Continuing the tale of the Aberfan disaster 50 years ago, MARTIN WADE looks at the warnings and at the guilt and the selflessness of those involved.

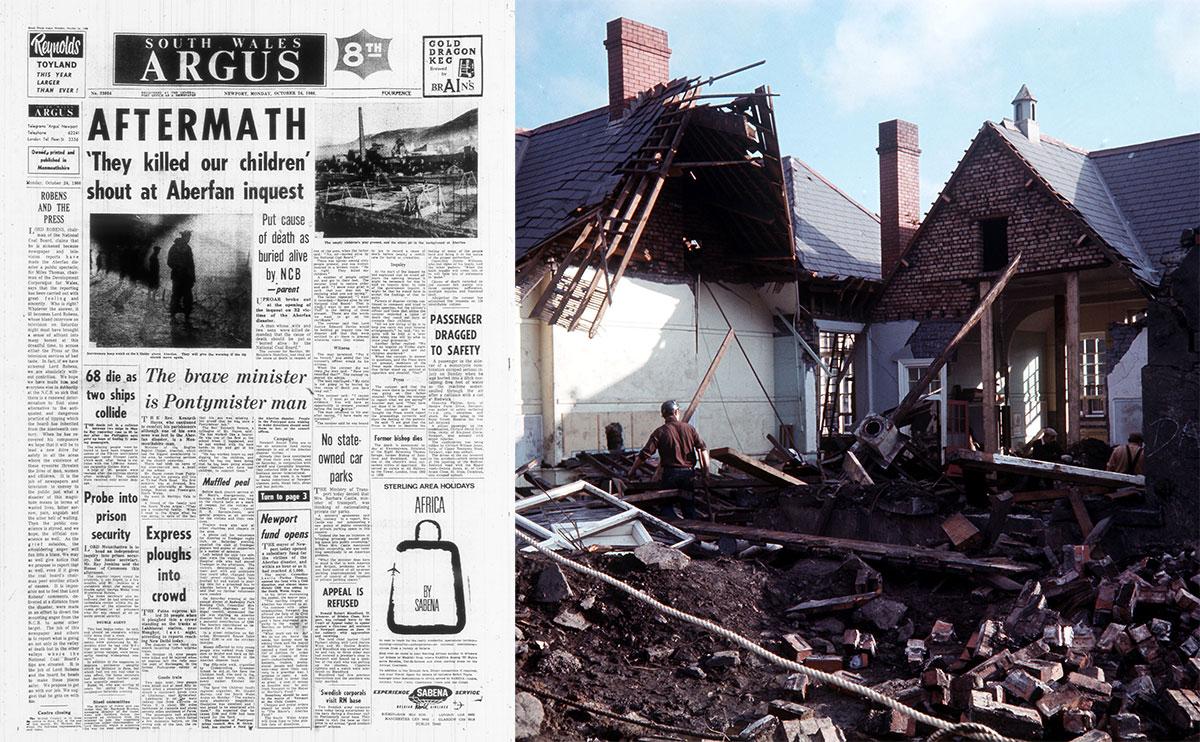

In the days following the disaster, the Argus told of how people had warned of how unsafe the tip was and how the NCB tried to avoid blame for the tragedy. But that blackest of times had seen the people of Gwent and South Wales show great selflessness.

We were told of the anger felt in Aberfan that despite warnings, nothing had been done about the tip years ago. One man at the scene told how "it had been piling higher and higher and with a stream filtering through beneath it. It was always liable to shift. Now it has happened with these terrible results."

The wife of Mr Beynon the schoolmaster told how he had once said if ever the tip collapsed, the school would be the first to go. His grim prophecy had been proved right.

On this awful day, the best and most selfless acts were seen. Among those who went to help from Gwent were twenty Newport firefighters. They had been on their day-shift but went to the scene where they dug until four o'clock on the Saturday morning. Others who were on leave joined them later as did colleagues from Pontypool.

Newport civil defence workers were mobilised, with 100 members moving out in three sections within twenty minutes of receiving the call.

Help came too from beyond South Wales. People began arriving at Newport railway station on the Friday night. One medical student at St Batholomew's Hospital arrived from Paddington at 1.20am. "I felt I just had to come" she said. All she had was her return ticket and three shillings." Also on the train was a man from Southend who was on holiday when he heard news of the disaster. "I've had experience of civil defence work and thought I might be of some use" he said.

Hundreds of people volunteered to give blood, with sessions attracting two or three times the normal number.

At St Lawrence Hospital in Chepstow, a team of doctors were expecting to receive “at least 20 casualties.” Hours after the disaster, he said they were standing by and expected them at any moment. “There may be more than twenty” he added ominously “we don’t know.”

Ambulances from the hospital sped from Chepstow as Monmouthshire Police too stood by.

As many rushed to help, others thoughts turned to shifting the blame. By Monday, the mood in South Wales had turned from horror to anger, with the finger pointing squarely at the National Coal Board who ran the nationalised coal industry then.

Its chairman, Lord Robens, said he was "sickened" at the way newspaper and television reports had made the Aberfan disaster into a "spectacle". The Argus felt it and the press, had nothing to apologise for. "If we have sickened Lord Robens we are absolutely without contrition" it said. "We hope we have made him and everyone else in authority at the NCB so sick that there is a renewed determination to stop the dangerous practice of tipping."

“As the grief subsides” it warned, “the smouldering anger will fan into a blaze."

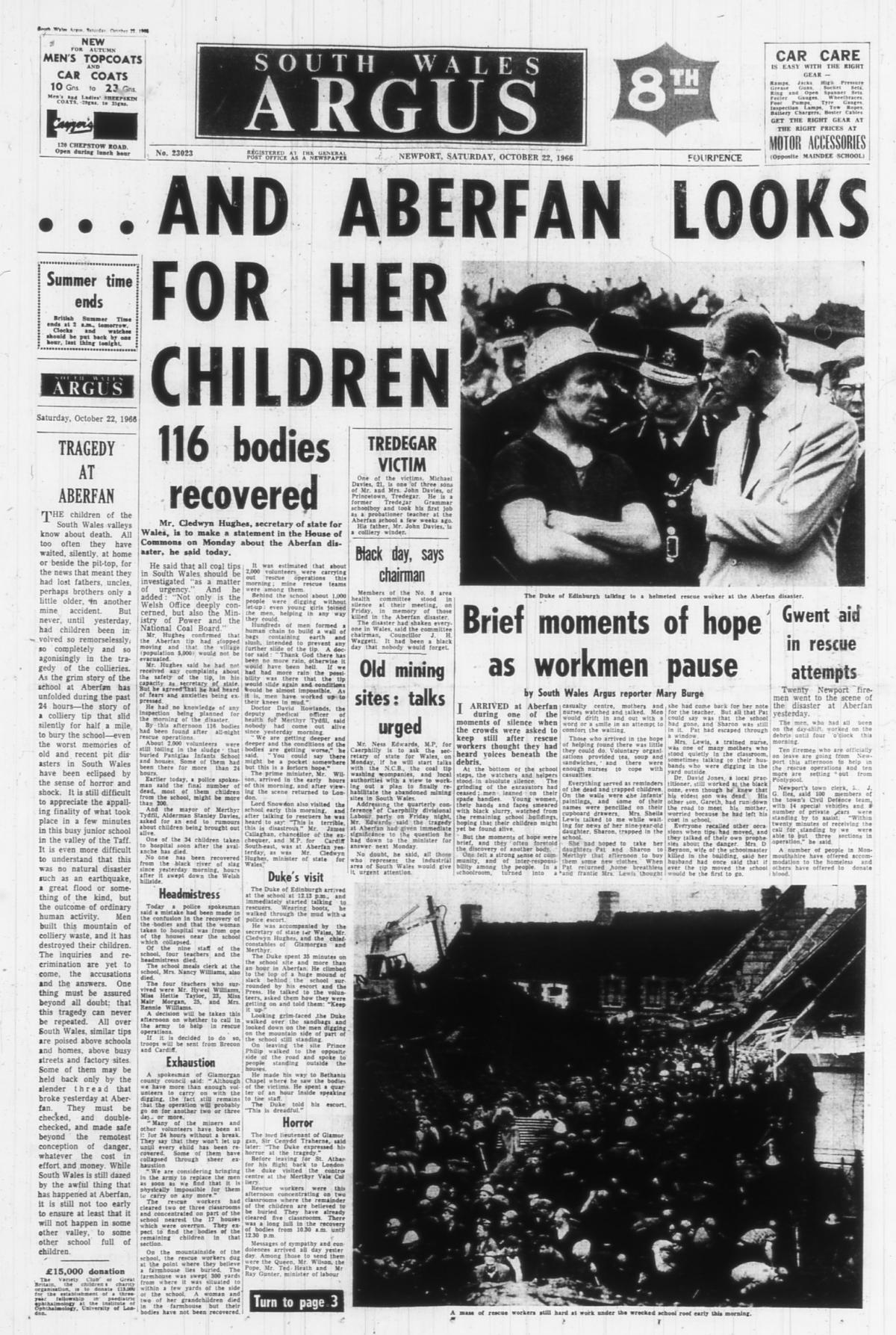

On the Saturday, the Argus reflected on the horror of the day: "The children of the South Wales valleys know all about death. All too often they have waited silently at home or beside the pit-top, for the news that meant they had lost fathers, uncles or perhaps brothers in another mine accident. But never, until yesterday, had children been involved so agonisingly in the tragedy of the collieries. IT added: "Even the worst memories of old and recent pit disasters in South Wales have been eclipsed by the sense of horror and shock."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel