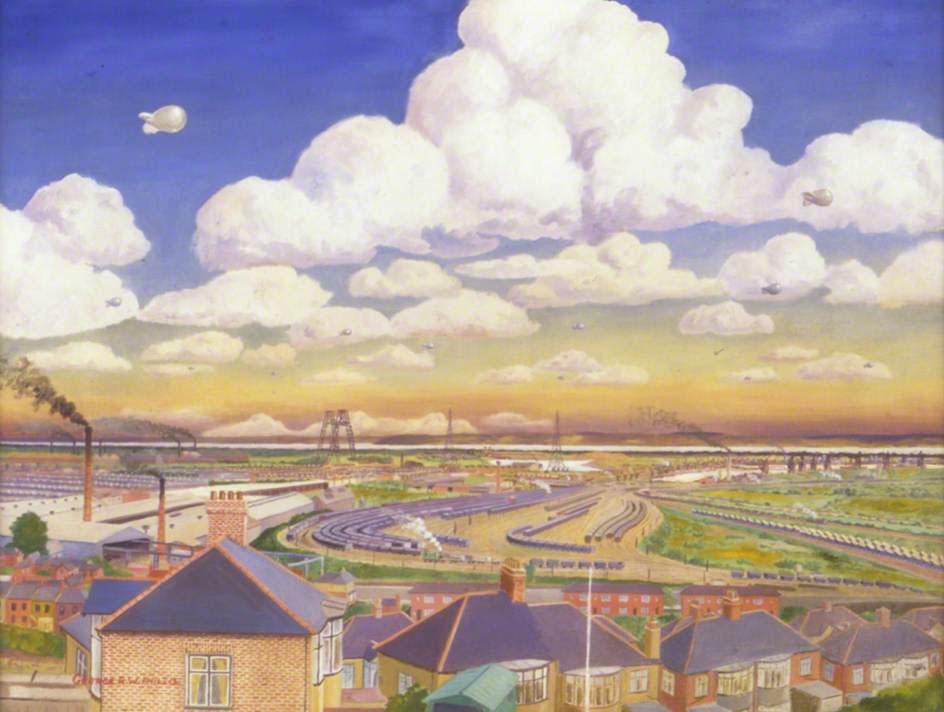

A PAINTING in the Newport Museum and Art Gallery depicts a summer scene looking out over the rooftops of the Gaer towards the docks and the Transporter Bridge. The cheery picture looks like a scene from 50 years ago. But above the scenes of industry the sky is filled with balloons.

Barrage balloons were used to defend the town's railway marshalling yards and docks where goods vital to the war effort were shipped.

The picture, called simply ‘Balloon Barrage, Newport’ by George Robert William Phillis is an eloquent depiction of how Newport looked at this stage in the war.

The oil on canvas work shows a peaceful looking Newport, with the benign 'silver-grey elephants' looming protectively above the town. The ferocity of war seems a world away. The painting gives an idea of just how Newport was protected and how German bombers descended to unleash their bombs at their peril.

Barrage balloons became a common sight in the skies over towns and cities during the war and Newport relied on them heavily to protect its docks and marshalling yards.

Newport was defended by 966 Squadron of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. Based at Tredegar House, the unit had only been in Newport for three weeks when it had its first success when one if its balloons brought down a German Heinkel bomber. It was a success with a tragic end as the aircraft ploughed into a house on Stow Park Avenue, killing two children.

The squadron had smaller units elsewhere in the city such as Belle Vue Park. Naomi Screen, 81, lived on Waterloo Road during the war. She remembers the barrage balloon men well.

"I remember the RAF coming to the park. They built a hut where they were based. We used to peer through the railings at them and they'd say 'hello'. My father used to chat to them."

She recalls the size of the equipment tethering the great gas bags to the earth. "They built a holder for the cable in the park. The lines holding the balloon were about an inch thick."

She remembers very well the fateful night when Newport's barrage balloons claimed their first victim. "September 30th was my seventh birthday, so I was still just six years old" she recalls.

"We were sleeping downstairs and we heard a loud bang. A door fell in and hit my father on the head, cutting him. We had beautiful leaded windows which were all smashed. My sister's arms were cut by the flying glass. Some of our ceilings collapsed."

Peter Garwood of Trellech in Monmouthshire has done much research on the role played by barrage balloons during the war.

“Barrage balloons were a hugely important part of the defence of the Britain from aerial attack during the war.” However he says that importance didn’t always come from their use in downing German bombers. “Although the unit based at Newport scored a notable success, barrage balloons actually brought down more British aircraft by accident than German. Their value lay in deterring the enemy from flying lower over targets and thereby dropping their bombs more accurately.”

The success of Newport-based 966 Squadron was widely trumpeted. “As the first balloon unit to bring down an enemy aircraft they were feted and sent to talk to other balloon squadrons, especially in South Wales” Peter says.

One member of the squadron whose ease in front of an audience would have made him the ideal choice to give such pep talks was someone who would find fame in the showbusiness world, but then was officer in charge of administration for 966 Sqn at Newport.

Flight Lieutenant Charles Kenneth Horne would later, as plain Kenneth Horne, become the eponymous star of the radio series ‘Round The Horne’ through the Second World War and after.

He made his broadcast debut just over a year after the Heinkel was downed. In early 1942 a BBC producer asked whether the RAF station at which Horne was based could put on an edition of his programme, the quiz for anti-aircraft and barrage balloon stations called 'Ack-Ack, Beer-Beer' (named after the RAF abbreviation for the units). Horne duly compered the show and his time in the RAF would inspire one of his most famous creations, the radio comedy set in a remote and fictitious Royal Air Force station, Much-Binding-in-the-Marsh.

Successes like that enjoyed by 966 Sqn were few and far between. In their day-to-day operation the balloons could be difficult to handle and at times, lethal.

Balloon operator Jean Shepherd served across the Bristol Channel guarding Avonmouth Docks. She recalled how the life of the Balloon Operator or 'Bal/Op’ was "rough, tough and at times dangerous". The flights were usually small units, like the one that existed at Belle Vue Park.

She remembers how each site would have gravel circle with a pit in the centre in which wire stays were attached to secure the balloon on the ground. “they were anchored by several one-hundredweight (50kg) concrete blocks and these had to be shifted as the wind changed.”

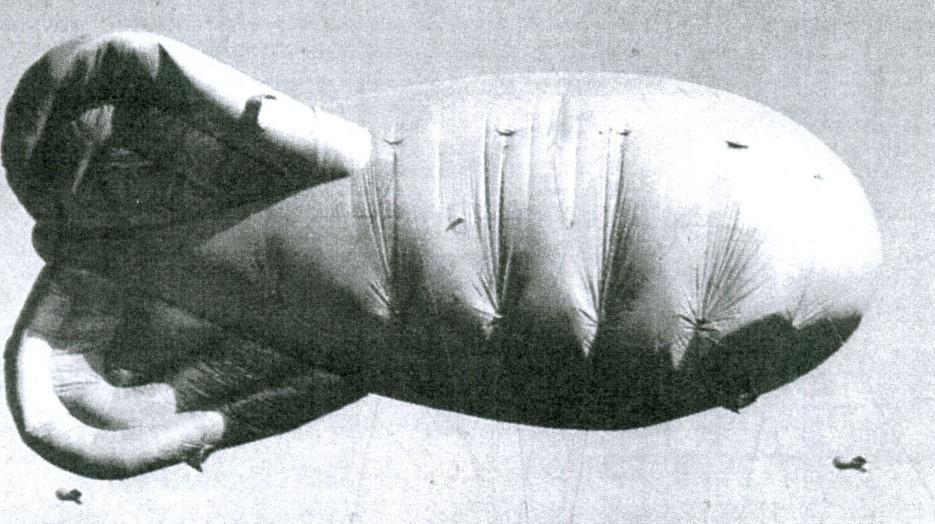

A Ford V8 engine mounted on a truck was used to power the winch which raised and lowered the balloon. The last few hundred feet of the inch-thick cable were painted red as a warning of how lethal this seemingly docile weapon could be. If the cable was let out too far, there was a danger of the balloon coming loose, which would unleash the metal cable with a power that could easily decapitate a man.

Members of the flight took turns in guarding the sites armed with truncheons and torches.

There were other risks too. The cables tethering the barrage balloons were later fitted with explosive charges which would fire when they were struck by an aircraft. The resulting tension would cause the cartridges to fire, severing the cable in two places.

A parachute would open at one end of the cable which would be dragged along by the aircraft, hopefully causing it to crash. The other parachute would pull on the balloon causing it to deflate. Often the charges misfired and the balloons would drift until they could float no more. There were reports of 'rogue' balloons killing people on the ground as they landed.

These problems aside, their effect was seen by a Ministry of Information pamphlet of the time which saw how the balloons had made: “a positive contribution to the safety of our cities, ports, dockyards and factories, and the fact that our industrial effort has remained so largely unimpaired is in no small measure due to the dogged maintenance of this form of passive defence.”

The balloons stood guard over our towns and cities until the threat of German bombers subsided later in the war. They still performed vital work over the South East of England as flying bombs rained down, but in Newport their job was done and no more would these silent sentinels watch over us.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here