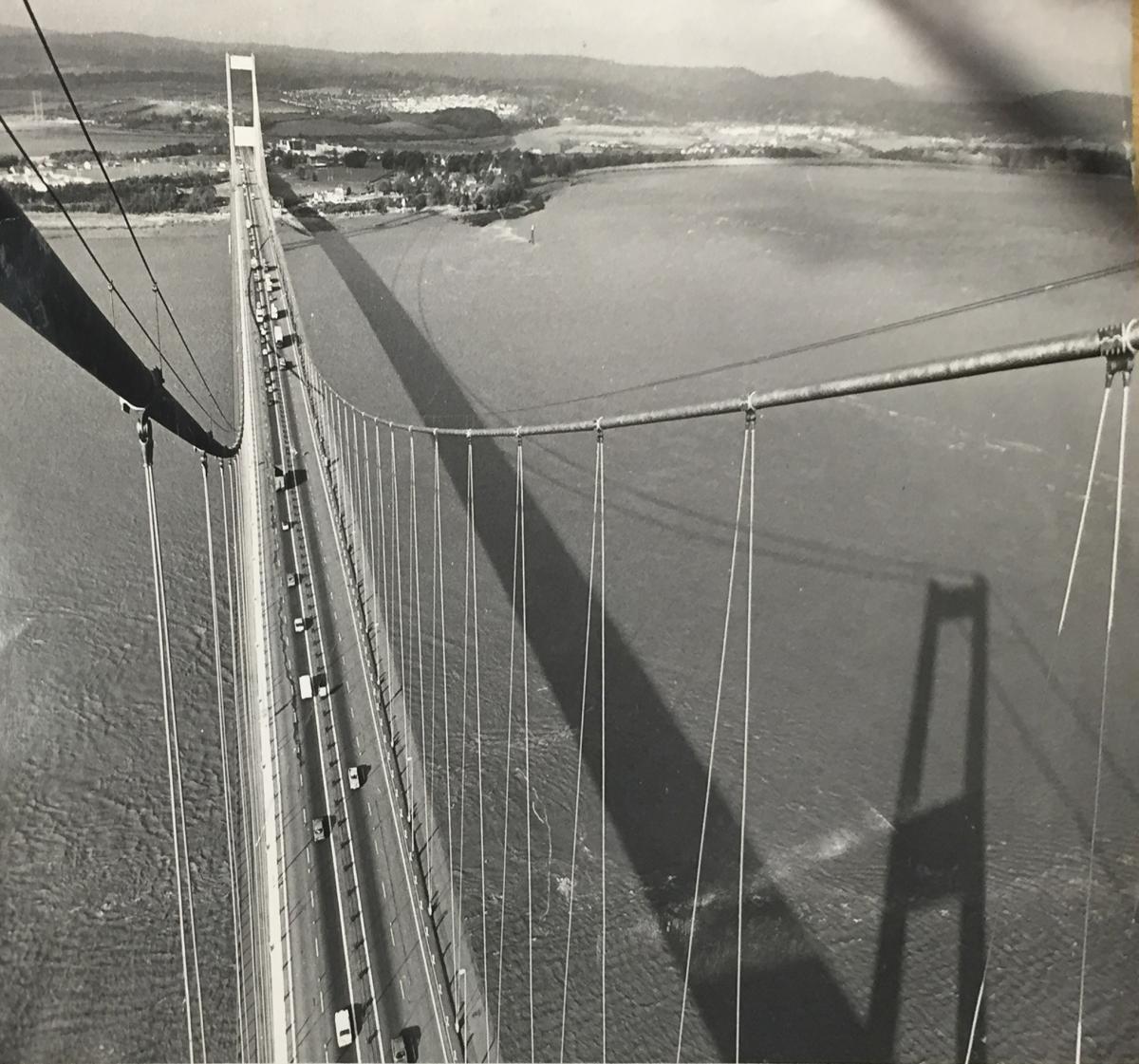

In the last of his features marking 50 years since the opening of the Severn Bridge MARTIN WADE looks at the building of the bridge and how pioneering work helped it overcome this dangerous river.

It was a project of mind-boggling numbers. Cables made up of 8,000 wires, concrete anchors weighing 90,000 tons, a span of nearly 10,000 feet and it cost a mere £8 million. There is much about the building of the Severn Bridge which was awe-inspiring but also new.

Construction work began in 1962, but before then, much work was done to make sure the design would work in this unforgiving place.

Designs were tested at the National Physics Laboratory in Teddington where models were placed in wind tunnels. After one model was destroyed by simulated high winds, the designers changed tack. Making the cross-section of the bridge shaped like that of an aeroplane's wing meant wind resistance was reduced by almost a third. The new shape also cut the amount of metal needed to build the bridge deck.

Although suspension bridges were commonplace by the time the Severn Bridge was designed, they had not been without their problems. A similar bridge in America over the Tacoma Narrows literally shook itself to pieces after winds set the bridge swinging. The risk from high winds forced the designers to incorporate a pioneering feature into the bridge. The lines hanging from the main cables which supported the roadway were key to stopping this problem. In America, high winds had caused theses cables and the deck to swing back and forth. Previously these would have been hung vertically, so that once they started swinging they would be difficult to stop. The new technique had the cables hung diagonally to form the triangular pattern we see today. This meant that any movement would be 'dampened' by this new design.

The site gave engineers a series of challenges. Where it was decided the river would be crossed, between Aust and Beachley, the river is a mile wide at its narrowest point. The bridge had to cross, not just the River Severn, but also the Beachley peninsula and the River Wye before it could land safe on the Welsh side. Lastly, perhaps the biggest challenge was the wildness of the river. Its tidal range was huge, with the water rising or falling by 13 metres four times a day and the waters would rush in and out as the tides changed.

The bridge is actually made up of four separate bridges. The first is a suspension bridge across the River Wye, next is the Beachley viaduct which crosses the small peninsula, actually in England. Then comes the largest section, the suspension bridge which crosses the Severn itself. Then the Aust viaduct carries the roadway from the suspension bridge to the top of Aust cliff on the English side.

The difficult work began by building the Aust Viaduct on the Ulverstone Rock, some 1,500 feet from the Aust Cliff. This rock was beneath the water for most of the day, but work could be done for a couple of hours if the tide was right. Hollow blocks, made of reinforced concrete, were bolted onto the rock in the brief window the river allowed. They were ten feet high and weighed 2.5 tons each and slowly they were set into the rock and then filled with concrete. This was carried on until they reached a height of 63 feet.

The vast towers stand 400 feet high and support the weight of the road and the cables. Each tower is designed to carry a weight of 8,000 tons. They stand sentinel-like and are instantly recognisable.

The huge cables, slung over the towers reach without a break from one shore to another. Each of the cables contains 8,322 strands of wire, each a mile long and these are squeezed together to form a cable about 20 inches across. These vast metal ropes are held in place by concrete anchorages 160 feet long and 132 feet high. They weigh 90,000 tons each as anything less would mean the cables would drag the structure away.

The cables hang between the towers with the roadway suspended beneath in a way which suggests clothes hanging from a line. Only of course what hangs off them is a little more weighty.

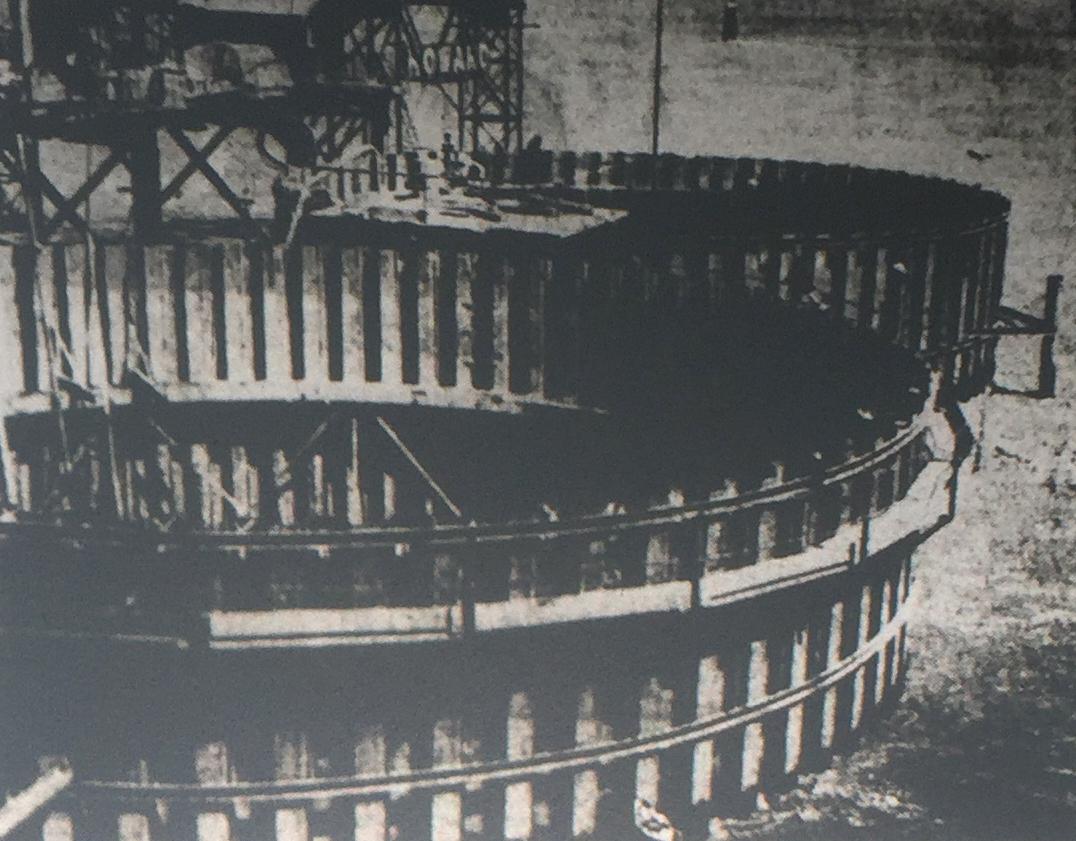

The operation to build the roadway resembled the building of the floating 'Mulberry' harbour used on D-Day. The road was made up of 88 plates which were hollow pontoons. Each of these 130 ton sections were made from prefabricated parts in England and assembled at Fairfield Mabey in Chepstow. From there they were launched from the slipway where ships were once made and floated off down the Wye into the Severn where they were steered beneath the bridge and hoisted into place.

Engineer John Evans thinks he's probably the only one left who worked on the building of the Severn Bridge and is still involved with it.

He worked on the Welsh-side building the piers supporting the bridge and anchorages Beachley. His work showed the battle with the Severn in sharp relief. "We built the piers on a piece of land exposed at the lowest tide and we laid a temporary staging to reach it."

From there they sank great metal piles to form two vast coffer dams. The piles eventually formed a water-tight enclosure from where they excavated to bare rock. "From there we filled the coffer dams with reinforced concrete to about 40 feet above the rock."

Reminders that they were taking on the natural forces of the river were ever-present. "The Severn ferries would sail past us as we worked at the bottom of the pit 70 feet below."

It wasn't just the tides, currents and strong winds on the river they had to overcome. "The winter of of 1962-3 was extremely cold." John recalls. "There was very heavy snow and even ice floes on the river. Quarrying for stone stopped until the March."

Meanwhile, the work continued. "At the time we were building the Beachley anchorage" (where the vast cables would be secured). "There we had to dig 70 feet down until we hit rock - then we would build up from there with reinforced concrete to 70 feet above ground level." The vast size of the anchorage was needed to secure the weight of the cables.

Next John worked on the bridge over the River Wye and the Beachley viaducts. Here, he recalls, the same team would go on to work on the George Street Bridge in Newport.

Unlike many of the engineers working on the bridge, John lived locally then and has stayed there ever since. "We bought our house in Redwick in 1964 as I was working on the Severn Bridge. I've worked in Hong Kong, Australia and elsewhere in the UK, but never long enough to move away permanently."

He works today as a consultant engineer near Chipping Sodbury and so often has to cross over to England. Which bridge does he use? "For convenience and for old time's sake I mostly use the old bridge", he says. "One of the joys of the old bridge" he adds, "is that you can see the estuary - it gives such a wonderful view."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel