A NEWPORT man who became a soldier in a cavalry regiment fought at time when horses gave way to tanks for the first time. Martin Wade tells the story of Percy Lacey who also left his family dramatic pictures of the devastation wrought by the battles on the Somme.

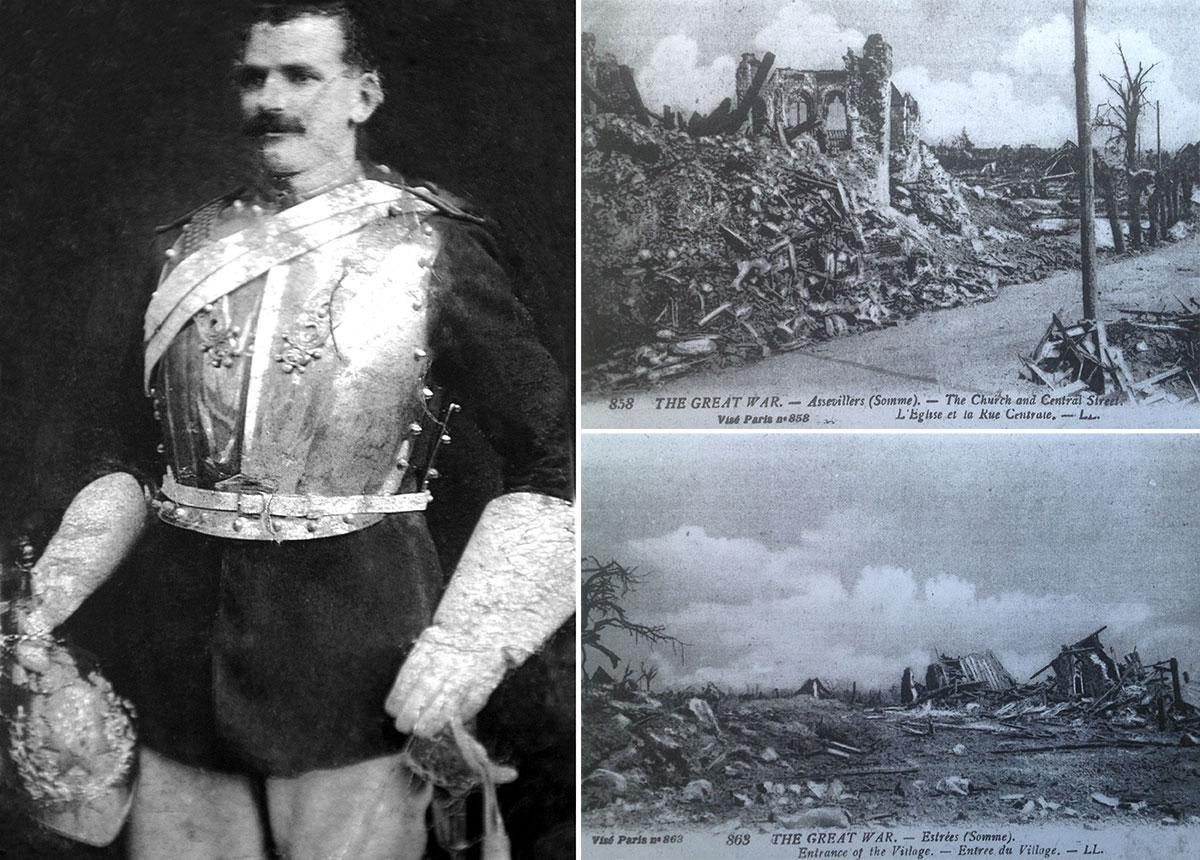

ROGERSTONE man Les Lacey is quietly proud of his grandfather. Looking every inch the cavalryman in his gleaming breastplate and plumed helmet it would be hard not to be. But Percy Lacey didn't come from the usual background for a mounted regiment.

A cavalry unit may have been an unusual home for a Pontypool steelworker, but Percy had seen a different life before he came to work in industrial Gwent.

As a farm labourer in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, he learned to shoe horses, Les says. “He came looking for industrial work before the war, but his skill with horses meant the cavalry was the right place for him to be.”

When the war was over, Les tells how he was still was a horseman: "He kept a horse and cart off Glebe Street in Maindee and sold eggs from the cart. I know people who still remember him doing this."

He first joined the 2nd Dragoon Guards, then the 6th Dragoon Guards before joining the Household Cavalry. During his service with these famous cavalry regiments he worked mainly as a shoeing smith, and was entrusted with caring for the hooves of the horses, what in civilian life would be called a farrier.

Although millions of horses were used by both sides during the First World War, the conflict would see the tank replace the horse as the way to get across a battlefield safely and swiftly.

Cavalry was found to be too vulnerable to the effects of shrapnel and of machine gun fire, but before the tank was proven, both British and French commanders continued to put faith in the power of mounted soldiers.

An action during the wider Battle of the Somme involving Percy's unit, the 2nd Dragoon Guards, was to show these two ways of war-fighting in sharp relief.

The Battle of Flers-Courcelette fought between 15-22 September 1916 saw tanks used for the first time. The monstrous iron machines trundled across the mud, immune from German rifle and machine gun fire. Although in places they spread panic among the Germans, more succumbed to engine failure than to enemy fire. But the small numbers used had shown their promise.

Mounted cavalry were only used once in the Battle of the Somme, when a charge was made by an Indian cavalry regiment. At Flers-Courcelette it was planned that cavalry units would charge and exploit successes made by foot-soldiers. However, although the battle saw many objectives reached, cavalry could not be deployed. The 2nd Dragoon Guards, like other horse units served dismounted or on foot. The dismounted men mainly carried out reconnaissance patrols.

The scene of hundreds of horses waiting to go into battle is one that is hard to conjure now.

A contemporary of Percy’s in his unit, the 2nd Dragoon Guards, wrote on the eve of an earlier battle: “All that could be heard was the clip-clop of horses' feet, creaking of saddlery and champing of bits.

"Now and again the sound of a muffled cough. I had never seen so many horses and men together at one parade. It was an awe-inspiring sight. Dragoons, Lancers, Hussars - they were all there, as well as Indian mounted troops.”

It was a sight that would become rarer and rarer, before disappearing altogether.

Soon tanks would replace the horse entirely. And for all the spectacle of the massed ranks of cavalry, the horse’s war was almost always a tragic one, with only a few thousand returning from the First World War.

Amid many grim scenes of battle, a particularly sad sight Percy must have seen many times was the grisly proof required that a horse was dead.

So valuable were the animals that if a soldier's horse was killed or died he was required to cut off a hoof and bring it back to his commanding officer to prove that the two had not become separated.

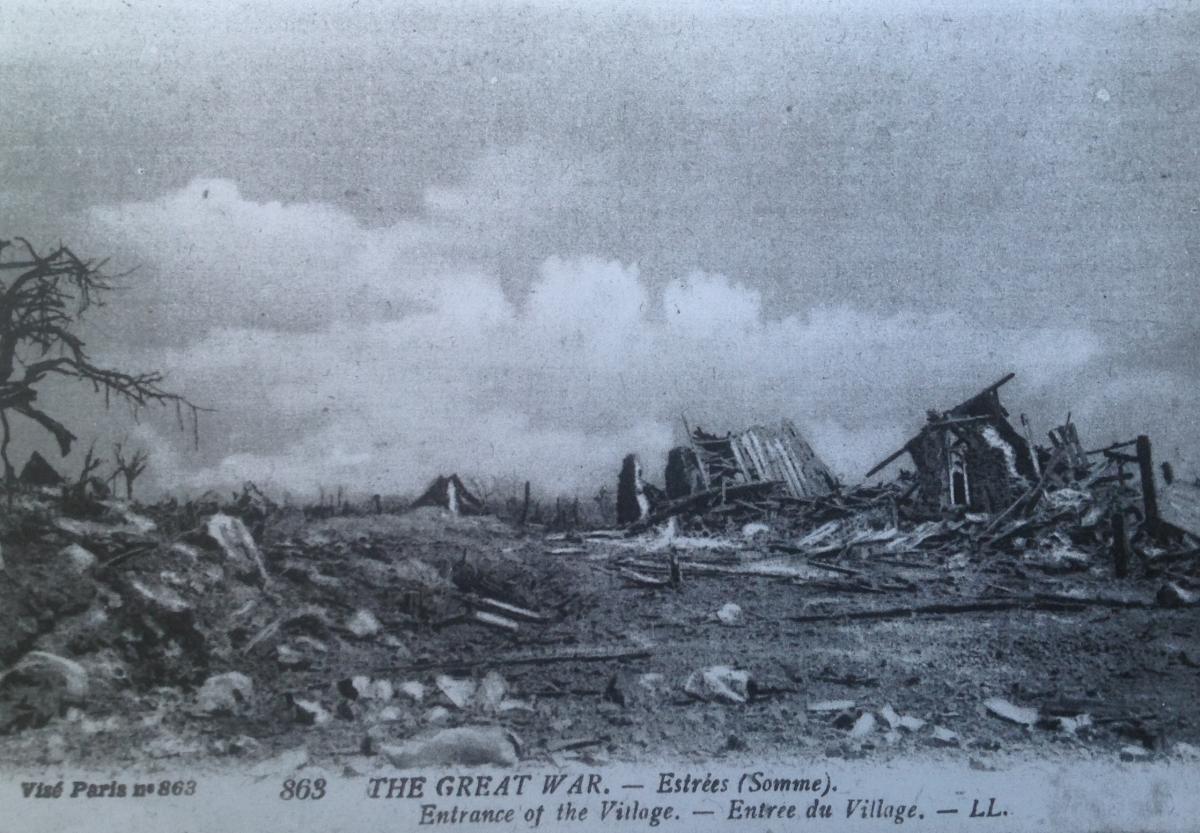

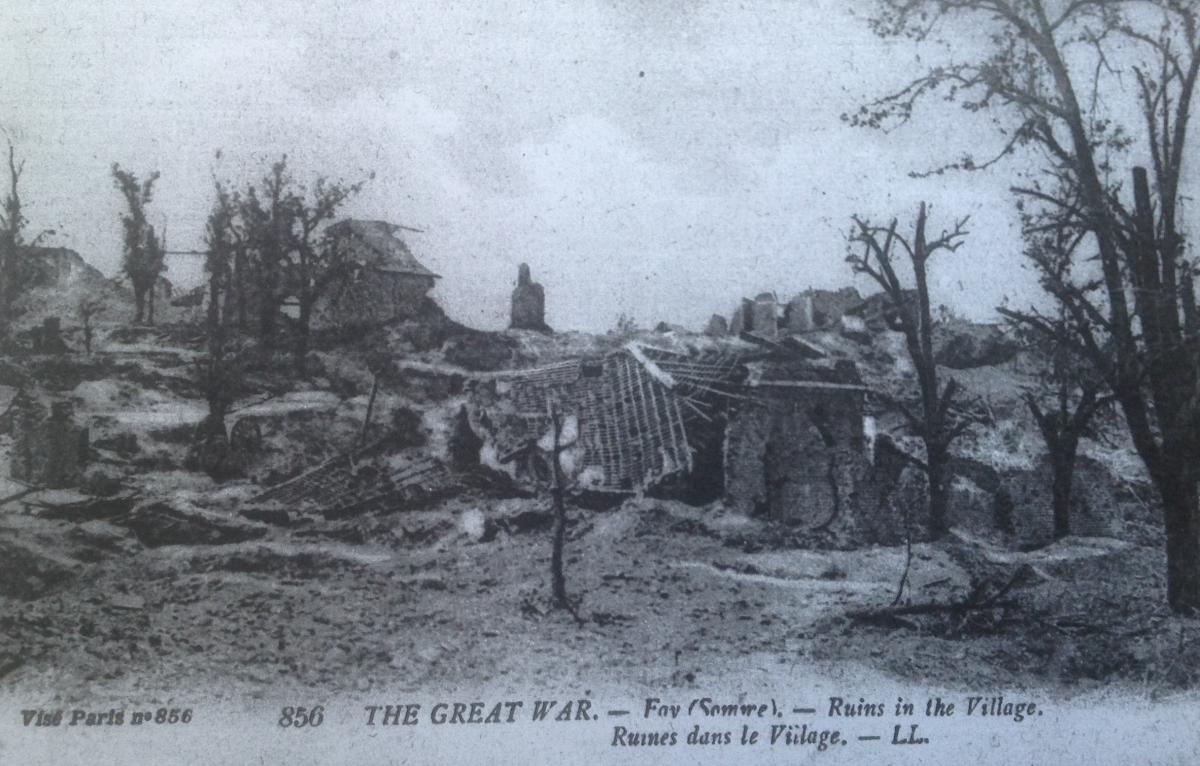

One of the links Les has with his grandfather is a series of postcards left to his family depicting the scenes of destruction left after the fighting on the Somme.

The cards, which are written in French as well as English, show a village called Foy devastated by bombardment. Another depicts the ruined town of Biaches with a forlorn street sign and the shell of a sugar refinery. Another shows the village of Assevillers, its ruined church the only recognisable feature, while others show villages utterly flattened by shellfire.

They are a sobering reminder of the havoc wreaked, not just on the bodies and minds of the soldiery, but also the heavy price paid by those unfortunate enough to live close to the battlefield in the valley of the Somme.

"They're still in perfect condition after all these years. He must have had a job keeping them like after they were issued out there." He adds: "The edges are perforated, so they must have been given out as a sheet of cards, like stamps."

The purpose of the postcards seems to be one of propaganda. Similar cards produced by the Daily Mail during the war veered from uplifting scenes of British fighting men to views of devastation brought by German fire.

While many soldiers sent their crads home, Percy instead chose to keep them pristine and later hand them down. Those pictures, although perhaps intended for propaganda still have value in showing graphically the devastation brought to the towns and villages of the Somme valley. The picture of Percy, handsomely moustached in his breastplate tells of another era too, of cavalry charges and of war horses, which died with that terrible war.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here