Few journalists want to write a novel about their trade but former newspaperman and MCL columnist Nigel Jarrett has had a bash...

Moving to Chepstow many years ago was a means by which Monmouthshire County Life columnist Nigel Jarrett positioned himself for a leisurely look at what it meant to be a journalist on a newspaper.

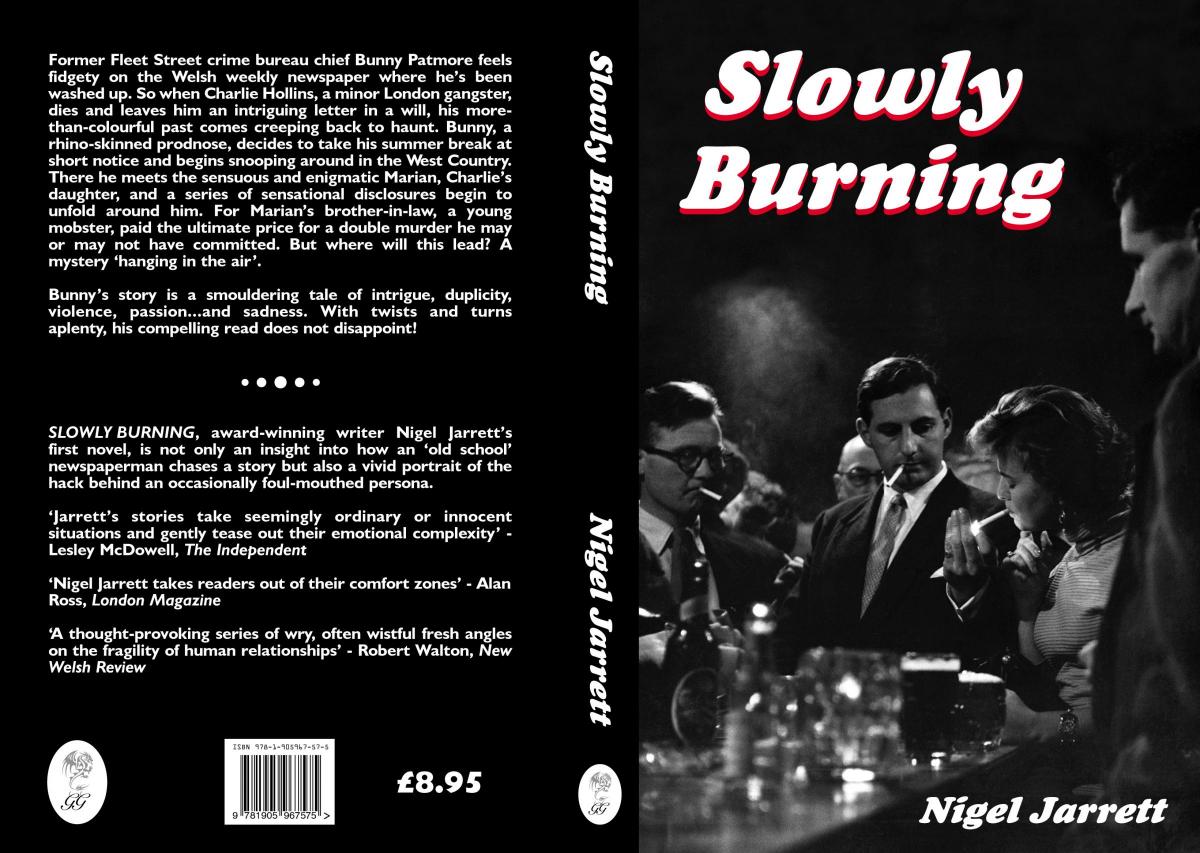

Some of those reflections are now enshrined in his novel Slowly Burning, which has just been published.

In 2014 he moved north-west to Abergavenny, where he now lives with his wife, Ann, a historian and former teacher.

He’d worked for the South Wales Argus for 30 years before finishing there in 2002 and was, among other things, its classical music critic.

“I used to cite camaraderie as the reason I liked working in newspapers, knowing it was a flawed position,” he says.

“Stalin’s death squads must have stuck together and enjoyed a knees-up between decimations, though I hasten to add that I’ve never viewed newspapers as any kind of gulag archipelago. But you do question what social groups get up to in their working hours.”

Adjectives such as ‘questionable’ might apply to Bunny Patmore, the anti-hero of Slowly Burning. Bunny’s a former Fleet Street crime reporter washed up on a weekly newspaper in Wales and is not averse to exaggerating and making up a quote.

In the novel, published by Gwent publisher GG Books, Bunny trades on past fame and notoriety but is bored beyond imagining.

Then he receives an odd letter in the will of a small-time London gangster, Charlie Hollins, who makes an astonishing claim: that he, not the man hanged for the crime, was responsible for a 1940s double murder.

Bunny travels to the West Country to investigate, with the surprising help and connivance of Hollins’s divorcée daughter. They exchange carnal knowledge and indulge a mutual love of Thomas Hardy.

But what Bunny gradually discovers – through the ‘slow burn’ of the title – is just as sensational as the story he hopes to write about Hollins. For Bunny, truth and fiction begin to jostle for attention. He’s also a loner. Not much socialising for him beyond the usual; there’d always be the problem of watching the vulnerable space between his shoulder blades.

When Bunny Patmore talks of writing a story - an honest and accurate newspaper report is always a ‘story’ - in three short sticks, he is referring to the length of newsprint columns, and when he recalls his father, a printer on the Daily Mail, he uses metaphor to explain the workings of Linotype machines, the clattering behemoths that produced metallic text. As well as news stories, Jarrett wrote the fictional sort.

“After winning the Rhys Davies prize for short fiction, I began writing in earnest, though never with much hope of being published,” he explained.

“Then my stories and poems began appearing in obscure magazines. I was pursuing the idea of the reporter as writer - meaning ‘writer’ as fanciful man of letters.

“The routine of much newsroom work, and reporting unappreciated on the hoof in the rain, is miles away from the idea of the journalist as revered scribe,” Jarrett confesses.

“Moreover, many of us have been more second-rate than Fourth Estate. Bunny makes much of the profession’s further demotion from the latter and the former is often a status granted with excessive generosity. Leveson has recently taken it down a few more pegs.”

Part of the backstory in Slowly Burning concerns Bunny’s failed marriage. Although his wife died while they were still together, the union had perished in an alcoholic haze, one of the reasons why Bunny now orders orange juice in the most menacing of bars. Every journalist happily married or in a long-term relationship is by definition privileged.

“It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that when my two children were growing up I was mostly out working, either at evening meetings or at weekend and midweek sports events,” says Jarrett.

“It would be OTT to say that on every Sabbath I was recovering from fatigue, but from Sunday lunchtime till midnight I was already thinking of the next day and what lay in prospect. One just became used to it.

“At the same time, the thrill of identifying and chasing a story and seeing in print is indescribable. You have to do it to understand. Bunny Patmore would know what I mean.”

Patmore was once a heavy drinker, and Jarrett has seen plenty of them, though he’s never been one himself, a deficiency that he says has prevented too many more bibulous colleagues and acquaintances from becoming shoulder-leaning friends.

“There are newsroom tyrants who never touched a drop and can attribute their longevity to the discipline which drink would only have eroded,” he says. “Temperance is the cousin of tyranny.”

Among the undisciplined and intemperate he came across was one who was banned from driving after being breathalysed following an accident outside the office at 8.30am, on his way to the local Assize court.

“Bunny, now a non-smoker as well, is all and none of these,” Jarrett says.

“He belongs in their company but he is not me. For that, I’m both glad and a tad regretful. I never made it to the Modern Babylon, so never trod its gilded pavements or sat on them in befuddled despair.

“Newspapers, the smudgy, rustling and eponymous bringers of tidings good, bad and irrelevant, are on their way out. Newspapers themselves tell us so, while they develop websites for a new era of readers foreign to Bunny Patmore, whose fingers - or, at least, his old man’s - were uniquely ink-stained.”

Having written several million words for tens of thousands of readers during his career, Jarrett views the 70,000 choicer ones of Slowly Burning as stray sprats. He used to have as little hope of seeing them published as he does now of witnessing the printed newspaper’s further longevity, though he says it would be just like a mischievous scribe to have hit upon the idea of this article as a means of plugging them. Banish the thought!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here