Twenty years ago one of the biggest engineering project Wales has ever seen was completed in a corner of Gwent. It is used by tens of thousands of people every day and is a vital part of our transport network. MARTIN WADE looks at how the Second Severn Crossing was built.

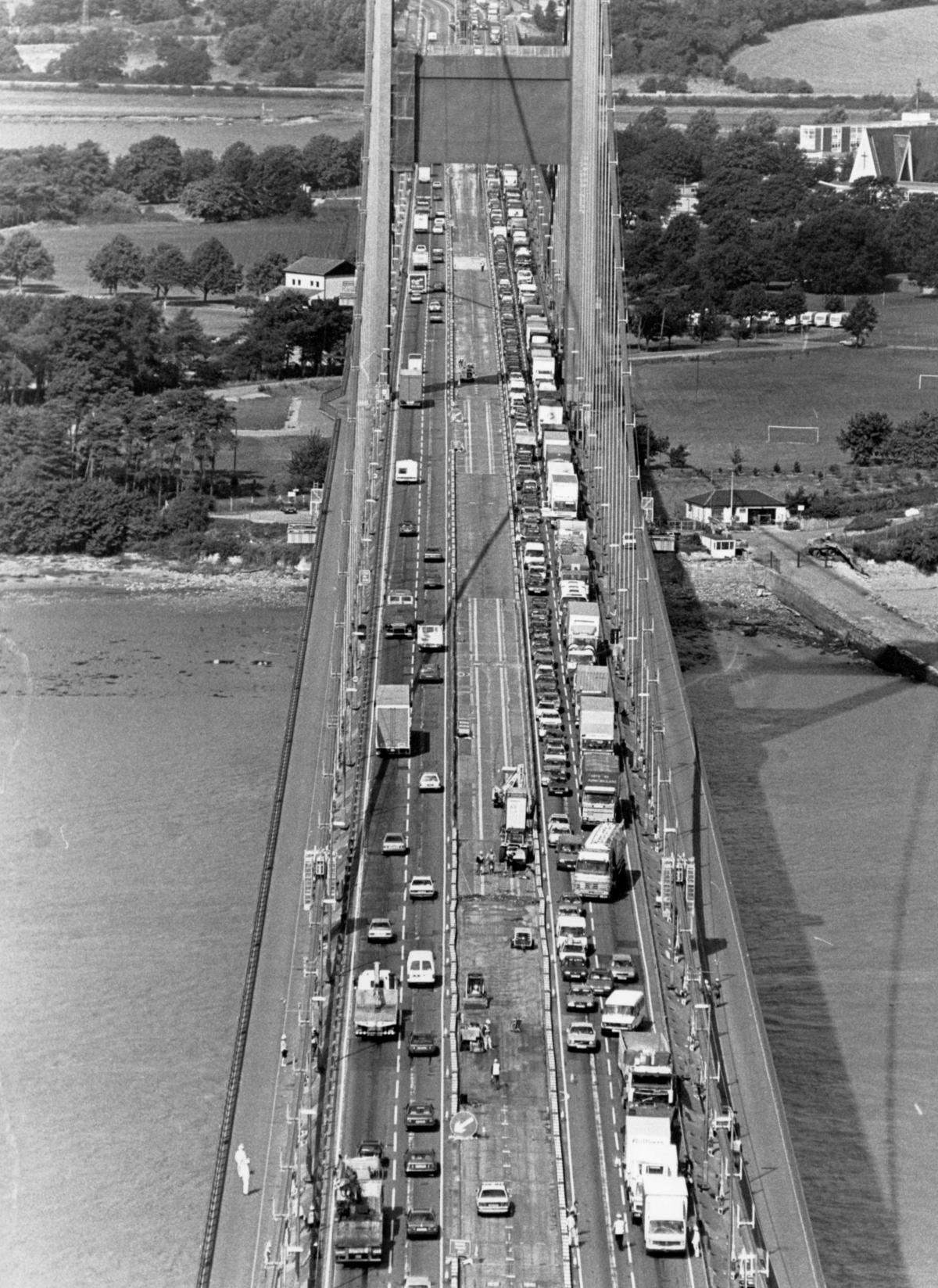

BY 1984 traffic across the first Severn Bridge had tripled and it was projected that by the mid-1990s the old bridge would be running at capacity. Between 1980 and 1990 traffic flows increased by 63 per cent with severe congestion in the summer and at peak rush hour. This was made worse by high winds, accidents and breakdowns. Clearly something had to be done.

Experts warned if a second road crossing wasn't built, congestion would build on the M4 and M5 and spread to the local road network.

The government first started looking at building the crossing in 1984. Although early plans included a tunnel, in 1986 it was decided the new crossing would be a bridge to be built five kilometres downstream of the existing Severn Bridge.

The crossing would span the estuary from the Gwent shore south east of Caldicot to the Avon shore near Severn Beach, itself a distance of five kilometres.

An agreement was signed between the Government and Severn River Crossing Plc in October 1990 and work began in 1992.

The crossing would be made up of two viaducts connecting the bridge to the Gwent and Avon sides. In the middle of the estuary these would be linked by a cable-stayed bridge 912 metres long over the deep water channel known as the Shoots.

The main span of the bridge was to be more than 37 metres above the highest tide level.

In Gwent, an approach road was to run westwards from the bridge, connecting with the existing M4 between Rogiet and Undy.

The first Severn Bridge has long suffered from the effects of high winds, with the bridge having to be closed of traffic restricted. A three-metres high wind shielding was added on the Second Crossing to ensure traffic could still flow in strong winds.

Strong, variable currents and a massive tidal range meant the bridge's foundations had to be built at a specially constructed site on the Welsh side near where the bridge started.

The 37 piers supporting the bridge were built on the site. These completed 'caissons' or hollow concrete shells were raised on hydraulic jacks to allow crawlers underneath. Similar to the powerful vehicles which transported the Space Shuttle to its launching pad, they would slowly take the 2,000 tonne monoliths to the water's edge to be loaded onto the barge called 'SAR3'.

At high tide the barge would be positioned by laser-beam over its precise location on the estuary bed.

The crane on a special barge 'Lisa A', which had legs to enable it to be jacked up above the water level would then lower the caisson into position at low tide. The hollow structures would then be filled with concrete.

The sections for the deck were made from steel with a reinforced concrete roadway.

The pieces, each 3.6 metres wide and 200 tonnes apiece, were floated out on SAR3 and hoisted into position, bolted on to the neighbouring plate and cables attached to the two tall pylons. The needle-like cables reaching from tall pylons held the plates in place. As they were pieced together, the bridge’s distinctive ‘S’ curve began to take shape.

There were concerns over the project. The Gwent Levels were said at the time to support 115 rare species, some of which were unique to the Levels. Construction firm Laing enlisted environmental consultants to monitor the building work's impact on the area.

Others feared how the level of traffic would affect the quiet communities nearby. Some residents of Rogiet spoke of their fears at being "sandwiched” between the old M4 and the new motorway leading to the bridge. A councillor expressed concern over the increased level of pollution, saying the village already had a high percentage of people suffering from asthma.

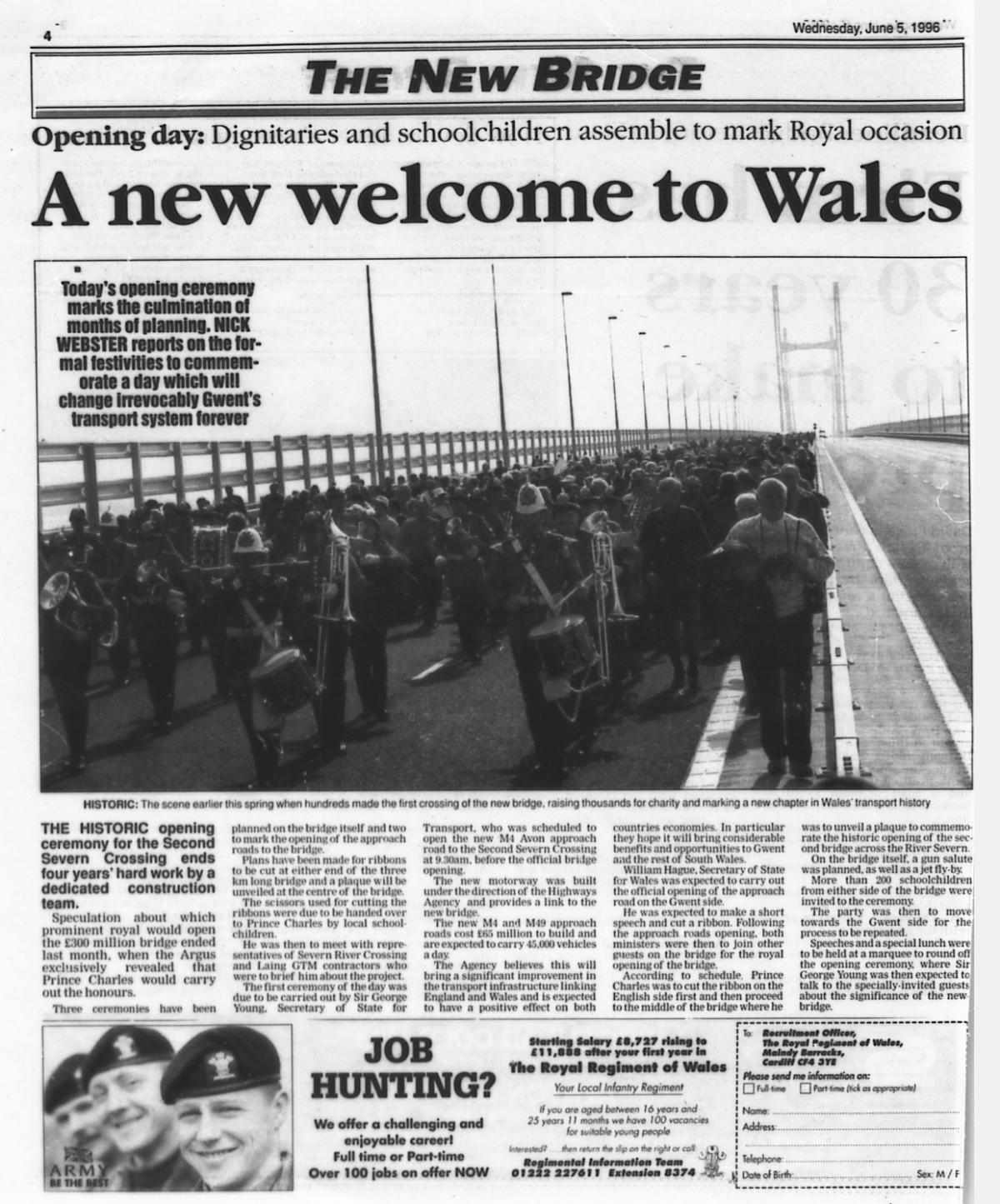

Unlike other big engineering plans for Gwent, like the Usk Barrage and the M4 Relief Road, opposition was muted and construction proceeded on schedule. A month before the bridge was opened to traffic, hundreds of people took the chance to walk across, raising thousands of pounds for charity.

While the old Severn Bridge has a pavement, this was to be the first and only time people could walk from one end of the new crossing to the other. The 5,128 metre long bridge took four years to build and was officially opened by Prince Charles on 5 June 1996. The cost of the bridge was to be recouped by charging tolls.

The deal for the Second Severn crossing was to design, build, finance and crucially, operate the bridge. Under the agreement with the government, Severn River Crossing Plc, has responsibility for managing the existing bridge and the new one. The concession will last up to thirty years.

When the company took over responsibility for the existing bridge in 1992, the toll for cars was £1 and £2 for lorries in both directions. This was changed to tolling just one way, with a charge of £2.80 for cars, £8.40 for lorries. By the time the bridge was open, the toll was £3.80 for cars, £7.70 for vans and £11.50 for lorries.

Today around 80,000 vehicles cross the bridge every day now, each paying £6.60 for cars, £13.20 for vans and £19.80.

Tolls were to rise annually by not by more than the rate of inflation, an agreement which remains in force until the concession expires.

Both the old and new Severn crossings are due to be handed over by April 2018 to public ownership after building cost debts are repaid. In his budget in March, the chancellor said tolls would be halved in 2018.

Whether this happens remains to be seen, but it is because of the tolls, rather than the astounding engineering which built the bridge that it remains a talking point to this day.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel