earlier this year.

We stayed in an apartment in the old town of the capital Valetta. Built in the 16th century to a grid pattern, the stone-built apartments were raised as the Grand Harbour was fortified by the leader of the Knights of St John, Jean de Valette, after whom the capital is named.

The town sits atop the bony finger of a headland between the Grand Harbour and Sliema. Almost entirely skirted by high walls, the town is a dramatic fortress, at peace now, but for centuries, alternately besieged and embattled.

From its ramparts lies the Grand Harbour. Never was a name so fitting. Here, some of time’s greatest dramas have been played out. From the defiance of the Ottoman's siege in 16th century to the arrival of life-saving convoys in the Second World War, crowds have gathered on its ramparts to witness history being made.

And history is something the island has plenty of. Arabs, Normans, knights, French and British have all left their mark on the island – and this mark is strong in Malta’s eclectic taste in food.

How’s this for a mixed menu? Fried octopus and chips, pasta with rabbit sauce, Maltese trifle and pies.

Rabbit appears frequently, especially stewed. Maltese cooking favours slow-cooked dishes because there was not enough wood to produce fierce, quick heat. Trifle of course is taken from Britain, but pies are the star of Anglo-Maltese gastronomy. Pasties and proper old-school shaped pies with lids are the norm.

They came with beef and onion, chicken and mushroom, or occasionally rabbit and pea. Peas are big here - especially the dried marrowfat variety. They cropped up in said pies and in the deep-fried Pastizzi - a pastry filled either with peas or cheese.

And they were all very fine. The pastry was never too stodgy, was bronze (rather than golden) and the filling was always nicely meaty.

Each invader has left a linguistic mark. The island’s language, Maltese, is the only tongue in the Arabic family to be written in the Roman alphabet.

Place names especially are almost entirely Maltese and betray their Arabic origins, none more so than the old capital. Mdina. Simply the Arabic word for 'city' or 'town' , the inland settlement is walled and is reminiscent of a French medieval town. Its narrow streets have no cars although you can take a horse and trap around its winding streets.

Strangely, although the mark of other cultures is apparent in much of the language, place names are resolutely Maltese, with very few English names - one of which, like in Newport, is St Julians.

Whenever I travel I always learn some of the language of the place I'm going to. Despite knowing many people spoke English in Malta, I bought a (rare) Maltese phrase book and learned a few words.

This effort was wasted. Malta is not like the Netherlands, say, where most people speak a second language. It has two official languages, Maltese and English. This is no bout of wishful thinking as in Ireland, where Gaelic is a national tongue, but only 10% of people speak it. Here, almost all people speak it naturally and well. Nearly all signage is in English. Advertising is in English and coming from Wales, I expected to see a lot of bilingual signs - but these were a rarity.

Interestingly, people tended to speak Maltese between each other and would effortlessly slip into an easy, fluent English when talking to visitors.

It is a talent they are now reaping rewards for as they profit from the ballooning global demand for teaching English.

Of all their many influences, that of Britain, the last, is still the most apparent.

Apart from the pies, there are the red phone boxes and pillar boxes, cast iron reminders of the island's close links to Britain.

British rule began in 1805 and from then, the island became one of the Empire's most important naval bases. Great battleships would steam into Grand Harbour, menacing and grey, sitting stately at anchor as symbols of British naval might.

The high point of this bond was the Second World War when the island was besieged by the Germans and Italians. Thousands of tonnes of bombs rained down on the island, more ferociously than during the Blitz in Britain.

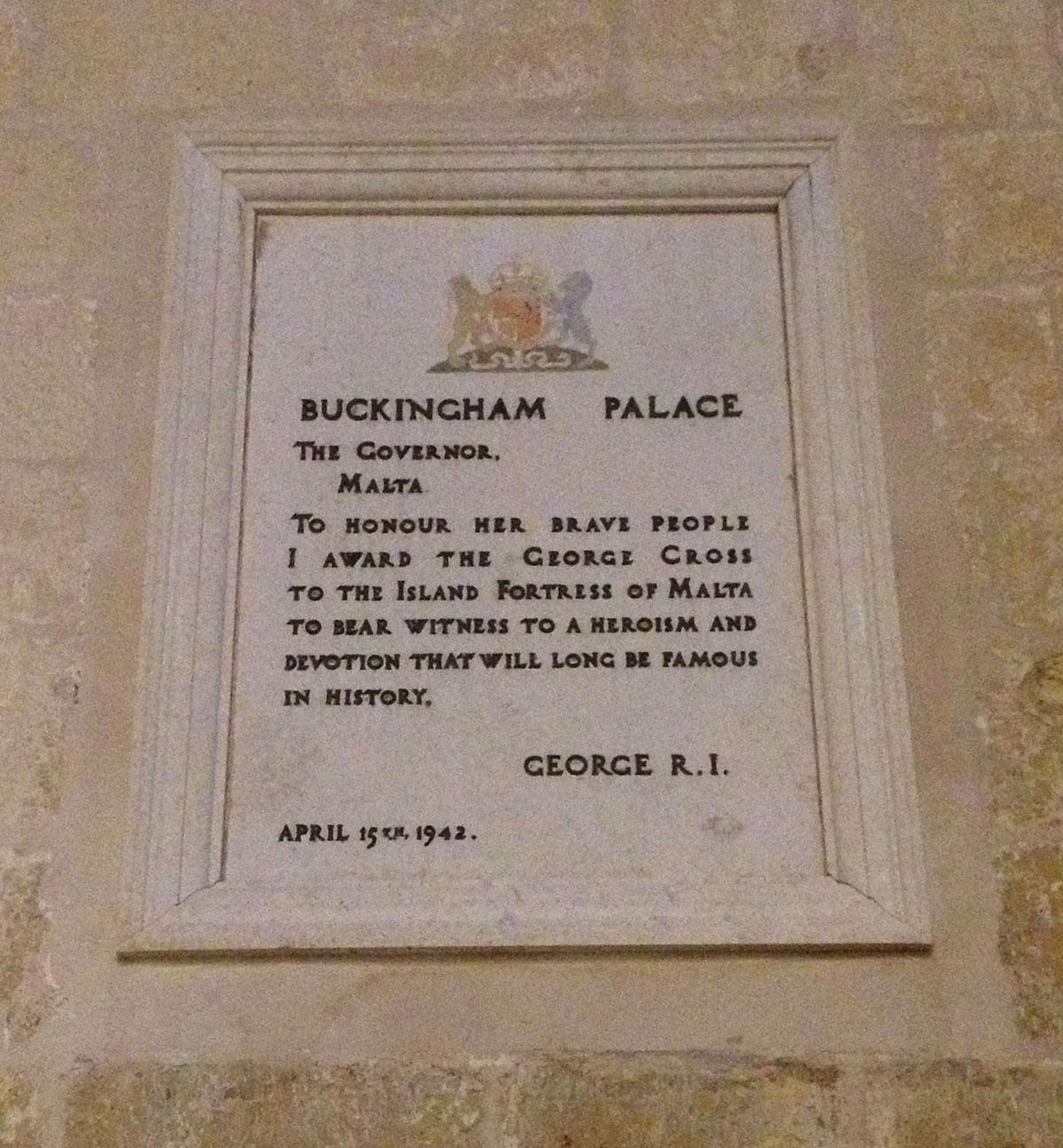

The island held on and a grateful King George VI awarded the island the George Cross in recognition of their bravery.

The military stamp is still there, but somewhat diluted since British forces left in 1979. The Grand Harbour, although hosting great ships of the Maltese and other navies, is quieter now.

Redolent too of empire are the ornate shop fronts dotted around Valetta's streets. The shops, with their cut-glass signage and carved wooden fascias, in their own way echo Malta’s place today. They wear their history stylishly on their sleeve, but the goods within are up-to-date. Resolutely modern yet proud of their past.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here