A FORTNIGHT after the Conservatives' shock win at the General Election and there are still those who do not want to accept the will of the people.

I have voted in several general elections when the party for which I voted did not win power. It might even have happened this time. Then again, it might not - you'll never know and that's the whole point of a secret ballot.

But I've never felt the need to protest about the result of an election. You can't always get what you want, as someone who apparently predicted the election result once sang.

Yet protests there have been pretty much since David Cameron's slim majority was confirmed.

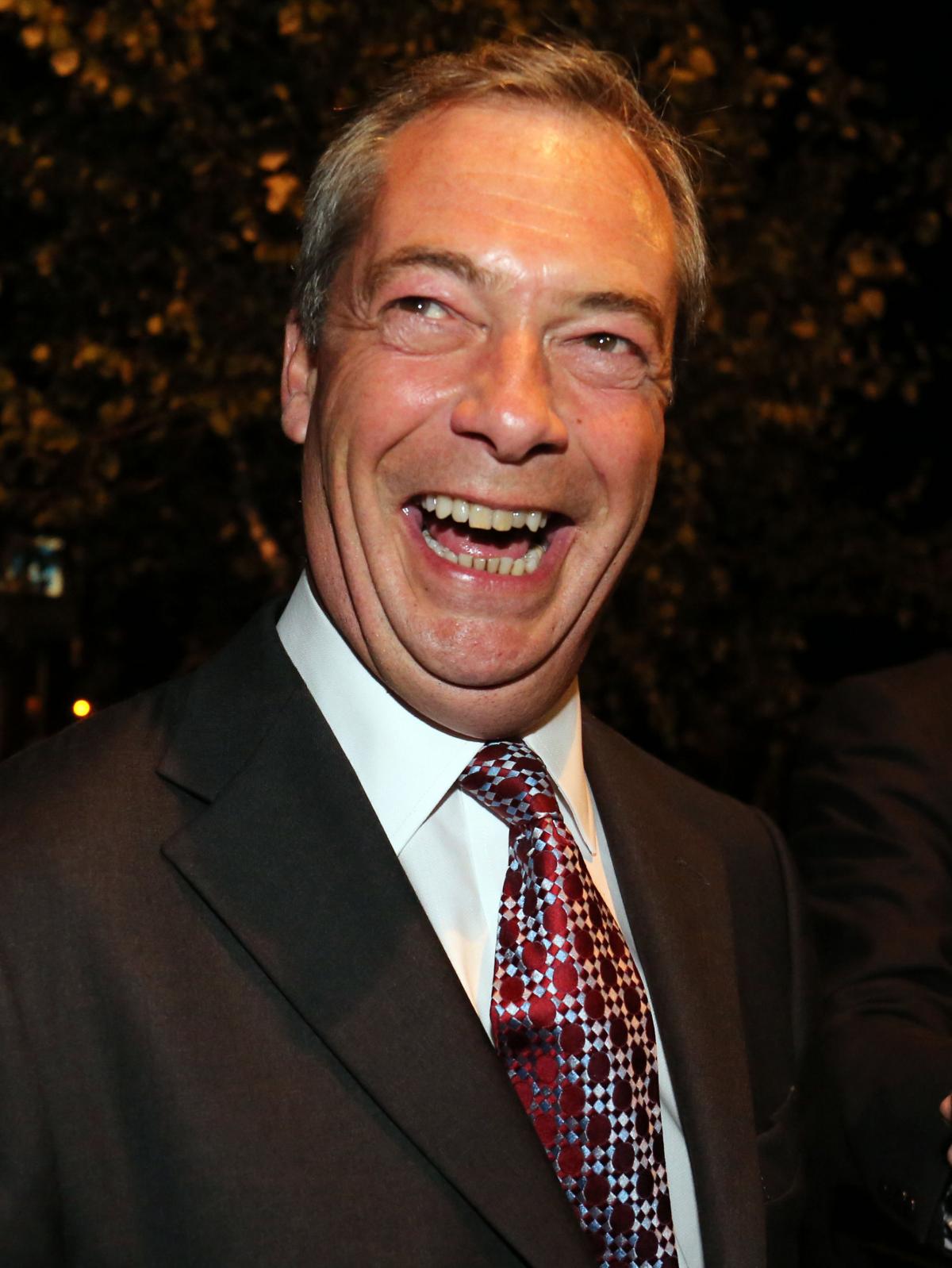

So you have Charlotte 'mad as hell' Church leading marches through Cardiff and Nigel Farage calling for proportional representation.

There is a certain irony in millionaires railing against austerity and the most anti-European party calling for the most European voting system.

On the face of it, there is an undoubted unfairness that a party (the Tories) can gain just 37 per cent of the votes cast while winning more than half of the available seats, while another (Ukip) can come third in the share of the vote with more than 12 per cent but win just one seat, and another (SNP) gains less than five per cent of the votes but wins more than 50 seats.

But every candidate and every party entered the election campaign knowing the rules. Britain operates a first-past-the-post system.

The nation was given the chance to move to a form of PR in 2011 and the electorate voted overwhelmingly to retain the current system.

That's how democracy works.

Those now protesting about the result of the election resemble a bunch of stroppy teenagers wailing 'But it's soooo unfair!' because they haven't got what they want.

Those so opposed to a Conservative government would be better advised to lick their wounds, work out why the result went against them, and then redouble their efforts to ensure they kick out Cameron and company in 2020.

For some parties, that is easier said than done.

The Liberal Democrats face a desperate time in the months and years ahead. Virtually destroyed as a parliamentary party, they face a huge task if they are ever to emerge from the political wilderness.

Labour faces a period of internal reflection and revolution unseen since Neil Kinnock worked tirelessly to make the party electable in the late Eighties and early Nineties.

As with John Major's unlikely defeat of Mr Kinnock in 1992, Labour simply did not see this result coming until the very last moment.

Their next choice of leader (sadly Chuka Umunna, the best candidate in my view, is already out of the race) is crucial.

Britain is a better place when it has an effective opposition and a potential alternative government in place.

That will be the challenge for the next Labour leader - to hold the government to account while making their party electable again.

Whoever that person is may find themselves cast in the Kinnock role, doing all the hard work in reforming the party only to see their successor reap the rewards at the polls. A certain David Miliband might just be the Tony Blair character in that scenario.

Much of Labour's problem at this election was the complete abandonment of the Blairite principles that won the party three successive elections at the turn of the century.

Ed Miliband was right to label Iraq as a mistake that should not have been made. It will always remain the defining black mark against Mr Blair's 10 years in office, despite the former prime minister's defiance.

But to ditch the New Labour project wholesale was simply throwing the baby out with the bath water.

You do not have to be an expert in political history to see that the further Labour moves to the left (Foot, Miliband), the fewer people vote for the party. The closer it moves to the centre (Blair), the more the reverse happens.

The trick the next Labour leader will have to pull off will be to find a place in a crowded political centreground where their voice can still be differentiated from other parties.

In the meantime, we have the government who won the election fair and square under a system the electorate preferred.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel