Diana, the Princess of Wales was a mother, a sister and a daughter. She was an ambassador for stellar causes and even ranked as the third greatest Briton – behind only Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Winston Churchill – in a 2002 poll. But the princess was a friend and inspiration to millions who never met her as displayed by the public outpouring of sorrow and affection in her death. STEVEN PRINCE looks into the events surrounding her death on Sunday, August 31, 1997.

IT IS difficult to comprehend, ahead of such an event, how the impact of a fatal road traffic incident in Paris can have such an everlasting and profound effect on the national psyche.

Miles away from the shores of Wales and the wider United Kingdom, in the early hours of Sunday, August 31, 1997, an incident of such improbable magnitude was unfolding and set to shock the nation irrevocably.

The previous day – Saturday, August 30 – has been consigned to history as another, forgettable day at the tail end of the summer.

The South Wales Argus carried the story of Ruth Jones, who delivered her granddaughter in Cwmbran on the front page, along with Gwent crime stats and a family’s heartache at the death of their loved one - Sean Harris.

Newport County AFC were plying their trade in the seventh tier of the football pyramid, the Newport Gwent Dragons – now just Dragons – were six years away from their initial genesis and the Newport was five years from becoming a city.

The death of Diana, Princess of Wales – the woman who would have been queen had it not been for the dissolution of the royal marriage – would change everything.

Since her wedding to Prince Charles, the heir to the British throne, on July 29, 1981 – an event viewed by an estimated 750 million people worldwide – the princess held a special place in the minds of millions .

Over the next 16 years of her life, the princess would illustrate arguably her most endearing characteristic - her humanity and normality while living among one of the world's most famous dynasties.

With the birth of her sons William and Harry in 1982 and 1984 respectively, she was able to exude to the public the face of the doting and happy mother.

The princess also became the face of many charities – which added to her prestige in the eyes of the nation – and revered for her role in the campaign to rid the world of landmines.

But her public separation and eventual divorce from the heir apparent, a little over a decade after the birth of her second child, on August 28, 1996, showed another more morose and troubled side to the princess.

And one year on from that, she would be killed in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris alongside Dodi Fayed, the son of the then-Harrods and Fulham FC owner Mohamed, and the driver of the Mercedes-Benz Henri Paul.

Only one person would survive the crash which killed the princess – Mr Fayed’s Welsh bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones.

The car which was carrying the princess left the Ritz hotel at around 12.20am on Sunday, August 31 via a rear exit to avoid the paparazzi waiting outside.

Roughly three minutes later, the driver lost control of the car and it crashed into the 13th pillar of the tunnel at around 65mph before smashing into the wall backwards after spinning.

She was removed from the Mercedes-Benz at around 1am following the arrival of the Parisian emergency services and was taken to the Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital.

The princess arrived there at just after 2am and died from her injuries at around 4am.

As Wales and the wider UK awoke, news of the princess’s death reached the homes of the nation and with it arrived a palpable sense of grief and astonishment.

Normal television programming across the five terrestrial channels was suspended as a result of the crash as news from Paris was still coming in.

The body of the princess was bought back to the UK on the day on the crash by her former husband and her two sisters – Lady Jane Fellowes and Lady Sarah McCorquodale.

As for the Argus, the first edition of the paper to go print in the aftermath of the princess’s death was Monday, September 1 – a special edition under the headline ‘A nation mourns’.

Moving through the week, each of the following Argus front pages carried headlines about the death of the princess – September 2: ‘Tribute fund is set up for Diana’; September 3 – ‘Tipped off by our press?’; September 4: ‘Unique day for a unique person’; September 5: ‘The nation prepares’ and September 6: ‘Farewell to our princess’.

In the midst of all the coverage, the papers were comprised of stories regarding cancelled events such as the Brynmawr Carnival which was postponed until September 20 and the first floral tributes in Gwent, which began to bloom up from September 2.

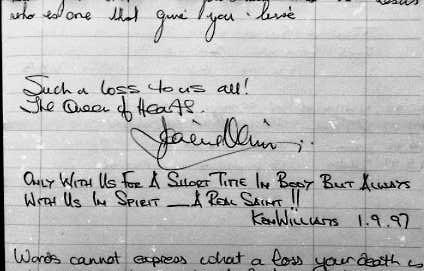

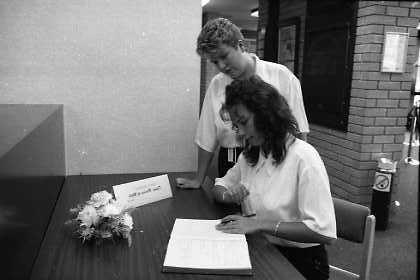

The papers were filled with pages upon pages upon pages of personal tributes to the princess and pictures of people signed books of condolence across the entire region.

On the day before the funeral, even the words to Elton John’s special version of ‘Candle in the Wind’ were published in the Argus.

The funeral of the princess took place the following Saturday – September 6 – after the body was returned to the UK.

Throngs of mourners – an estimated three million – converged on the capital to pay their respects as the coffin passed through the streets of London and a projected figure of 2.5 billion people watched the funeral worldwide.

The following Sunday was a rare occasion were the Argus went to print for a Sunday edition with the special ‘A tribute to Diana’ paper, containing a 12-page pull out.

Incidentally, the first copy of the Argus - either the first or final editions - not to carry a front page story regarding the death of the princess was Thursday, September 11 - which would become another infamous day for all the wrong reasons.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel