LESS than two weeks ago, organisations and industries around the world were subject to a co-ordinated cyber attack.

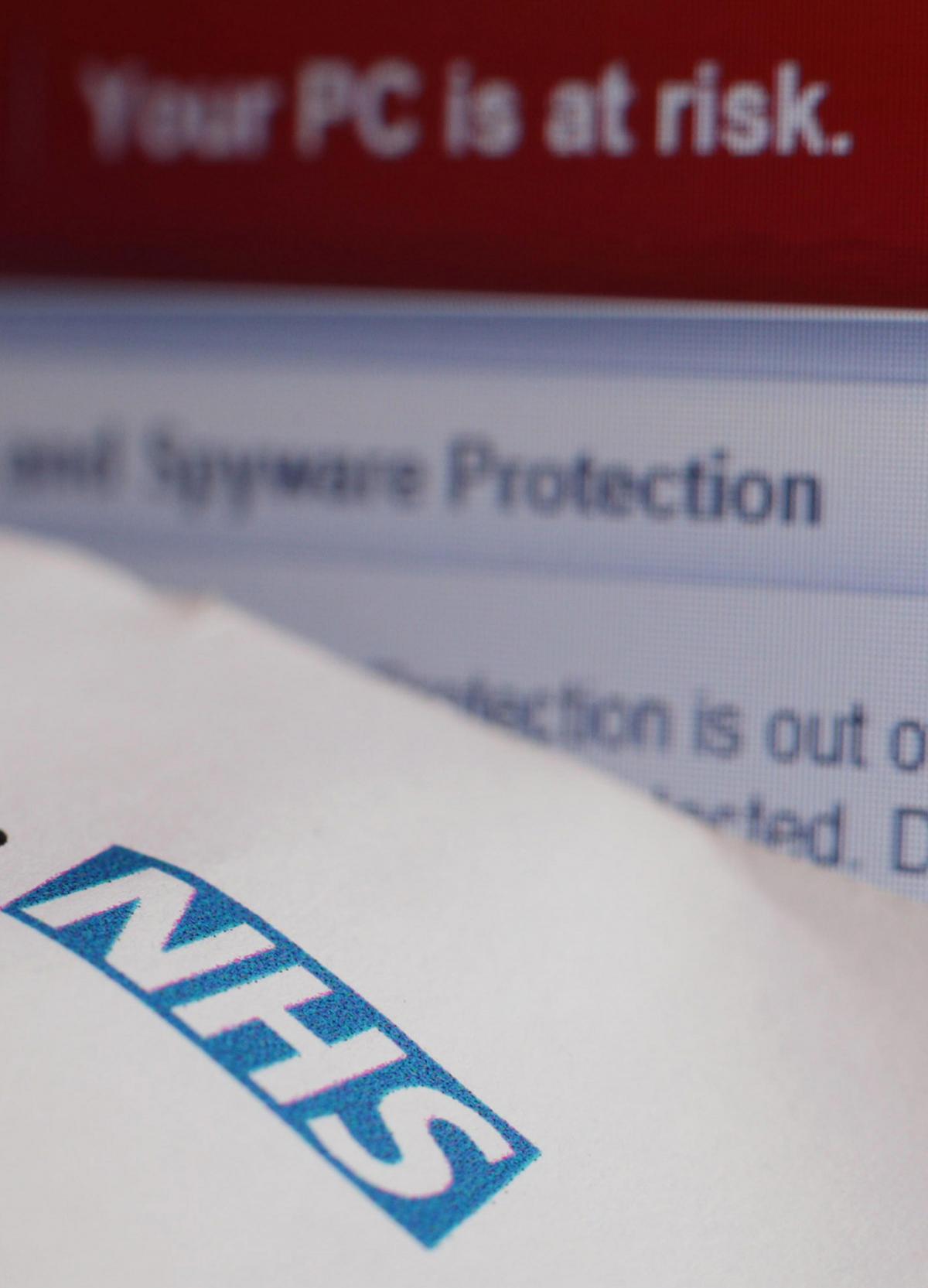

On Friday May 12, ransomware codenamed ‘WannaCry’ infiltrated and infected machines in more than 150 countries – including the UK.

Sensitive computer files were encrypted by the hackers and demands for ransom payments were requested.

Last week, law enforcement agency Europol said it was the “largest ransomware attack observed in history” with around 200,000 victims.

Hospitals in England and Scotland were some of the high-profile victims, with a fifth of trusts unable to accept emergency patients in the days following the attack.

Many believed that NHS networks were left vulnerable because they were still using outdated Windows XP software.

Hospitals in Wales came out of the other side unscathed though, largely due to what first minister Carwyn Jones called “resilient defences already in place”.

Speaking in the aftermath of the ransomware attack, he said: “To continue to protect NHS Wales from disruption a number of extra security controls have been put in place.

“This included temporarily blocking all external emails sent to NHS Wales and applying new anti-virus definitions and patches to both national and local systems.

“Where the ransomware has been detected, immediate remedial action has been taken to prevent the spreading of the virus. This has ensured that no patient data has been compromised or lost.”

Remarkably, there were no reports of the incident impacting on patient care anywhere in Wales, but precautions remained in place as recently as May 18.

Welsh Labour leader Mr Jones added: “I would like to thank all of the IT Teams across NHS Wales and the wider public sector who have worked tirelessly throughout the weekend to protect our public services.”

It was 22-year-old Marcus Hutchins, a young British computer expert, who grabbed the headlines in the wake of the attack – having activated a “kill-switch” in the WannaCry code to slow its effects on computer systems around the world.

But who were the people behind the protection of NHS services in Wales?

The NHS Wales Informatics Service, a public service organisation, supplies more than 70 software services to users across NHS Wales and to other parts of the UK.

Upon catching wind of the WannaCry attack, a major incident room was set up at the service’s Cardiff office – one of five in Wales – and additional monitoring was ordered across the country.

A spokeswoman from the service said: “At the NHS Wales Informatics Service we constantly provide real-time monitoring of NHS Wales’s digital services and IT systems, all of which are designed to have strong security measures.

“In addition we immediately put in extra security controls and co-ordinated the effort to protect our national and local systems, liaising closely with senior management from across NHS Wales.

“Our aim was to ensure that clinical staff can and indeed should continue to use digital solutions to support the delivery of care.”

NHS Wales was in fact attacked by the virus but monitoring software and processes identified each attack, allowing the Informatics Service to isolate and kill the virus.

In total, 37 computers were investigated as being suspected of having the virus but only seven were infected with the malware out of 55,000 computers in use across NHS Wales.

Despite the threat having seemingly subsided in Wales, the Informatics Service are urging suppliers and partners to ensure that local systems are protected and that staff remain aware of the “on-going need” to protect the IT systems.

The spokeswoman added: “Staff across Wales are urged to remain vigilant against the threat of cyber-attacks and to report any suspicious or ‘spoof’ emails.

“The message is think before you click.”

In Newport, the next generation of cyber security experts are being trained at the National Cyber Security Academy (NCSA) at University of South Wales (USW).

According to Gareth Davies, a senior lecturer in computer forensics and cyber security, the WannaCry attack was a “zero day exploit” – a virus that is launched announced, leaving organisations unable to update or patch their systems in time to protect themselves from it.

Mr Davies admitted to being “saddened at seeing” the NHS being targeted but said he “wasn’t surprised” that it had happened.

“This was a very sophisticated form of attack, a new version of an attack we have seen in before,” he said.

“Previously, attacks targeted via email systems through phishing emails that appear in the form of mundane emails, say from a DPD delivery.

“This attack was different in that someone took that and weaponised it to create a worm, a piece of code that is intelligent enough to understand its environment.

“When this malware worm connects with a computer, it will work its way through the system and see what else it can connect to.

“The operating system is the main eco-system of the computer. If that develops a little hole, we apply a ‘plaster’ over that hole, in the form of a patch.”

In the case of the NHS in England and Scotland, the use of connected networks – linking GP surgeries to main hospital infrastructures – meant that the virus could navigate it with relative ease.

But Mr Davies disagreed with the assumption that NHS systems were outdated, despite the age of the Windows XP operating system used.

According to the expert, the NHS has an agreement with Microsoft which sees the organisation’s systems receive regular updates for the operating system – despite support for XP systems used by the public being withdrawn in 2014.

Programmes running on NHS computers, such as those holding patient records, are also dependent on the operating system first introduced in 2001.

Mr Davies added: “I don’t know how many machines there are in the NHS but if those running XP are working then as the saying goes, if it isn’t broke don’t fix it.

“It’s hard to guess how much money it would cost to completely update the NHS’ computer systems.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s XP or Windows 10, if it’s working for the NHS then they wouldn’t want to necessarily stop that and spend money on updating the tens of thousands of computer systems across the board.”

While prominent organisations such as the NHS bore the brunt of the attack, concern does remain for the safety of smaller businesses.

While not even the experts can anticipate a “zero day” attack, Mr Davies said that there are three main things that businesses of all shapes and sizes can do to defend themselves from cyber attacks.

“I like to call it an old crime in a new environment – it’s extortion as it gains access to sensitive files and effectively holds it ransom,” he said.

“The first piece of advice I’d tell businesses is to make sure that the auto-update feature on Windows or Mac system is always running.

“Secondly, I’d make sure that their computer systems are running the most up-to-date. I’d aim for updating it on a weekly basis but auto-updates are default most of the time.

“Finally, it’s important to have a back-up to store your critical data such as a physical hard-drive or similar off-site backup. Most SMEs know this as business continuity planning.”

The LEBC Group, a national impartial financial advice (IFA) agency, has led calls for political parties to prioritise protecting the public from cyber crime in their campaigns ahead of the General Election on June 8.

While not explicitly referencing the ransomware attacks, other forms of cyber attacks such as identity theft and scams have been earmarked as serious threats in light of what LEBC has called an “unprecedented increase in scams”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel