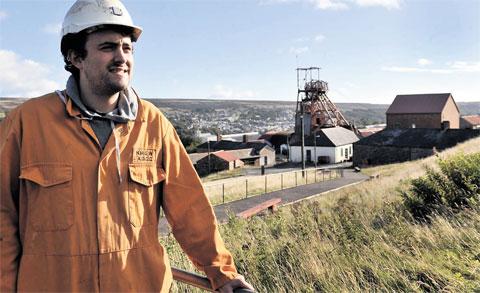

GETTING the low down on life at the Big Pit Big Pit is a big draw to the Gwent valleys attracting tens of thousands of visitors a year.

DAVID DEANS finds out what life is like above and under ground for the staff who work there. IT IS among Gwent’s bestknown tourist attractions, yet it is partially underground and run by staff who probably never thought they would ever work in a museum.

In the years since it was opened as a museum in 1983, Big Pit in Blaenavon has opened up a proud part of the heritage of the Valleys to people from across the world.

In 2011 more than 130,000 people visited the underground part of the attraction in the former working Big Pit mine – guided by former miners from the South Wales coalfield.

Of the 62 people that work at Big Pit, 38 are former colliers.

I was given a glimpse of what is is like for those who guide visitors and keep this popular venue ticking over.

It was a cold Friday morning when photographer Becky Matthews and I arrived at the Blaenavon venue while workers were doing the first jobs of the day.

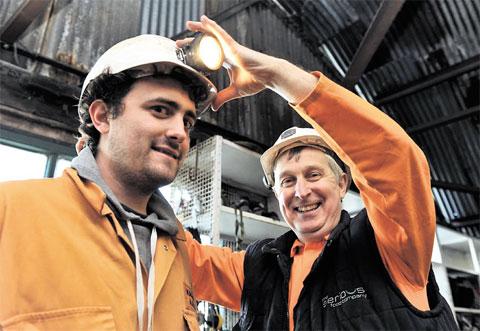

Before I knew it I had donned the familiar white helmet and orange overalls – originally brought in for miners during the 1980s – and was helping to prepare the helmet lamps that will be worn by visitors to the preserved mine.

Each lamp is prepared for dispatch with a battery and a selfrescuer, which are used to help a person breathe in case of a fire.

There we met Robert Wertheim from Ebbw Vale, an ex-miner who worked at Marine Colliery.

Mr Wertheim said he started at working at the museum after having worked at a factory: “It’s not like a job. We’ve met people from everywhere, New Zealand, Japan. You meet some celebrities when they come through.”

Paul Green, deputy manager at the museum, then took us around to the visitor entrance to the shaft, where a cage – not a lift, it was emphasised – lowers people into the preserved mine.

The public travel down the 300 feet shaft at seven feet a second but staff from the museum go down through the shaft at one foot a second to check its condition in the mornings.

The process is controlled from a cabin where a winder driver raises and lowers the cages that bring people in and out of the mine.

The winder itself was built in Newport in 1951. On the day we attended it was being driven by Paul Willis, a winder driver from Tredegar who used to work at a pit in Oakdale until it shut. He had started work at the museum in 2001, but also said he had worked at a factory prior to coming to Big Pit.

While Big Pit has a crew of maintenance staff, such as fitters and electricians and people that repair the mine itself, they can also show visitors around and act as guides when needed.

Our photographer, unable to come into the mine, then left me to my own devices and I went down into the bowels of the Big Pit.

During this time of the year many of the visitors are school parties. I joined a group of GCSE students from Hereford, who were themselves doing a project on the mine.

Our guide was Peter Harding, from Pontlottyn, Rhymney Valley. The start of the tour now seemed familiar to me – having been down here three times in the past with friends and family – and everyone was asked for any contraband such as cigarettes, lighters and tobacco before we entered the mine.

Mr Harding, and several of the rest of the guides, picked up on my notepad – which as usual was filled with shorthand notes I had made on my journey around the site.

The guide asked memyname.

“David,” I said. Insisting on calling me Dai, he later granted me a nickname – Dai Shorthand.

As it happened, the bus driver on the school tour was also called David, who our guide called Dai Last Man and gave the important task of shutting doors behind us to control the air flow. Mr Harding, whose tabard was lined with badges including some given to him by visitors like the president of the San Marino Football Association, tells us that the mine, which was first opened in 1880, predominantly produced steam coal.

He informed the youngsters, aged 15 to 16, if they have lived in Blaenavon in the 19th Century they would have likely worked in the mines.

Despite its purpose as a tourist attraction the mine remains a complex of shallow, winding tunnels. Most people over a certain height will spend much of their visit ducking the ceiling – with the helmets coming in useful on more than a few occasions.

At one point, Mr Harding stops us by a door and asks us to switch off our lamps. One by one the visitors oblige, and are plunged into total, absolute darkness. With no source of lighting, natural or man-made, the group can literally not see their own fingers in front of their faces.

Mr Harding said one of the first things you do is tailor the tour to the people. He may, for example, make the tour more basic if there are a number of international visitors.

Not all that come to Big Pit want to go underground, and that’s where the gallery comes in. Itself built into the hillside of the site, the gallery offers a simulation of the underground environment and gives visitors a chance to look at some of the processes used to extract coal.

Currently the guides and maintenance staff are ex-miners, but Andrew Williams, who was working at the Gallery when we visited, tells us that the museum has brought in two apprentices in their 20s, who are to be trained as guides.

● Families with children can come along to Big Pit this halfterm to take part in the venue’s Tip Top Recycled Art event.

The event is from October 29 to November 2 from 11am to 4pm. It costs £1 per child.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here