SPORT is a passion prized by the military. What drives someone to succeed on the pitch will do so on the battle field. Rugby players from Monmouthshire served with distinction in the First World War and two Newport players did so in the Battle of the Somme.

They died in battle and played no more. Martin Wade recalls the Newport players who fell during the Somme offensive.

Gwent writer Mike Rees uncovered many stories of the exploits of Welsh sportsmen at war when researching his book: ‘Men Who Played the Game: Sportsmen who gave their life in the Great War’. The two Newport players who died at the Somme were exemplary in their own way.

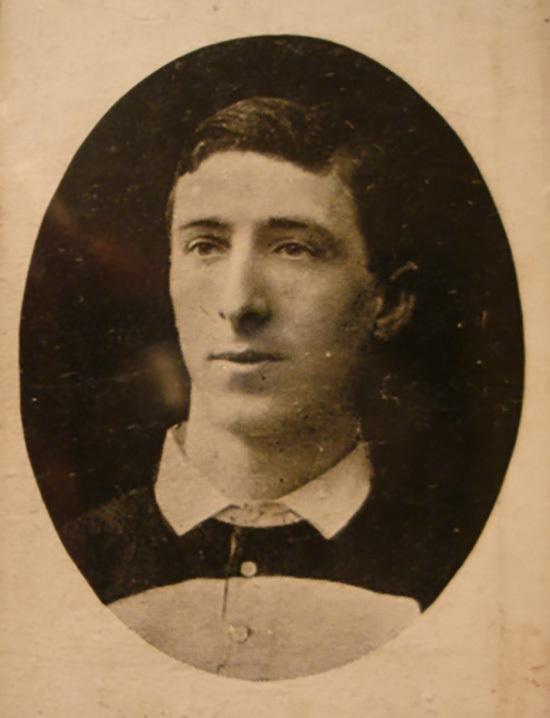

One, Mike says, is “a true man of Newport”, Charles Meyrick Pritchard. Charlie was the son of John Pritchard, a founder member of the Newport Rugby Club and part of a family that ran a wine and spirit business. Following an education at Newport Intermediate School and Long Ashton, Bristol, Charlie joined Newport RFC and by 1904 the 22-year-old, thirteen stone, six feet tall version of the modern back-row forward was in the Welsh team.

By 1905, he was part of the Black and Ambers team which narrowly lost 3-6 to the touring All Blacks.

Later that year he lined up with Wales to face the mighty New Zealanders. Mike explains how big the game was: “They arrived in Cardiff unbeaten to be challenged by a strong Welsh team and Charlie was to play a huge part in what many regard as the most important match in rugby history.” Wales deservedly won a thrilling, controversial match 3-0 but, although it was Teddy Morgan who scored the try, Charlie was the inspiration.

This, one of the 14 caps he’d win for Wales, was surely the most important, in a match that is still recalled today. His aggression had, according to George Travers, a fellow hero and club colleague, "knocked 'em down like nine pins."

Others talked of his willingness to be in the thick of the fight, disrupting the hitherto invincible All Blacks with his devastating tackling. Following this victory Charlie’s fame was assured but his career didn’t end there. In 1906 he was made captain of Newport, a position that he held for three years.

Charlie would have won more had it not been for injury. He played in the championship winning Wales team of 1906 and in the first Grand Slam success in 1908. After missing out on a second Grand Slam in 1909, Charlie played his last game for Wales in 1910.

With the outbreak of war, Mike tells how Charlie was quickly promoted. “He joined the South Wales Borderers as a temporary Second Lieutenant in May 1915, then became a lieutenant at the end of July and was made a captain in the 12th Battalion the following October.”

Following a period of training, he arrived on the Western Front in June 1916 in time for the Somme offensive and was quickly pressed into action. Mike tells how Charlie was tasked with leading his men on night-time raiding parties at Choeques, to capture German soldiers who could be interrogated. “This was difficult work”, Mike says. “They often were forced to take cover in the long grass from their own bombs and struggled to avoid the German searchlights.”

A raid in August was to be fateful. On the night of August 12-13, Charlie was instructed to lead a raiding party on the German trenches with a view to taking as many prisoners as possible. The aggression and willingness to be in the thick of the fight showed that night as Mike explains: “He led his men into the trenches showing incredible bravery and even though he was wounded in the wrist, he continued to encourage and lead his men in taking an enemy prisoner.”

But Charlie was wounded once again, taken back to the British front line and then to a casualty clearing station shortly before dawn on the wet morning of August 13th. “His concern was not for his own comfort but for the success of the mission” says Mike. “Have they got the Hun?” Charlie asked as he lay injured. “Yes” he was told, “Well I have done my bit,” Charlie replied, the last words that he was known to speak. He died, without ever leaving the clearing station, on August 14th 1916. He was 32-year-old.

Mike explains the devastating effect Charlies’ death had on his unit. “His commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander wrote to the family telling how his death had ‘cast a gloom’ over the whole battalion and describing Charlie as being ‘as brave as a lion’.”

Others spoke of the deep affection in which he was held, the fine example that he set as to what a sportsman should be and his “private tenderness” who was “loved by all who came into contact with him”.

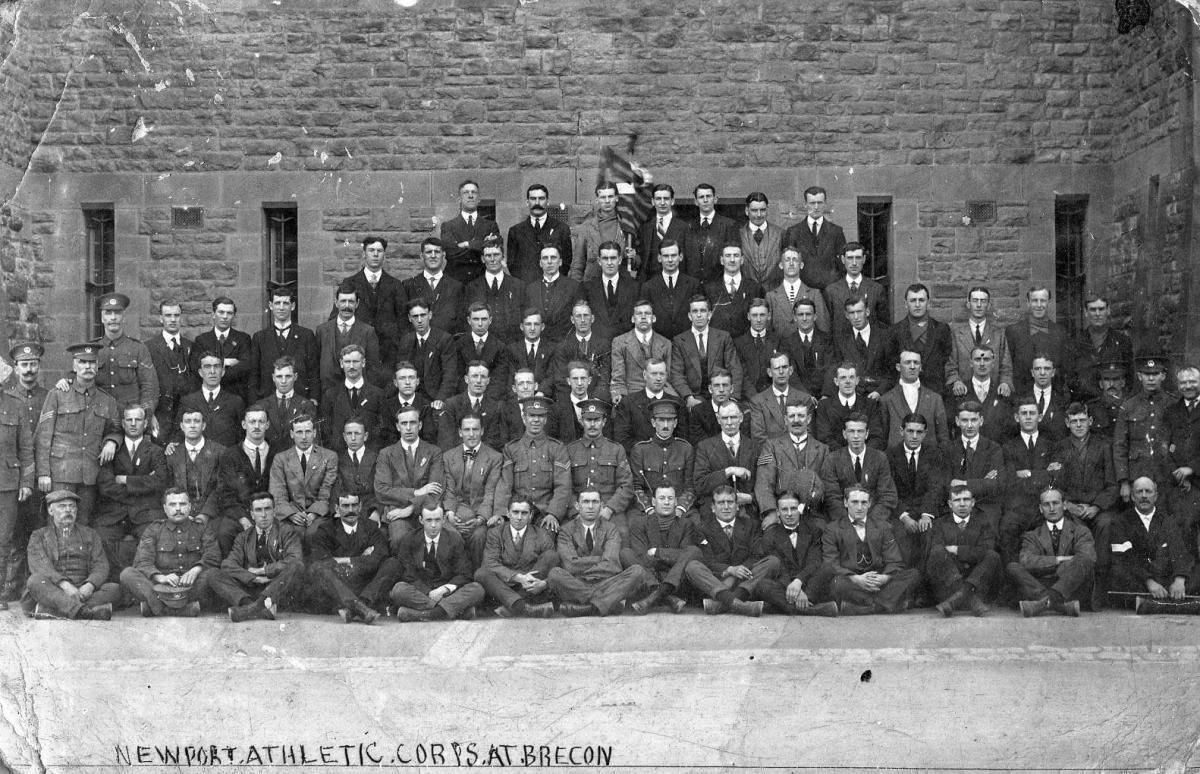

Charlie was buried in Choeques Military Cemetery and for his bravery was Mention in Dispatches. He is one of 86 members of Newport Athletic Club who lost their lives in the First World War and is remembered on the Memorial Gates at Rodney Parade. Mike is sure of his place in history: “He left not only a grieving widow with two young children at their home on Llwynderi Road in Newport but the legacy of a true Welsh rugby hero.”

For Mike, there is another Welsh rugby player whose career started in Newport who should be remembered.

“John Lewis Williams was the most capped Welsh international to die in the whole conflict” he says. The prolific wing had begun his career at Newport in 1899 and won his first Welsh cap against the Springboks in 1906 going on to.

Noted for his swerve and sidestep, Mike sees him as one of the greats: “He scored a record seventeen tries in seventeen internationals, he was an integral part of three Wales Grand Slam winning teams in 1908, 1909 and 1911,” adding “there are only a handful of Welsh players to achieve anything like that.”

In 1908 he played his seventeenth and final match for Wales in the victory over Ireland.

When war broke out Johnnie joined the 16th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Regiment. July 1916, in saw him at Mametz Wood, a place where thousands of Welshmen were to die.

The action, intended to take the forest in just a few hours, took six days, such was the ferocity of the German defence.

Mike tells how Johnnie met with the murderous German fire. “He went over the top at the start of the battle on July 7 but heavy machine gun fire cut him and many of his comrades down. Johnnie was severely wounded and his left leg was amputated.”

Infection set in and, although he was able to write to his wife Mabel that he was in good spirits, Johnnie died of his wounds on 12th July. He was one of 190 officers and 3,803 other ranks who were casualties at Mametz.

His wife of just eighteen months was left a widow but his reputation as one of the great Welsh wings, however, remains firmly intact.

‘Men Who Played the Game: Sportsmen who gave their life in the Great War’ by Mike Rees is published by Seren Books and is available in all good bookshops across Wales and the UK.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel