SHE was a cosmopolitan reporter for the Argus; drama critic and holder of a Doctorate. One of her biggest jobs for the paper was covering the Queen's state visit to Paris in 1957. Martin Wade tells the story of a most cultured Argus writer, Beatrice Worthing.

HER beginnings were ordinary enough. Born in New Tredegar in 1915, Beatrice's father was a baker. When she still a child her family moved to Newport, her mother, Edith Walters' home town.

Mr Worthing set up a bakers shop on Cardiff Road with his brother in law a Mr Williams. A family story has it that Beatrice's father had the 'secret' recipe for Clarkes' Pies.

She soon left the world of Newport and baking to study at University College in London and eventually achieving a Phd in Philosophy.

France was a place which stole her heart and was to play a big role in her life.

Her cousin Howard Hicks says she was a fluent French-speaker, adding: “She spent time with a family in France and was the nanny to their children and stayed in touch with them”.

She later wrote a book on the Belgian poet Emile Verbaeren. Her family knew of him when he was a refugee in Castleton during the First World War.

But Beatrice was no wilting academic. After leaving university, she went into teaching, including a stint at a boys’ school in England. Howard says the head was reluctant to have a female teacher in charge of a class of "unruly boys", but adds: "He gave her a trial and she passed with flying colours."

She also taught at Belle Vue School on Mendalgief Road in Newport, where she taught Howard's mother for a time.

The early fifties saw her move from university and teaching to work for the Argus.

Beatrice was commissioned by the Argus to write an article on the Queen's visit to Paris in 1957.

She was clearly overwhelmed by the spectacle of the Royal visit to that most glamorous of capitals. She wrote: “Never before or since have I seen anything as spectacular, the pageantry when the Queen and Prince Philip, escorted by the popular President Coty, sailed by night up the River Seine in a brilliantly lit bateau mouche (boat).”

When the royal couple were taken to the state banquet at the Palace of Versailles, the reporters were coralled into a holding area, unable to ask any questions or see much of what was going on.

Beatrice asked to be let out to find a phone to call her news editor. Mindful of his gruff instructions as to the type of story he was looking for, she may have been looking to break some bad news to him. But before she could make the call, Beatrice, lost in the labyrinth of corridors in the palace, she opened a door that was ajar and gazed out and as she recalled: "Inside were 500 chefs in traditional tall white hats; busily scraping the remnants of untold delicacies from priceless Limoges porcelain and swigging the remains of vintage Champagne from equally priceless Baccarat glasses."

One of them spotted her and he threatened to turn Beatrice roughly away but using her excellent French she managed to wheedle him into telling her details of the fabulous menu.

When she eventually contacted her news editor he chuckled. "OK," he said, "I'll give an extra half an inch for your exclusive new version of the ‘five loaves and fishes’ story"

In her time at the Argus, she wrote the drama diary and a weekly column in addition to court reporting and general reporting. She also wrote historical pieces on the churches of Monmouthshire, for example.

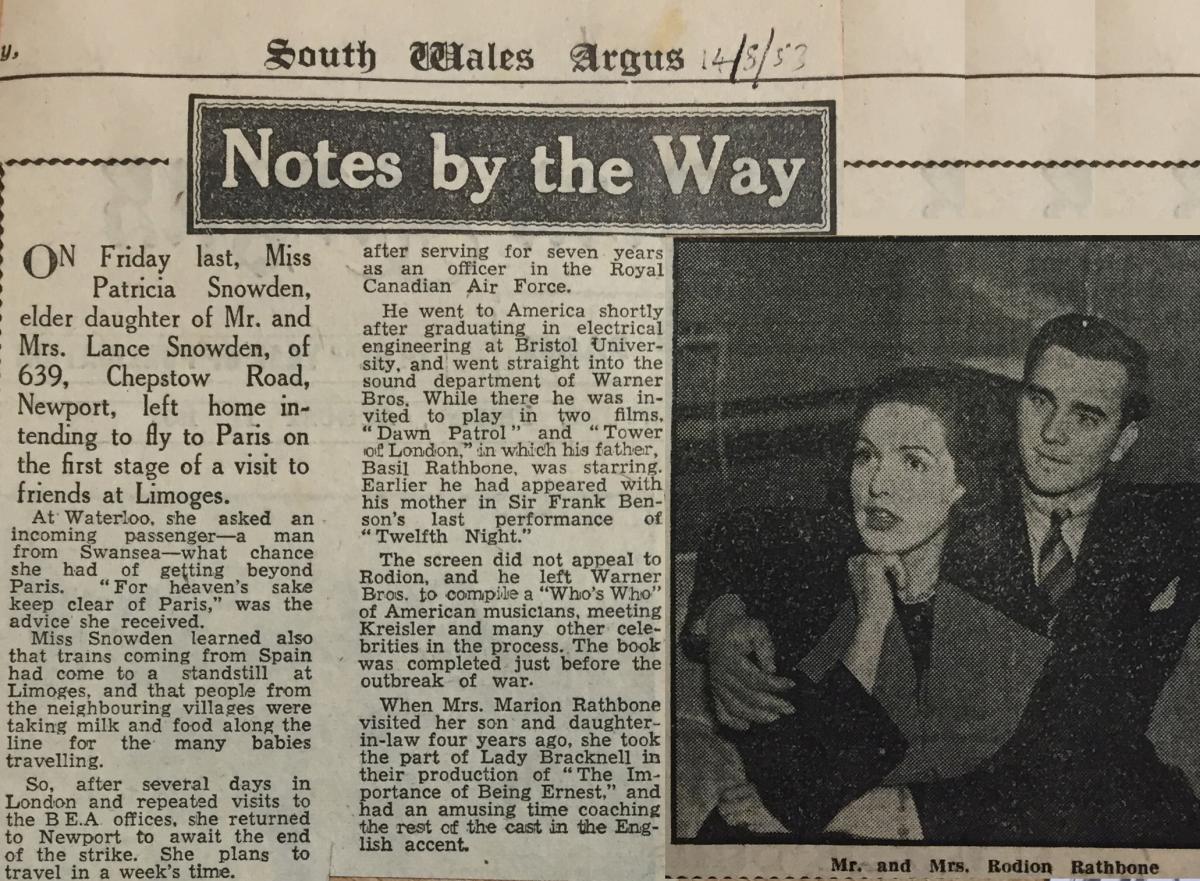

Her column 'Notes by the Way' evokes a very distant and impossibly glamorous world. It is an intriguing glimpse of the type of stories which would be covered by the Argus and other regional papers in the early 1950s.

One edition tells of a "Miss Patricia Snowden, elder daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Lance Snowden, of 639, Chepstow Road, Newport", who we are told "On Friday last...left home intending to fly to Paris on the first stage of a visit to friends at Limoges.”

Another tells of Marion Rathbone, "well-known to drama-lovers all over the county" whose son Rodion “and his beautiful American wife, Caroline have this year founded an open-air theatre on the shores of Lake Michigan”.

Rodion, we learn is not only the son of the British actor Basil Rathbone, but had starred in films with his father, acted on stage, flew with the Royal Canadian Air Force and was now a navigator with Trans World Airlines.

It is a world which newspapers like the Argus would later give over to glossy magazines, television and now the Internet. But it was not just glamour she was concerned with. Tasked with writing leader columns, she used one to plead for the building of the first Severn Bridge.

After she left the Argus, Beatrice moved to Surrey. She worked for news agencies like AFP and Reuters, but continued to write occasional pieces for the South Wales Argus.

Travel continued to feature strongly in her life and was still taking on the kind of holiday in her eighties and nineties that people half her age would baulk at.

So whether it was climbing the Great Wall of China or sharing a village hut with natives in the depths of a Malaysian jungle, she took it on. She visited Uzbekistan and even had a lift in an armoured car during one trip to Iraq.

Undaunted by turning 90, she took a flying lesson in a biplane, an experience which Howard says "she thoroughly enjoyed".

Beatrice died last year aged 100. Strength in old age must run in the family. "Her mother had survived to 105." Howard says, adding: "She was interested in everything and everyone – she was a good listener and a good talker.” Everything a good journalist should be.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel