A HUNDRED years ago, thousands of Welshmen were thrown into the hellish Battle of Mametz Wood. Among those fighting was a battalion recruited from the coalfields and ironworks of Western Monmouthshire. Martin Wade recalls the 10th Battalion South Wales Borderers or the 'Gwent pals'.

A week after the bloody start of the Battle of the Somme, The 38th Welsh Division was tasked with seizing Mametz Wood and its capture was seen as the key to a successful attack on the German second line in the area.

Facing them in the forest was the elite Lehr regiment of Prussian Guards. These were well-trained professional soldiers, who defended the forest with mortars and machine guns in their dugouts.

It was thought the wood could be taken in a matter of hours, but 400 were killed as they came up against heavy German fortifications and machine-guns.

The 38th was raised in 1914, originally intended to be a 50,000-strong Welsh Army Corps, it was championed by David Lloyd George. Among the great and good of Monmouthshire life who sat on the Corps' committee was Frederick Mills, the Director of the Ebbw Vale Iron and Steel Company. His enthusiasm was to be vital in recruiting hundreds of Gwent miners and steelworkers together in one fighting unit.

Pontypool man Gavin Rees was inspired to research the battalion's story when he discovered his grandfather’s great-uncle had served with them. "I was interested in the localness of the battalion. It was based so much on where people lived and worked."

Gavin says: "Among the ten South Wales Borderers battalions that served during the First World War, the 10th were unique in that they were the only one formed on the lines of a 'pals' battalion, comprising of colliers and iron workers from the towns of Western Monmouthshire."

“Sir Frederick Mills was keen to raise a local battalion in the Welsh Army Corps and he was sure he could raise the men from among his workers in Ebbw Vale and Cwm and recruitment opened in November 1914. “

More than 100 men enlisted on the first day; from Ebbw Vale came colliers, company officials who would be commissioned as officers in the battalion.

Mills imagined he could muster an entire battalion primarily from his businesses in Ebbw Vale, but the numbers fell short. Many men who worked at local collieries and steelworks had already been recruited, so the net was spread wider to neighbouring towns of Abertillery, Abercarn, Blackwood, Cwmcarn and Tredegar.

The attack on Mametz Wood began at 8.30am on July 7 and quickly descended into chaos. The Welshmen were cut down 300 yards short of the wood. Another attack two and a half hours later met with the same fate. By the end of the day, the 38th had made no progress but 177 men and three officers had lost their lives.

Siegfried Sassoon, known now as a war poet, was an officer in the 2nd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers and fought at Mametz Wood. He told of: “The doomed condition of these half-trained civilians who had been sent out to attack the Wood,” and how they met with “massacre and confusion”.

Still the Welsh were thrown into the forest that was alive with machine gun fire and shrapnel. The Germans, secure in their dugouts, hidden among the trees, poured fire on the Welsh and held their ground.

Field Marshal Douglas Haig blamed the Welsh Division for not advancing “with determination to the attack”. Commanding Officer of the Welsh Division, Maj-Gen Philipps, was held responsible for the lack of progress and was removed.

His replacement, Major-Gen Watts was ordered to attack early on July 10. The attack was on a much larger scale than the previous efforts. Heavy casualties were taken but progress was made. As the edge of the wood was reached bayonets were fixed and brutal hand-to-hand fighting silenced a number of German machine guns.

The 10th were in the teeth of this fighting. A miners’ agent called Edward Gill had been given the task of raising a company from Abertillery. Well-liked by the miners, over 200 men enlisted in the battalion and Gill himself was commissioned as a Captain and became machine gun officer of the battalion. He had earlier won the Military Cross in March 1916.

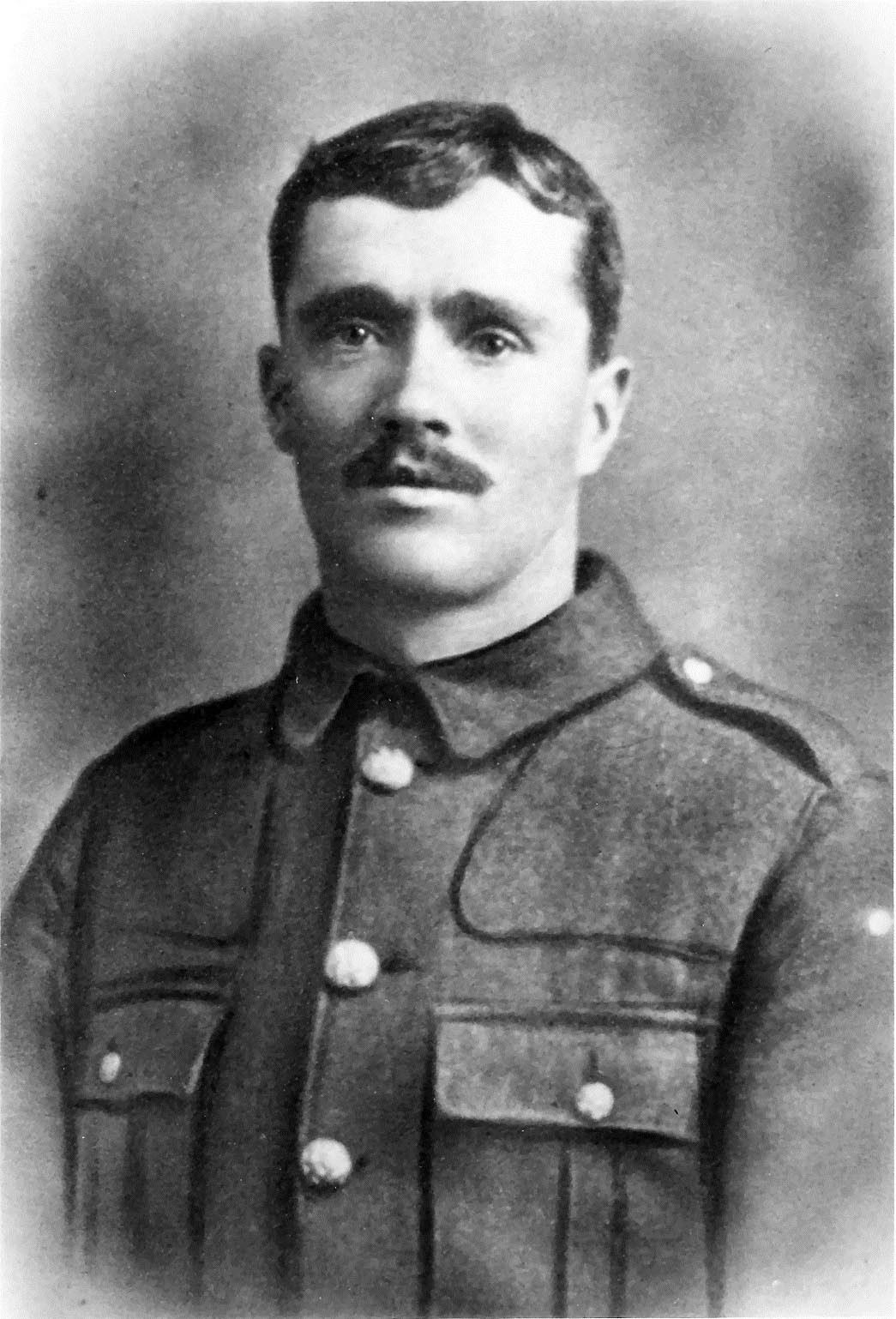

Gill was badly wounded in the attack on Mametz Wood and left in no-man’s land. Gavin tells how the relative he discovered launched a daring rescue. “He was a collier from Beaufort called Lawrence Bull and he went out under enemy fire with stretcher bearers to rescue him.

RESCUER: Sgt Lawrence Bull

“The rescue party came under shell fire and Gill was wounded twice more before they were able to dig in and wait for night to come.” Darkness was no guarantee of safety and the Germans would continue to fire blindly through the night. The stretcher party made to the dressing station and he was saved. Speaking while in hospital, Capt Gill tells how Sgt Bull "would not leave him for hours, and stayed with him among the fast-falling shells."

Perhaps the most famous of the 10th Battalion was a soldier from Cwm who would become Wales’ most decorated soldier of the war. John Henry 'Jack' Williams VC was a blacksmith at Marine Colliery and he, like hundreds of his workmates, was one of these 'Gwent pals' of the 10th.

He went on to be awarded the Victoria Cross, Military Medal and the Croix de Guerre, but his first award, the Distinguished Conduct Medal, was earned during the Battle of Mametz Wood.

HELLISH: The painting 'Mametz Wood' by Christopher Williams

Of those thousands killed at Mametz Wood, 33 were of the 10th. Most of those died on July 10, when the offensive was stepped up. One of them was Cwm man Fred Ludlow. He was 31-years-old. His grandson Dustin Pitman has travelled to Mametz Wood many times, an experience he finds profoundly moving. “To look at it now, it’s so peaceful, like Somerset where he came from. There are fields of barley and wheat.” But he adds, “You can go into the woods and pick up bits of ammunition, things like that. You’re sometimes afraid to look too far for fear of what you might find.”

Dustin isn’t sure about how his grandfather died, but knows that some were cut down by their own artillery. “It is a haunting place - It never quite leaves you.” He adds: “The voices haven’t gone. You can stand there in the wood and feel their presence.” A hundred years on we too should remember those voices of the Gwent workers who joined up with their pals to fight and never came home.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel