Fifty years ago tomorrow, one of the worst disasters ever to happen in Wales saw 116 children and 28 adults die when 150,000 tonnes of coal waste slid down a hillside into the village of Aberfan. A soldier who led a rescue party tells MARTIN WADE of the hellish task that faced them.

RON Birch, now 81, was a sergeant instructor at Beachley Army Apprentices School near Chepstow. A native of Leicestershire, Ron is from a mining background.

His brother, father-in-law and brother-in-law all were mine-workers, so he knows all too well the danger that come with this work.

But it was the by-product of their trade which brought peril that day.

“That Friday lunchtime my wife said she had seen news on TV of an accident in a pit village” he recalls. “We were the nearest military unit to Aberfan and we were put on stand-by in case we were needed.”

“On the Saturday morning we were told to check which soldiers were over 18 years old. As it was an apprentices college, many were 16 or 17 and just as they could not be sent to war, they could not go out on operations like his one.”

To the army and the state, they were not old enough to be sent to war, yet children much younger than them would have faced terror as bad as any faced in battle just hours before.

With other senior staff he led 150 soldiers to Aberfan to do what they could to help.

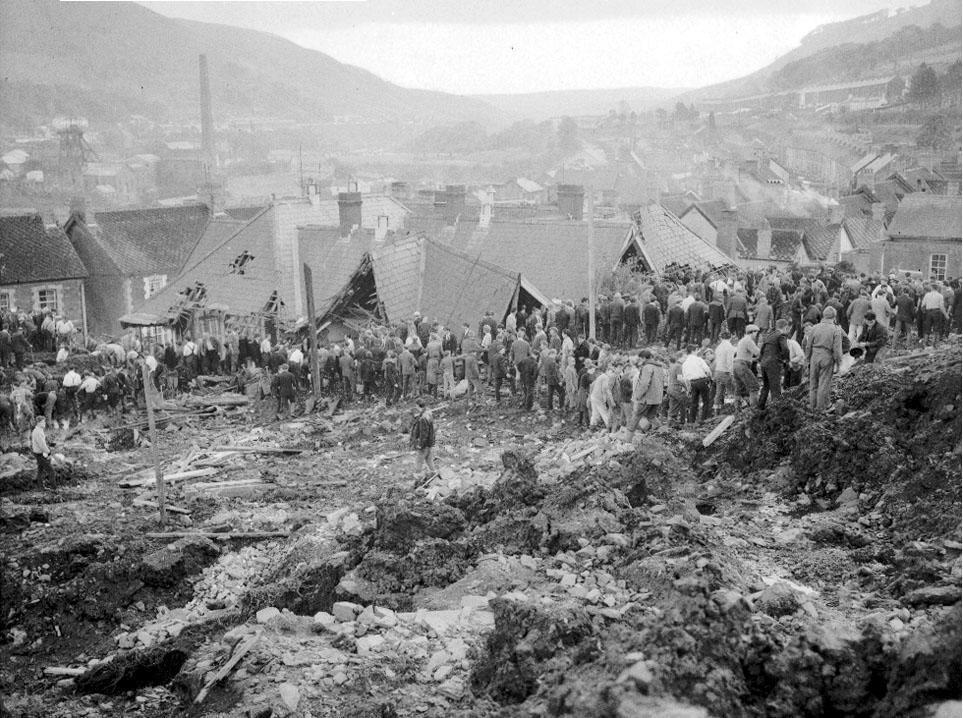

Ron’s memories of the terrible sight that met them are vivid: “A great mass of slurry - thick, deep and black, covered about a mile in length from the collapsed tips to the village streets.”

They found a chaotic scene. “There were people clambering in that mess - villagers still working with hands, spades and shovels.

"There were young mothers stood all around them. Their faces seemed aged with grief.

“Once at street level, you couldn't really see the coal tip, just the people walking around, some crying.”

Ron couldn’t see school itself straight away. He realised that only about 2 1/2 feet of the top of the school building was visible. “The slurry must have been 12 feet deep underneath” he recalls.

“When we got there it seemed very disorganised” he remembers, “there didn't seem to be anyone in charge. There were so many people digging but it wasn't controlled, it didn't seem to be focused.

“There were a few NCB men in suits wandering around and a few policemen” he remembers “They were totally outnumbered and we joined them to help with traffic control”.

This was where Ron and the team of soldiers could help by bringing some military organisation to the rescue and recovery efforts.

“Most of the cars were carrying miners coming to help. They were coming from three different directions and we had to try and bring order to it somehow.” Ron recalls.

There were no telephone lines between the site where the school was and the colliery. Such direction as there was, was given from Merthyr Vale Colliery from where runners had to carry messages. The soldiers set up radio communications between the two sites to speed up links between the rescue teams.

They also put a cordon around the village and made sure only essential people could enter.

The soldiers were soon needed for other vital work. The collapsed tip was still moving, albeit slowly, as rescue and recovery work went on. They had to stop the slurry engulfing the rest of the village.

“We filled sandbags with the slurry itself and built walls to contain it and make sure it didn't slip any further” Ron says.

Over the next few days, the troops worked in shifts with the men toiling eight hours on and four hours off.

By Sunday morning the work became more harrowing and mechanical diggers arrived. “It was then that we started to move bodies from the slurry” Ron says. The last child to be pulled out from the scene was rescued two hours after the slurry had tore through the building.

“By this time” Ron says “It was not a rescue operation. We were there to remove the dead bodies from the coal waste.”

That day saw the excavations managed more tightly. “We put up survey tape to mark out the areas to work on” Ron recalls “and in this way the excavations were brought under control”.

The slurry was being excavated by diggers and loaded onto lorries to be taken away.

It was slow, painstaking work. Miners had put up temporary lighting and the work carried on day and night. “We would probe for bodies and then the digger would remove some earth if there were none.”

When the soldiers found a body, they would carry it to their Land Rover where they would be covered. They would then then drive them to a nearby chapel which had become a morgue.

There they were washed, cleaned and laid out so that in sudden death, dignity could be given to them. Ron says: “No mother could be allowed to see their children before we had done this dreadful job.

“We pulled around 60 bodies from the slurry.”

The young soldiers who, although barely adults themselves, acquitted themselves well in this blackest of tragedies where so many children had died.

Ron was proud of them: “They wanted to get on with the job and help people. They were young lads and they did it well.”

They toiled at their grim task there for five days and just before they left Aberfan many of the grieving parents came to thank the soldiers for their efforts.

Ron remembers how the grime from the coal and slurry marked their hands for days afterwards. But as it eventually washed away, the memories of that hellish job remained. As we talked he went quiet and became distant, but then said: "I've got a lump in my throat just thinking about it. It's a subject very close to my heart."

And it stays with him still. Ron has been back to Aberfan many times. “My wife and I first went there 18 months after the disaster” he recalls. “It's such a tranquil place - I think it's beautifully done.” The peace of the surroundings contrasts with the violence of what happened that day.

"The tips are gone, so is the colliery and the school, but most importantly so are all those children."

He does take some comfort from the help they were able to give, but this is scant relief. "I'm glad we could do something to help the village and those poor people, but by the time we reached the scene we could not save any lives.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel