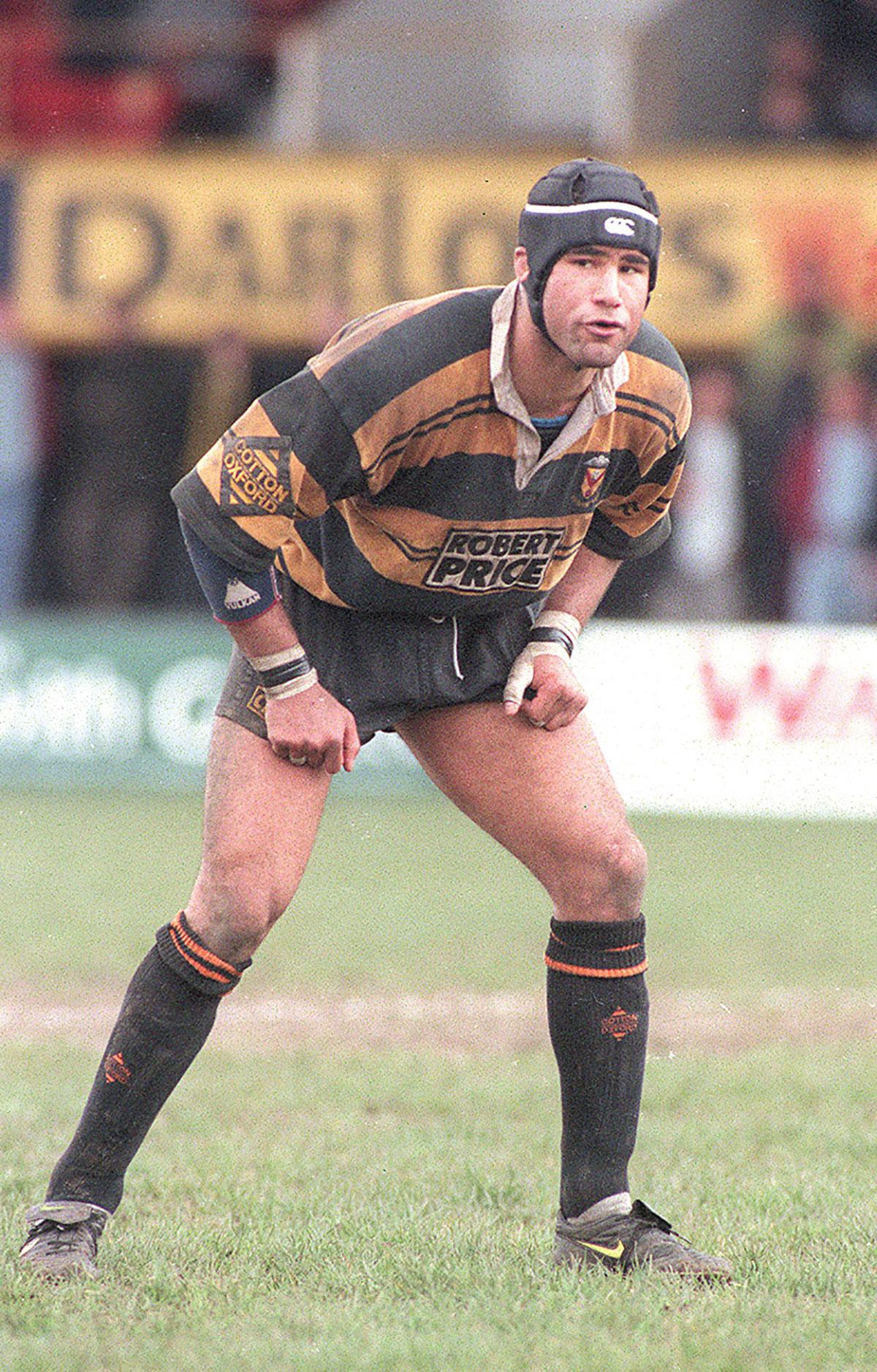

“AFTER leaving Monmouth School I spent a year in South Africa and then came back to university in Cardiff and my first senior rugby contract with Newport.

I was 19-years-old. Professional rugby was very different back then. In fact it was the first year of professional rugby. It was awesome. I was one of the last generation to enter into rugby at that level without planning it to be a career. I’d gone to university and I just loved rugby.

Although the game turned professional the wages weren’t something you could live on.

I guess I’ve always felt grateful for that because I never expected to be playing rugby for a long time. It was just lucky that three years into my degree I broke into the national squad, the Welsh sevens, and had to make a decision.

For me I guess the attitude has run through my life – there’s no point doing something unless you’re going to do it to the best of your ability and I found myself not really giving my best at university and not being the best player I could be.

My folks were really supportive, the university was really supportive. I decided to take a two-year sabbatical to focus on rugby and never looked back. That was 12 years ago.

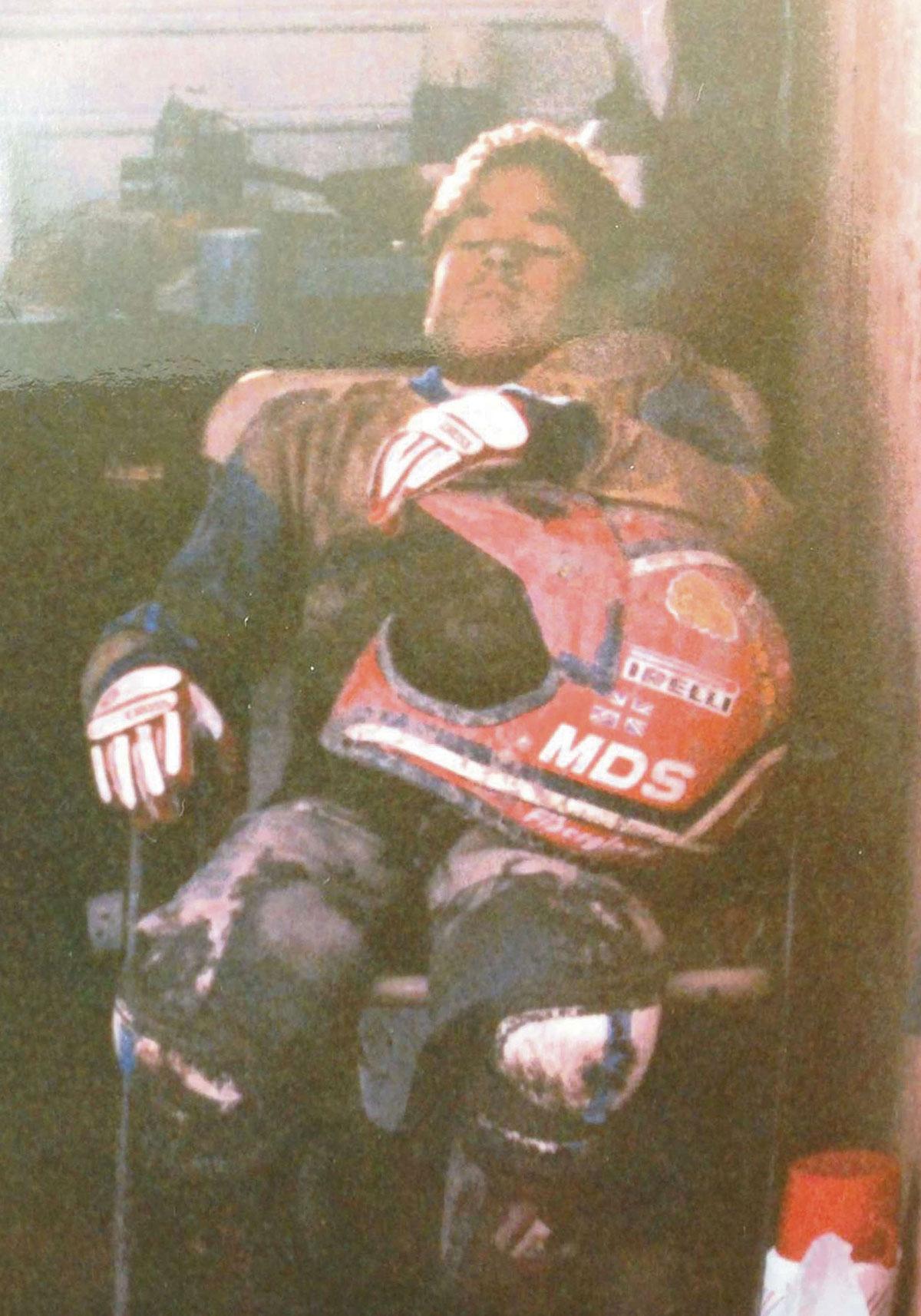

My injury was the darkest period of my life; it was the hardest period of my life. I was battling a lot of negative emotions around that period. I just wasn’t ready to retire. It was pretty scary.

It was daunting not knowing where to go after that. Ironically though, life being life and I think life being wonderful, it was a sentence from my late nan’s funeral that gave me the courage to channel my energy into something positive.

I feel equally privileged that although I’ve worked hard – I’ve worked really hard – I’m privileged that one door closes and another one opens.

With a positive attitude and a good work ethic, I’m able to earn a living doing what I love in the second chapter of my life. I’m incredibly grateful for that.

The last four years of my life have been incredible and a rollercoaster. I have experienced some incredible highs and some experiences that I’m still trying to articulate – standing on the summit of Everest and completing the 737 Challenge, and more recently going to the South Pole.

This last expedition was amazing, having recorded the second fastest time in history. One thing I’m really proud of is being the first Welshman to complete a solo expedition there.

It takes the strain on relationships, friendships, everything. There are some of my mates I haven’t seen for six months because I’ve been training in Peru, for example. It’s not for everyone but I feel really grateful.

It’s really tough to get back to normal. It’s actually one of the parts of the expedition I put a lot of attention into. And this one, particularly, having been to Antarctica last year and knowing how I came back and how difficult it was to readjust. It’s a real hit on the senses.

It’s such a pure existence on an expedition like this. It’s so intense – the nature of the expedition, having to ski a certain number of miles every day, irrespective of the weather conditions and pushing myself to that level.

The only thing that matters out there is managing your body, your tent, your stove – to melt snow to make water – and then your sleeping bag.

That was the only place I could switch off for maybe five hours a day. I did have a few six-and-a-half hours nights, but on average it was five hours.

And you come back and you’re bombarded with information like what to wear, what shirt to wear, all kind of things. It’s tough but I’m not going to blow it out of proportion.

I love Antarctica. It’s insane to be the 19th solo expedition from the coast to Pole – so few people have done it. As love much as I love it, there’s nothing like coming home.

I’m Welsh – I was born in Pontypridd, grew up in Newport and live in Cardiff and South Wales is home to me.

There is a handful of things that I do daydream about. I don’t really daydream about anything material, not really. But I did miss people and interactions. I would daydream about taking my dog, Ben, to Ogmore because it’s home.

There was 14 months of preparation specifically for this expedition, which included a similar expedition through research and development, and that was just to develop the gear that I needed to do it.

The smallest things like getting out your sleeping bag and your legs are so painful because the muscles are so tired it’s painful to straighten them.

I’ve had five hours sleep and the tent’s shaking and dripping and it’s like it’s snowing inside the tent because all my breath has frozen inside the tent, the last thing I want to do is get up. Psychologically it is the toughest part of it.

You’re dropped off on the coast of Antarctica with 28 days’ worth of food and there’s one flight and that either picks you up at the South Pole or it picks you up to bring you home. The only way is home.

I didn’t allow my mind the luxury to drift. Every single minute of every single day is accounted for on an expedition. Mountains are different because you wait for weather, you acclimatise, they’re a little different. They’re intense but not as unrelenting.

Every single day I lived by my watch. It’s got a vibrate function. Every single day I lived off this. My alarm went off at 5.10am. It was routine. Turn the stove off, get ready. At 7am I started skiing. Then my alarm went off at 8.15am, 9.35am, 10.05am, 12.15pm, 1.35pm, 3.15pm, 4.35pm, 5.55pm, 7.15pm, 8.35pm and 9.08pm every day. The times between those alarms were spent skiing with a five minute break.

There’s a longer break – a 25 minute break for lunch and a hot drink. And that’s what I focused on. If I wasn’t skiing I was desperately trying to shave as much time off a break as I could. If I could finish a break and be skiing in four minutes that was a victory for me.

Mentally I have been and am a little frazzled. I didn’t allow myself to think: what’s the point? I’m tired.

I was so disciplined and it is that discipline that is draining.

Although I was out there I see this expedition as not just 29 days. This is 14 months and although I did the last 750 miles on my own, there are a lot of people who played a role as cogs in the machine. Every cog is essential in the machine.

Letting people down is catastrophic for me. When I did get down, and I did, daily, and think negative things, I had to think how I would feel about telling sponsors and friends.

My physio, who works at Sport Wales, gave up her own holiday leave to treat me in Peru so I could get through. How would I have felt if I had given up and then had to tell her?

Or my girlfriend. I missed her 30th birthday and Christmas.

My sister lives in America and I’d planned to be at home for Christmas. Mum and Dad worked so hard to get the house decorated and my sister and her husband and my niece came over. It had been planned months ago. I haven’t seen my sister in a couple of years.

How would I feel if I told Mum and Dad I didn’t fancy it, if they came over and I wasn’t there?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here