INSTANTLY recognisable in their red tunics and bearskins, the Welsh Guards celebrate their hundredth anniversary this year, receiving the freedom of Newport among other honours. But they had their baptism of fire 100 years ago only months after being formed in a battle which saw men kick rugby balls as the signal to attack.

THE regiment had only been in existence for eight months, but the Welsh Guards were thrust into one of the First World War's bloodiest battles.

The regiment was created on 26 February 1915 from soldiers with a Welsh background serving in the other Guards regiments. It mounted its first guard at Buckingham Palace on St David's Day three days later.

By 1 August they had sailed for France to join the Guards Division with whom they would fight in the Battle of Loos.

The battle was one of firsts. It was the first British 'Big Push' of the war where tens of thousands of men were deployed at once. It was the first time that Lord Kitchener's army, the New Army was used. Britain's professional soldiery had all been wiped out in the battles of the first year of the war and now the thousands of men who had responded to Kitchener's famous words that 'You're country needs you' were braced for action. It was also the first time that Britain used poison gas.

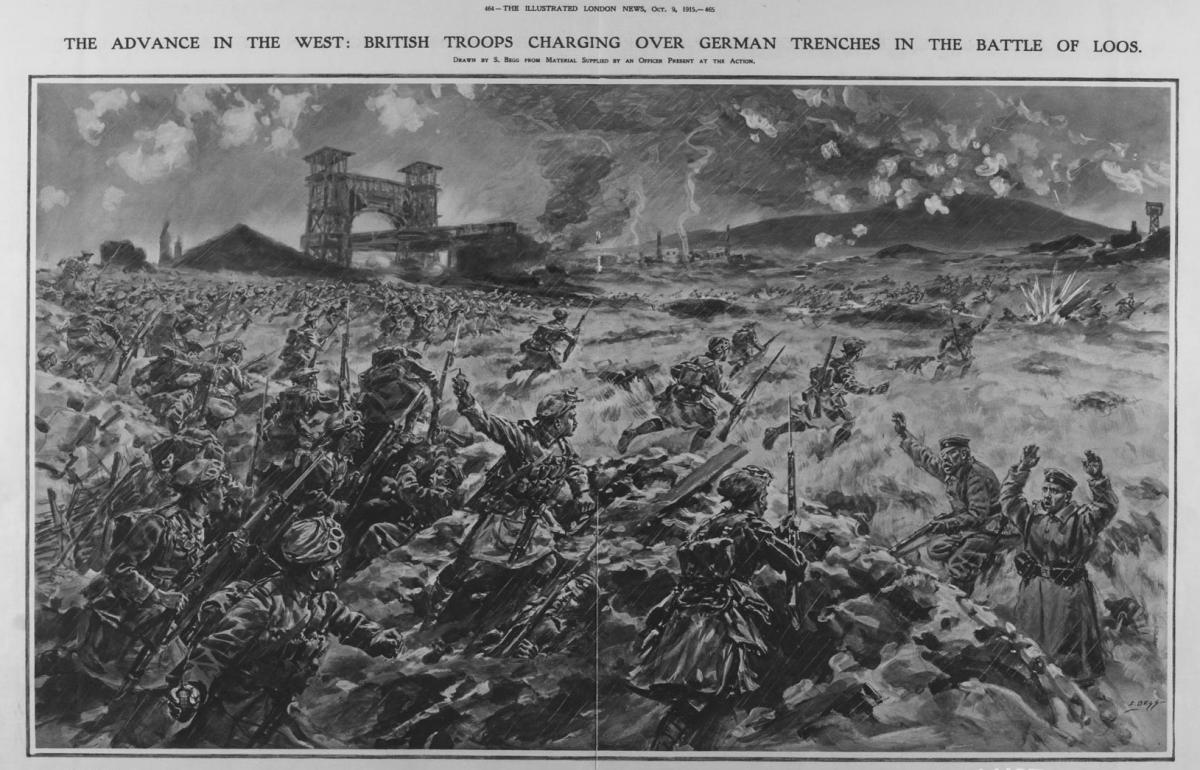

Yet it was also the end of one way of waging war. The battle contrasted with the usual image of First World War carnage. It was fought without the colossal artillery bombardments like that used at the Somme which turned battlefields into hellish shell-marked moonscapes. The British ‘Tommies’, who had yet to be issued with steel helmets, fought this battle in cloth field caps and largely with rifle and bayonet.

The Welsh Guards, alongside the other Guards regiments were tasked with taking the so-called ‘Hill 70’ on September 25th. This small hill would give the victor mastery over the area and so was a vital target. Due to the convex shape of the slope, the Guards were out of sight of the Germans for the first few hours of the attack when they set off at 6pm as dusk fell. But on rounding the top of this slope, they were raked with murderous machine fire.

One guardsman remembered the moment they came under fire: "I didn't understand it was fire! It was like a lot of whips cracking. Then the order came to get into artillery formation, which is about ten feet between each soldier, and we went down in line like that, straight down the hillside, and it was a most eerie affair because it sounded like whips cracking, and then you'd see the man on your left, just flop down and that was that."

Another observed coolly: "As a matter of fact, I was a bit disappointed with the first two shells. I thought they'd make a bigger explosion. But I found out afterwards it wasn't always the ones that made the most explosion that caused the most damage."

By 11pm they were ordered to withdrawal 100 metres to a position that could be defended in daylight.

The Guards were not the only Welsh soldiers in action that day. A soldier with the Welsh Fusiliers recalled how the battle began: "We kicked off with a rugby football...chaps with half a dozen rugby balls belted them over and in we went."

Despite the spirit with which they went into action, they were scythed down too by the machine gun fire. He tells of officers carrying their swords into battle: "They didn't even get to the top of the trench before they were hit by the machine gun. They had their swords flashing and the Germans saw it and they were looking for officers."

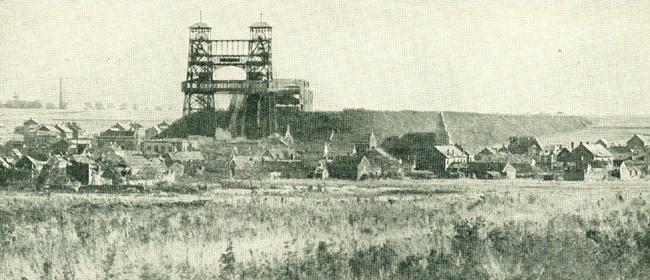

The area around Loos would have seemed familiar to many of the Welshmen as it was one of France’s richest coal mining regions and dotted with mining villages. A striking landmark was the so-called ‘Tower Bridge‘, a massive pit head lift which stood near the village of Loos and was so-called as it reminded those who saw it of the original Tower Bridge in London.

The Germans had used it as an observation post and after the British took the village they did the same until it was eventually destroyed by enemy fire.

The Argus reported at the time of battles fought in "that mining country, with its tangle of pit-heads and slag heaps and railways."

Much hope was invested in the use of gas. The British knew that the Germans had little protection against it. There were no reservations about its use after the Germans had deployed it against French and Canadian troops at Ypres earlier in the year.

The plan called for the release of 5,100 cylinders of chlorine gas (140 tonnes) from the British lines.

The British soldiers had been issued with a primitive gas mask called the P Helmet, a hood-like device, which at least was an improvement on the protection used at Ypres. Here soldiers soaked handkerchiefs in urine and held them to their faces.

However, the gas was to have disastrous results for the British. As they released the gas it blew back on the attacking troops, causing more damage to British than the enemy. The British suffered around 2,500 gas casualties, although only seven actually died.

An officer told of clouds of gas blowing towards the British positions. "We had to tuck our helmets in all the tighter. I was wearing two helmets one over the other, but in spite of this my throat became sore."

When reports of the battle appeared in the Argus, they carried the warning from British commander Sir John French saying: "The Battle of Loos is likely to rank high in the story of the war."

In the Argus of September 29th, he said the fighting around Loos was "severe" and that the British held all the ground “north of Hill 70 which the enemy retook on the 26th, but we have also made further progress to the south of Loos."

Reports became bolder with news the next day of the "glorious rush that carried Hill 70".

But by October 9th the Argus was reporting "violent fighting" at Loos, adding the British had repulsed German attacks but with "heavy losses".

By the 10th, the capture of Hill 70 was being described as "the limit mark in our great offensive." Additional gains of between 500 and 1,000 yards were told of in an "excellent" report from Sir John French.

The Germans had some success at re-taking ground the British had won. By mid-October, British counter-attacks had fizzled out.

The British lost 59,247 in the campaign out of 285,107 total casualties on the Western Front in 1915.

Among the dead were two Welsh Guards from Gwent - one killed at the beginning and one at the end of this costly campaign. Private Frederick Clarke of the 1st Battalion died on the 27th September he lived on Durham Road, Newport. Private Albert Day, also of the 1st Battalion, was born in Abergavenny and lived on 8 Regent Place in Llanhilleth with his wife Livinia Ann. He died on 12 October.

The name of Loos was then the first battle honour to be won by the young regiment and many more names would follow.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here