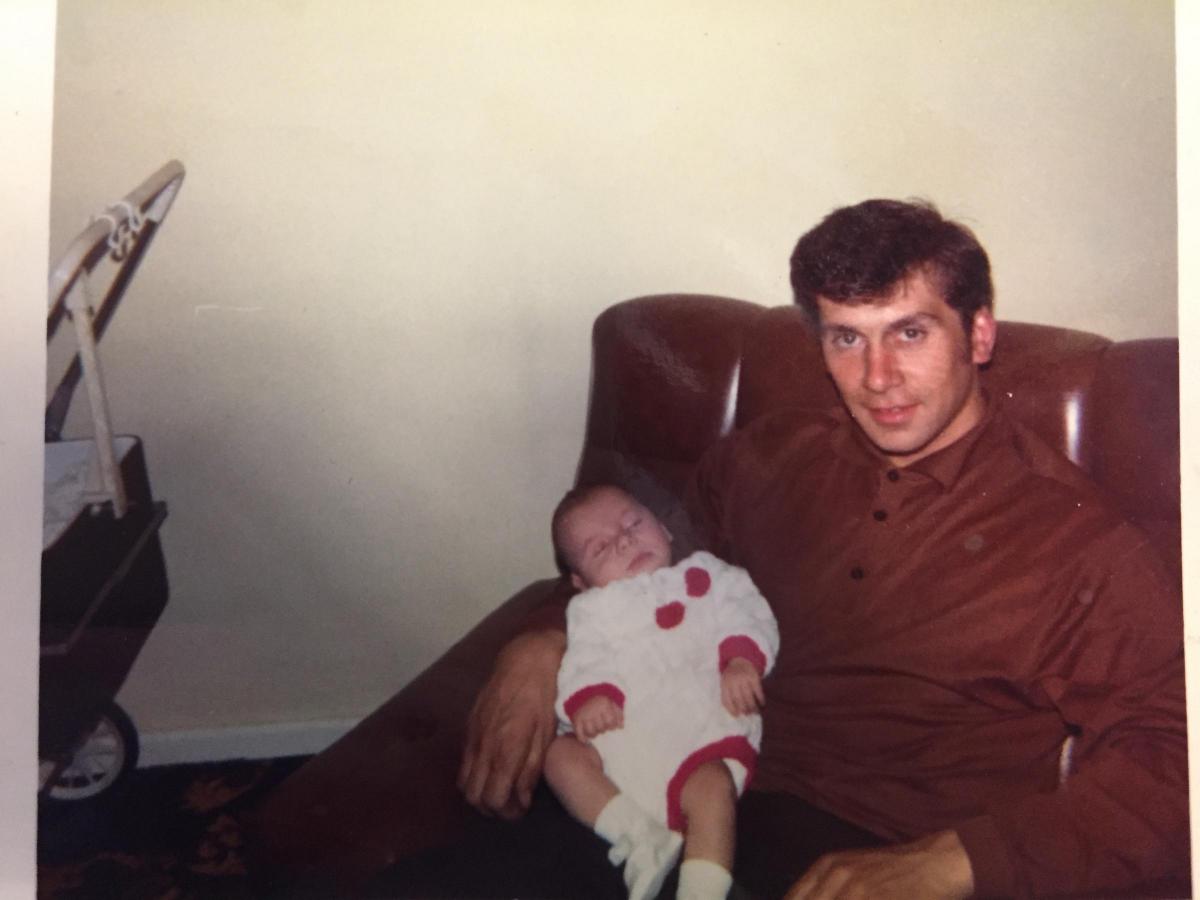

WHEN Graham Chilton died of the asbestos-related cancer mesothelioma, his son Leigh sought justice for the retirement his father was robbed of.

He has achieved it in the form of an undisclosed settlement, but believes there are many other families with loved ones suffering, or who will suffer, the ravages of a cruel disease through exposure to asbestos at work. He urges them to seek justice and crucially, expert help.

Graham Chilton from Pentwynmawr, near Newbridge, was diagnosed with mesothelioma in August 2012. Two months later, he died. Earlier that year he suffered shortness of breath and a chesty cough, and was found to have fluid on his lungs. He then developed pain in his chest and a shoulder, followed by stomach pain.

After various medical examinations, a scan revealed shadowing on his lungs, later diagnosed as incurable mesothelioma. His death at 65 left his only son Leigh, with whom he lived, struggling to come to terms with suddenly being on his own. His mother died in 1997.

It is thought Mr Chilton was exposed to asbestos when working for Newport Forge. He worked mainly at the firm’s Bedwas-based engineering works, starting in 1971, with maintenance work a part of his role. Symptoms of mesothelioma often do not appear until decades later.

He also worked at other sites, including one in Rhymney, where it is believed his role involved lining ovens, cutting asbestos sheets to size and using asbestos ropes as links.

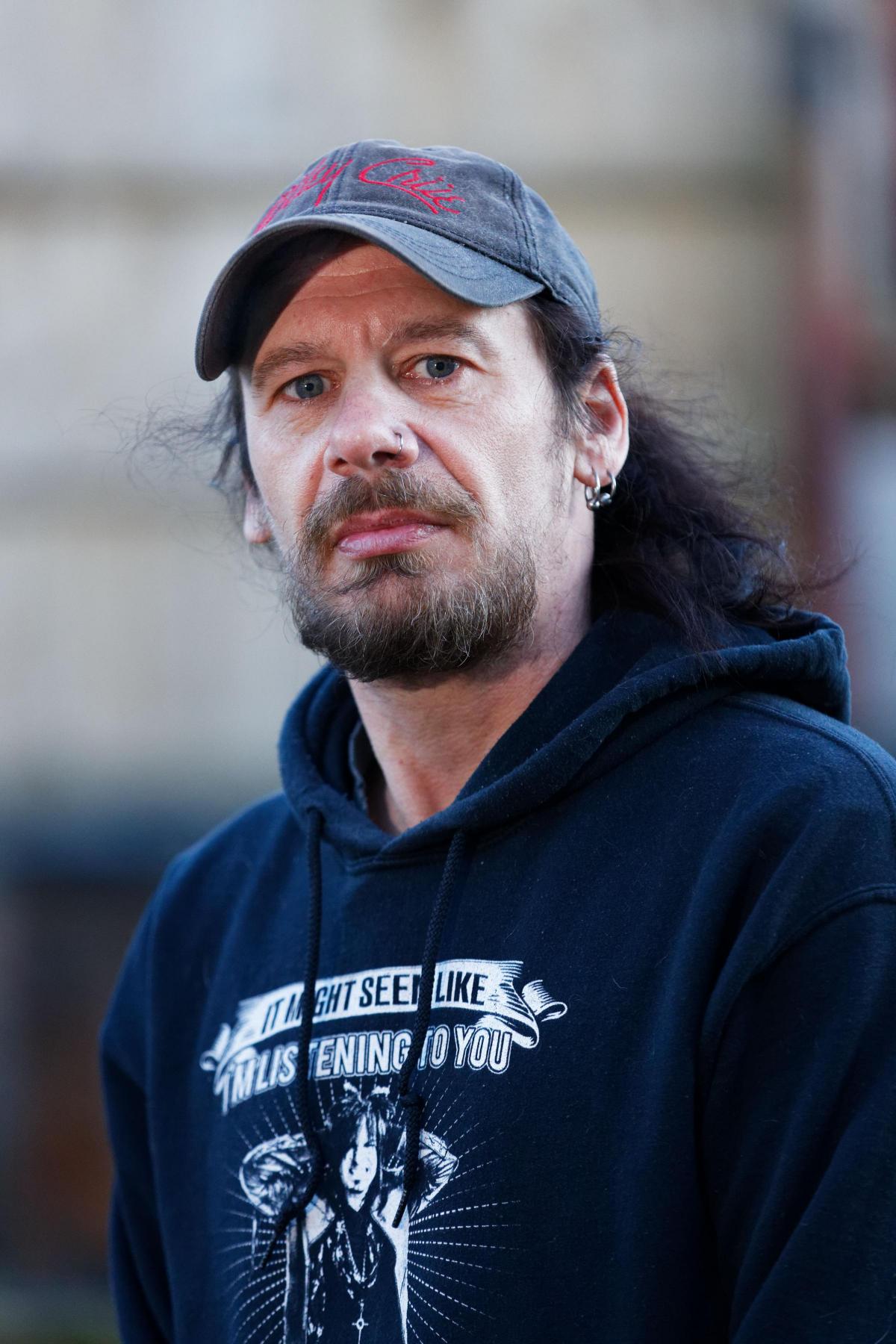

“I still lived with dad. I felt angry that he was taken from us so soon, having deteriorated so quickly. He was only reaching retirement age and had so much he wanted to achieve,” said Leigh Chilton.

“It wasn’t possible for dad to bring a claim during his lifetime, he was so unwell. So retrospectively seeking justice for him was important to me.

“I went initially to a solicitor in Liverpool, but after months of going back and forth they suddenly advised that they could not continue the claim in the absence of an in-life statement from dad, and no other witness evidence. By then, limitation had expired on the claim. I was shocked, exasperated, but still wanted closure for dad.”

Other solicitors recommended Hugh James, a law firm specialising in industrial disease cases. Though out of time, it took on and eventually settled the claim, to Mr Chilton’s “huge relief.”

“If I could offer advice to others who have lost loved ones to an asbestos-related disease, I would urge them to work directly with a specialist law firm,” he said.

“I learnt the hard way. Using a non-specialist solicitor at the start put the case in jeopardy. If I’d only known this before, things would have been so much easier at such a distressing time.”

Sarah James, an associate at Hugh James, said Graham Chilton may be among many Newport Forge workers who may have been exposed to asbestos. The company is no longer in business, so claims are pursued through insurers.

“Sadly, Leigh’s experience of losing his father to an asbestos-related disease is one we see all too often, especially in south Wales. It is important for people to seek specialist industrial disease legal advice,” she said.

“Through no fault of their own, workers and their families are still paying the price for employers historically not providing adequate workplace protection decades ago, and many may have been unwittingly exposed to asbestos.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel