While the church is, of course the special treasure of Bettws, the hamlet at the crossroad its interest.

Motorists who drive through, and even those who halt for refreshment at the inn are apt to miss a sight which takes us back in imagination to those days when the Norman conquerors were raising their strongpoints throughout our land.

Alongside the old road which runs almost due north from under Usk Castle we have still Norman mounds at Beech Hill one near Trostrey church, and many more beyond Bettws.

At the crossroads an excellent example comes into view, as in my sketch. Known locally as ‘the Brake.’ It is a tree-clad height rising to 318 feet, with the flat circular summit typical on such `mottes.’ The view from the top is impressive and shows how the artificially Usk crossing. raised hillock commanded not only the north-south road, but also the road from Raglan to the Usk crossing.

The Black Bear Inn at Bettws Newydd is a study in black and white. Its sign must be one of the best-known in the land, standing comparison with the ‘Monmouth Cap’ at the Llangua and the ‘White Hart’ at Caldicot. In spite of its well-cared for appearance the inn is at least 200 years old.

From the village I drove onto Clytha hill and a walk across a windswept hilltop field took me into the hilltop camp where all was calm. Now National Trust property (for Captain Geoffrey Crawshay presented it in 1945), Coed-y-bwnydd charms all visitors - except one, who, I understand, is repelled by some sinister influence which she encounters there. Maybe she is allergic to aristocracy, for the old Welsh name signifies ‘the wood of the gentry.’

In summer the undergrowth prevents exploration, but on this afternoon I could see how the fort had been planned, one trench only guarding the precipitous west and north-west, but two, three or four trenches on the other sides.

The shape was roughly oval, the entrance guarded by a tumulus, the circumference some 500 yards and the extent about eight acres.

I know few viewpoints more thrilling than the north-west edge of Coed-y-bwnyyd. On a clear day, Blorenge, the Black Mountains, Sugar Loaf, Skirrid and Graig are dramatic points on the skyline, the middle distance is green and pastoral, the fruit blossom forming white pools among the green, the brown churches and white farms peep out from among their trees, while our exquisite river steals out of Breconshire and meanders across towards us, takes a look at the Clytha hills, and then slips sweetly past Llanfair Kilgeddin and away.

When our friend Archdeacon Coxe saw the fort in 1800 he recorded that the tumulus at the eastern entrance appeared to have been fortified at each extremity with towers, of which the foundations were still visible.

He found many stones scattered on tops and sides of the ramparts, ;And concluded ‘The character is British, but the strait roads exhibiting vestiges of paved causeways diverging from it in all directions, favour a conjecture that it was once occupied by the Romans.’

Nigh the river, not the town, which is over six miles downstream, Llangattock is one of the churches dedicated to the saintly Cadoc, son of our own St. Gwynllyw (St. Woolos) From the barn I walked along ‘lavender lane’ until the cross of its ancient base.

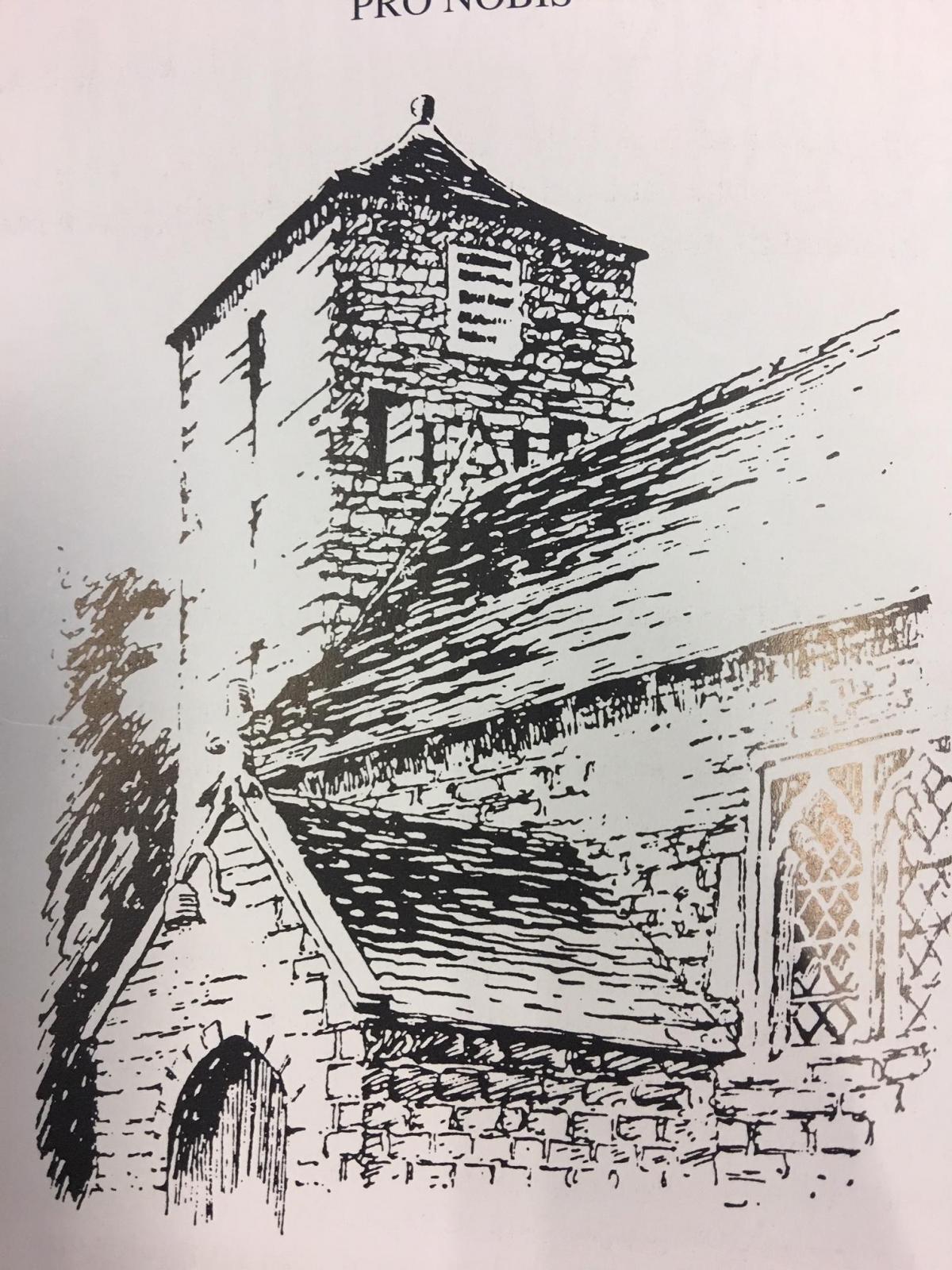

The church of Llangattock-nigh-Usk On my drawing of the church tower two large and two small niches are shown in the east wall. Two similar niches, also empty, are to been seen in the east wall of the church, and though unusual they may have held effigies of saints, all facing east.

Surrounded by daffodils, I studied the ancient building.

Bradney suggests that St. Cadoc’s was founded in the sixth or seventh century, and the present structure, stripped now of its ivy, bears a charming time-honoured appearance. Roof-marks on the east wall of the tower show that, of old, the roof of that nave was taller and had a steeper pitch.

In the churchyard, near the porch, I found the interesting tomb shown in the smaller sketch. the soul of the departed. At the head stands the ‘kneeling-stone,’ in which the knees would fit while prayers were made for the soul of the departed.

I cleared away much grass and turf to lay bare the inscriptions ‘vive U Vivas’(Live so that you may live) on the kneeling-stone, and on the flat stone recording the burial of John Howell of Llanwenarth in 1774, followed by the quatrain:

No life so long but

Sickness may at tenit

No life so strong but

Death at last will end it.

Within the church I noted the stairs and the doors which led once to the roof-loft but nothing now separates nave from chance!

The splendid little brass showing the lady with the sonorous christian name `Zirophaenzia’ hangs on the chancel wall. The memorial slabs - one showing the rector in 1644, a front view of head and body, but side views of his feet - are quaint, and the Norman font and Beauchamp titles (William Beaucamp was Lord of Abergavenny in 1392) should not be missed.

Close to the font is the massive slab known as the memorial stone of ‘David the Warrior.’ Though much worn, the interfaced cross, the axe and part of the inscription are still visible.

A century ago Mr Wakeman read the inscription as ‘David ap Ieuan Lloyd’: fifty years ago Bradney and Hobson Matthews gave the reading ‘David ap Hoell’: in good light I could decipher only the word “David” prefixed by a cross.

The stone dates probably from the mid-fifteenth century, in which David the Warrior would perhaps have been among the Welsh contingent at Banbury in 1459, fighting for the Yorkists.

In a glass case near the font is the greatly treasured Welsh bible - Y Bibl Cyssegr - printed in 1620.

It was the second edition of the translation made by Bishop William Morgan in 1588 and it is engaging to imagine Drake and his fellows chasing the Spaniards around our island

while the little Welsh bishop sat in his quiet room at Llandaff re-writing the bible in Eden’s language.

This copy was bought by the rector, the Rev Francis Lewis , for twenty shillings in 1769. From that date its story is not known until Mr William Hain his death in 1922 Mrs Haines presented it to the church. es of the Bryn bought it in 1889.

On Mr. Haines was a much loved man of Gwent. Deeply concerned in most county affairs, proud of his English and Welsh ancestry, and authority on his county’s history, he built up a unique collection of books on Monmouthshire and his library is now enshrined as the Haines Collection in the Borough library at Newport where it is in constant use by students and general readers.

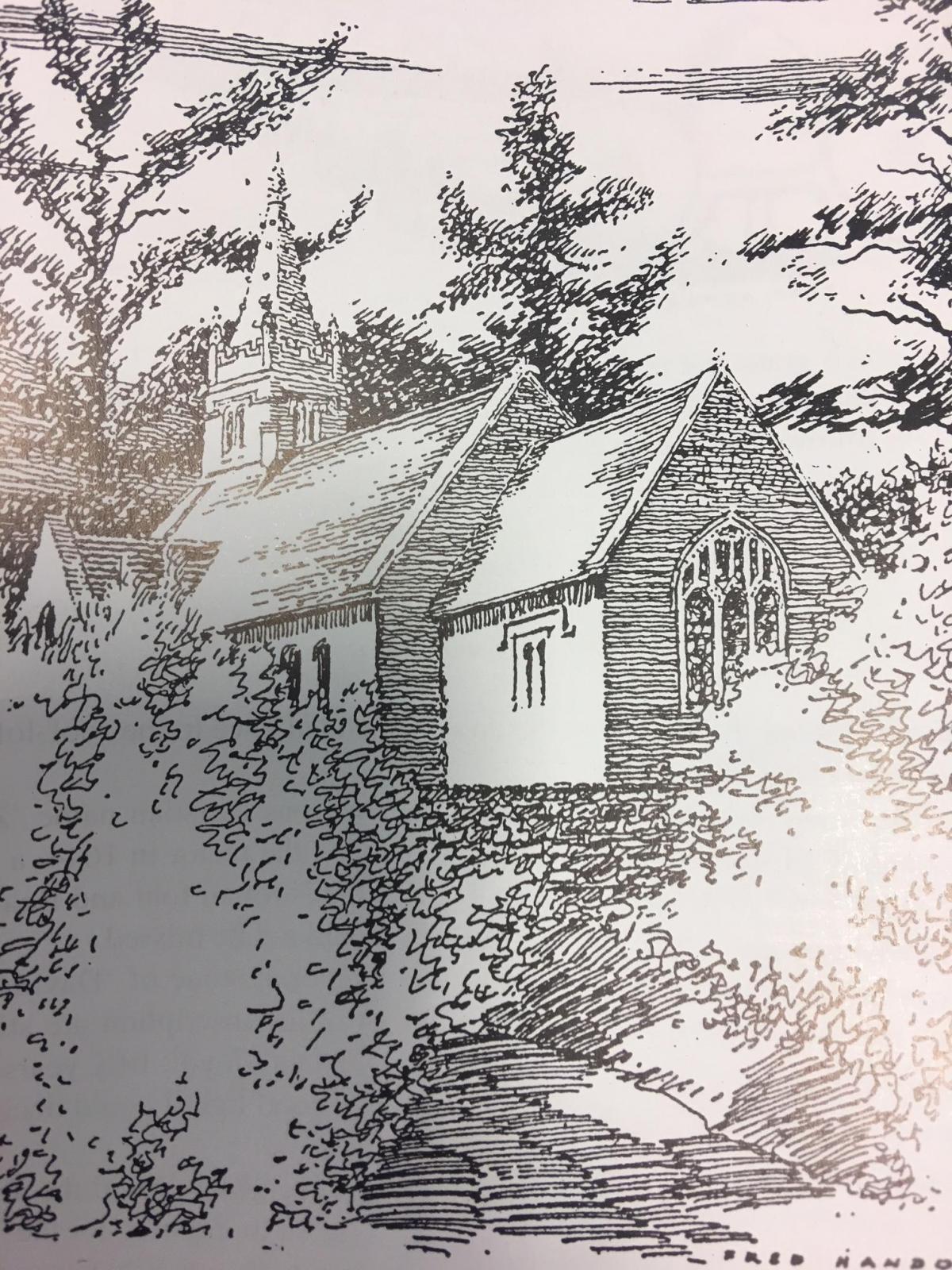

Beautiful as its name is the setting of the village of Llanelen. Dark, almost black, evergreen trees guard the church, the woods behind sleep in their robes of gold and russet, scarlet and apricot, and towering above all suave, silvery in the morning mist, the mountain stands as if in benediction. Memories of such beauty brought tears to the eyes and ache to the hearts, of Llanelen met exiled overseas in wartime.

l Courtesy of Chris Barber

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here