THEY were the bold sailors who guided ships into Newport Docks – and stood to make a handsome profit if they did it well. Martin Wade tells the story of the Newport pilots and one of their ships, the Mascotte, which survives.

The Bristol Channel with its volatile weather and tides was no place for a faint-heart. Pilots had to venture out when others would stay safe in port. "Bad weather is our chance" they'd say, "That's when ships want pilots the most".

The pilot's job is one of the oldest in seafaring. They are the guides for ships entering port, shepherding their charges around unfamiliar sandbanks, currents and tides. Often local fishermen, they would supplement their income with piloting charges and sail out in their fishing boats to catch passing trade. These heavy working boats though were not the most swift or agile of craft and a specialist design evolved.

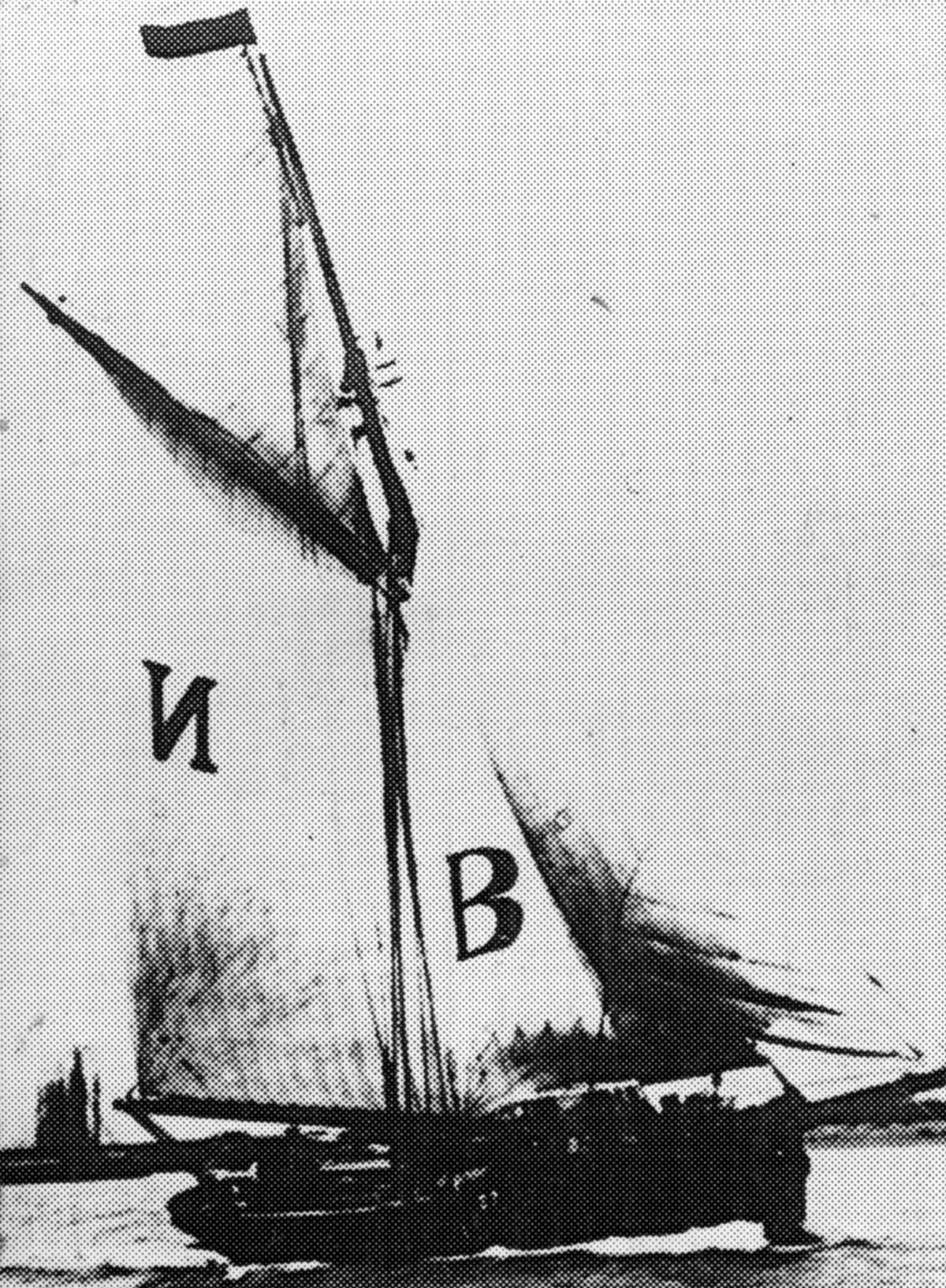

The Pilot Cutter was built to make sure the guide could reach incoming ships easily and ply for the lucrative trade in helping them to port. The boats had to be fast and manoeuvrable. They had to be able both to compete with other pilots in the race to meet likely trade and deal with the kinds of weather that would deter other ships from putting to sea. They also had to easily controllable. When coming alongside a cargo ship in a rough sea, the crew had to be confident they could manoeuvre safely to allow the pilot to board his customer's ship.

The Bristol Channel Cutter refined this design even further. It had to deal with the exacting challenges of the channel and the Severn Estuary. Having the second-highest tidal range in the world, the channel has challenging seas aplenty. The strong tides, winds, sand bars, currents and coastline of the Bristol Channel meant the design had to be that much more nimble and the Mascotte is a prime example of this.

The late 19th Century was a good time to be earning a living as a pilot in these waters. A pilot on the Bristol Channel in 1887 was earning an average of £324 per year, with some earning as much as £1000. A ship guided from near Barry to Newport or Bristol could pay £46.14s for the privilege. A similar distance journey into Liverpool from Llandudno would cost £14.9s

The Newport pilots came in different types, depending on their approach. The 'cinchers' would service trade from the harbour mouth and as they didn't have far to go, could sleep in their own beds. The 'Crack of Dawn Boys' would moor in Barry and slip out early to catch any trade that was not wanted further down the channel. Most others would go further down the Estuary to steal a march on those staying further east, while the boldest were the 'Western-going' pilots who would range as far as the English Channel in search of trade.

Very much a 'Western-going' pilot, Newport pilot Thomas Cox, had the Mascotte built in 1904.

The Newport-built vessel was a graceful, yet muscular member of the breed. At 60 feet, she was ten feet longer than most pilot cutters. Built to traditional lines with the hull made of larch planks fixed to an on oak frame and deck made of Douglas fir, she is a sinuous fusion of wood and craft on water.

As well as being longer, she was twice as heavy as other cutters. This extra bulk made her more capable and more profitable. The Mascotte could sail longer to find a ship that would bring profit. She once sailed around Land’s End and then to Dover to meet a ship from London bound for Newport.

Thomas' father Charles Cox, was a Bristol pilot who moved his business to Newport when the docks opened and all five of his sons followed him into piloting. These brothers competed with each other and other pilots for the lucrative trade. It seems there was little love lost between Thomas and his brother, Elijah in particular. The pair were reported for fighting on the quayside in Newport, a matter which was taken up by the harbour commissioners. The pilots would work into old age, still finding the energy to take on the squalls of the Severn Estuary. Thomas and Elijah themselves were 63 and 71-years-old when this brawl took place.

A Captain Bartlett, pilot manager at Newport, described the Mascotte as “perhaps the most outstanding boat in Newport ... She looked a very capable boat although I never saw her pressed very hard. But I think this was due to the temperament of the Pilot rather than to any fault of the boat.”

But the trade was not without its risks. Mascotte started work in April 1904, but by June, when she was sailing off Lynmouth in the Bristol Channel, disaster struck. Thomas Cox described how in fierce weather, the mainmast was blown away with the topmast, masthead, gaff topsail, jib and mainsail also torn from the vessel. Some of the gear was saved, but she had to be towed to Newport, which cost £20. Cox’s frustration could be imagined as the ship sat idle, costing him money.

She worked for 11 years until 1915 when steam-power finally put paid to sail-driven cutters.

By then aged 72, the retired Thomas Cox, sold Mascotte to Thomas H. Michell of Cornwall, grandson of the biggest mine owner in the county. She passed from one owner to another, with a spell being laid up in the Second World War and narrowly avoiding being broken up in the 1950s.

She was taken by a succession of owners, including one her brought her back home. Newport saw her graceful lines again in June, 1987 when Mascotte entered the docks for the first time since 1915.

Later, she was bought by Cardiff brewers, Brains in 1991 with a view to mooring her outside a pub. Thankfully, this plan was shelved as the Mascotte’s keel was too deep for the site, so once more she was sold. Now she is in full sailing fettle again and fitted with a stylish cabin and accommodation and takes passengers around the Western Isles of Scotland.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel