In the days when radio was in its infancy, he was a self-taught Blackwood wireless enthusiast who was disbelieved when he picked up the distress signal from the Titanic. Martin Wade tells the story of Artie Moore.

ARTIE Moore was born in 1887, Victoria was still on the throne and he lived in a 17th century water mill. But his fascination for the very modern technology of wireless communication meant that on the night of April 15 1912 when a disaster happened which would be known across the world, it would change his life forever.

As a child, Artie had an accident at the mill badly injuring his leg, which had to be amputated. Perhaps spurred by this setback he developed a fascination for engineering, which saw him make a device so he could still pedal his bicycle while wearing a wooden leg.

The water mill at Gelli Groes was the perfect workshop for the youngster. He used a lathe driven by the water-wheel to build a working model steam engine. Having entered a competition in The Model Engineer magazine, his prize was a book called ‘Modern Views of Magnetism and Electricity’. It was to be the spark which would ignite his interest in radio.

He became known throughout the area as something of a character, with his gadgets like the specially adapted bicycle. Artie’s reputation as teenage boffin was cemented as he began putting up wire aerials for the radio he was building. He strung a long, thin copper cable from the mill, over the nearby River Sirhowy and slung between trees up the hillside to an old barn.

Artie used his engineering skills to store electricity in his batteries using a generator hooked up to the water wheel. He would also charge batteries for local businesses and farmers, who must have come and gazed in wonder at the sparks generated by his radio transmitter.

The thin strand of copper strung across the Sirhowy, near Ty Llwyd farm, would be the magical thread connecting the talented man to the world in a way that was unthinkable to most people then.

He soon became known beyond the Gwent valley when the Daily Sketch featured him on their front page after he intercepted the Italian government's declaration of war on Libya in 1911.

A bigger story was looming in which Artie would play a part.

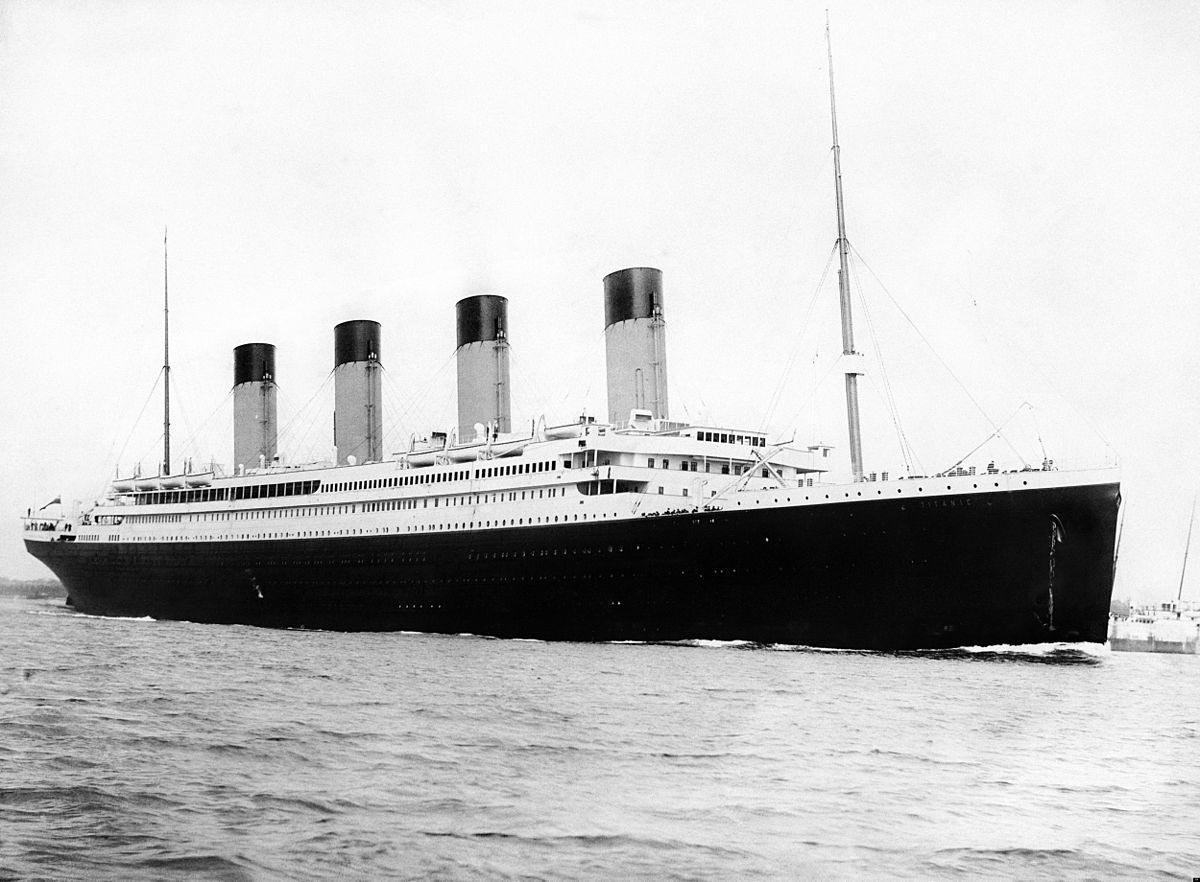

The RMS Titanic was the largest ship afloat when it entered service. Graceful, palatial and vast, she carried 2,224 passengers and crew – some in luxury, but all in comfort. The White Star Line ship was on her maiden voyage, and having left her final port of call, Queenstown in Southern Ireland, steamed out into the Atlantic bound for New York.

The Titanic's radio equipment was manned 24-hours a day sending and receiving passenger telegrams, handling navigation messages including weather reports and ice warnings.

A sound-proofed radio room on the boat deck was manned by two operators and had an aerial strung from its roof along the length of the ship. This strand of wire would send its faint signals which Artie Moore’s spindly cable could pick up thousands of miles away.

Just after midnight on April 15 1912, while steaming in the North Atlantic the Titanic collided with an iceberg 375 miles south of the coast of Newfoundland. As millions of tons of water poured through a massive gash in the ship’s hull, the two radio men frantically sent out their signals.

Meanwhile, in the early morning at Gelli Groes mill, Artie was at his desk, listening. He heard a faint signal in Morse code: "CQD Titanic 41.44N 50.24W." The cryptic ‘CQD’ meant simply ‘Come Quickly Distress". The numbers gave the ship’s position.

It was quickly followed by a further call. Radio was in its infancy and terms familiar to us were new then. The operators, more desperate now used the new SOS signal: "CQD CQD SOS de MGY Position 41.44N 50.24W. Require immediate assistance. Come at once. We have struck an iceberg. Sinking." ‘MGY’ was the radio call-sign for the Titanic.

Moore frantically wrote down the messages, but still they carried on.

"We are putting the passengers off in small boats" said another. "Women and children in boats, cannot last much longer - Come as quickly as possible; our engine-room is filling up to the boilers."

Then, finally: "SOS SOS CQD CQD Titanic. We are sinking fast. Passengers are being put into boats. Titanic."

Moore continued to copy the desperate messages until the Titanic went silent about two hours after the first distress call.

As the signals faded, he ran to the police station to tell them. But the police and everyone else he told didn’t believe him. And who could blame them? He was the one-legged boffin who tinkered with his mysterious contraptions and strung wires across the valley. But they were soon proved wrong. As newspaper reports appeared, they read of the 1,500 people who drowned in the icy Atlantic. They found out too that, just as Artie had claimed, the Titanic had been using the new SOS distress signal.

The skill Artie showed that night was eventually rewarded. As proof came of his fantastic story, a local resident wrote to radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi, who had worked in South Wales, telling him of Moore’s achievement. Marconi came to meet him and offered him a job with his fledgling wireless company.

Two years later, as war broke out, Artie’s talents were even more in demand. He was employed as a technician for the Royal Navy. He supervised the fitting of equipment similar to that which he used on that fateful night on naval battleships. As HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible then steamed 8,000 miles south to the Falkland Islands in 1914 to meet a German naval force off the Falkland Islands, they could easily communicate with home and eachother.

Still working with the Marconi Company he did research in developing the radio valve without which vital advances in wireless technology would not have happened.

After the war he kept working in the field. In 1922 he fitted the first fishing boat to be equipped with wireless equipment and in 1932, he patented the Echo-meter - an early form of sonar.

He retired in 1947, but with failing health, he moved to Jamaica to recuperate. But after only six months, he returned to Britain and died at a convalescent home in Bristol. The end of his days mirrored his most famous moment. As those fateful messages crossed the Atlantic, so did he in the final months of his life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel