On this day 75 years ago a Newport street was destroyed and eleven people killed in a night of carnage when German planes brought death to Rogerstone. MARTIN WADE recalls the attack on Park Avenue.

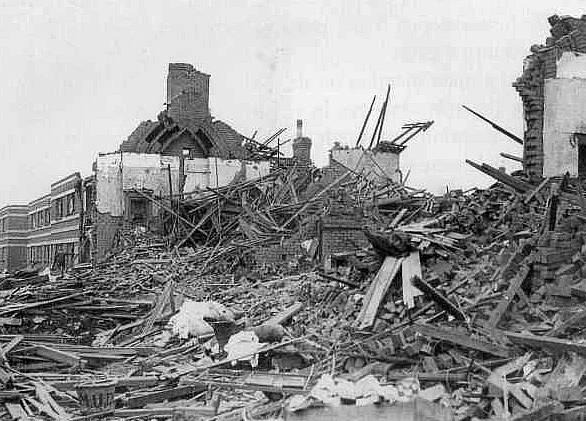

IT was bright, moonlit night when the quiet of a Rogerstone street was utterly shattered. Terraced houses were blown to pieces, their bricks, carved lintels and glass, all were smashed and hurled out in a wave of deadly shrapnel.

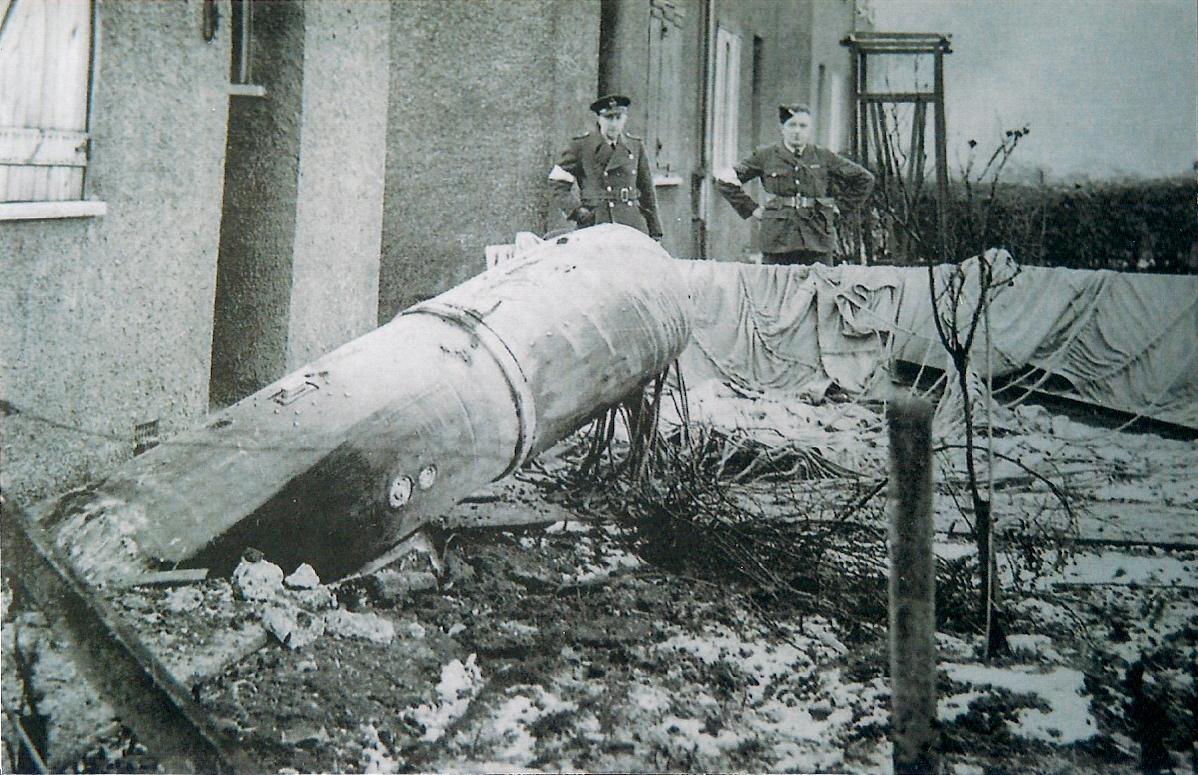

The weapon which brought death to Park Avenue that night was not a bomb which whistled as it fell. Rather it was known as a 'parachute mine'. Derek Picken of Rogerstone Local History Society says that although the name 'parachute mine' sounds innocuous it was far from it. "Some imagine them to be like a small land mine, but they were great tubular things, six to eight feet long and 18 inches in diameter".

These weapons were originally developed for sea warfare and the Germans first dropped them over land in September 1940. Weighing up to 2,000lb, a parachute would open as they fell from the bomber, letting its deadly cargo drift silently towards the ground.

On the night of October 7 the air raid siren was sounded at 8.20pm. Then all that was heard was distant gunfire until around nine o'clock, and then an aircraft was heard travelling very fast down the valley towards the coast. As it reached Rogerstone, a searchlight scanned the skies to illuminate the bomber. Instantly the plane dived and was seen by many, including air raid wardens and firewatchers. Two large bombs were released trailing parachutes and they could be seen drifting down.

The parachute mine was designed to maximise the effect of blast and to detonate at roof level rather than on hitting the ground. This way none of the impact of the blast would be absorbed by the earth.

The shock waves from the explosion could then reach a wider area, potentially destroying a whole street of houses in a 100m radius and blowing out windows up to a mile away.

Joan Picken lived in Risca at the time and heard the blast. “The following morning I passed through the village on my way to Cardiff where I was going to college.”

“It was shocking to see it. So many houses were just destroyed.” Her future husband Dennis Picken was in the Home Guard and he helped clean up after the bombing.

One of the mines had fallen in a field making a large crater. The other had utterly destroyed a number of homes with others having to be demolished. Almost 130 houses were made uninhabitable.

Bound by wartime censorship, the Argus could only allude to the "South Wales coastal town" which was hit by "bombs dropped by moon raiders in a nearby village".

It noted that it was the first time “for some weeks” that heavy anti-aircraft fire was heard in this unnamed town.

It told there were "some casualties, including a few dead, and a large number of houses damaged."

The raid was over quickly and rescue parties and first-aiders were on the spot within a few minutes, and worked throughout the night.

Edward Satherley was invalided out of the Army after serving in France during the German invasion. He recalled hearing gunfire and "seeing something falling from the sky". The next thing he remembered was being blown "about 40 yards" by the blast of the bomb. He ran to a house opposite and helped rescue Edward Gibbons whose hands he could see showing above the debris. His own house was damaged. "I have lost practically everything" he added.

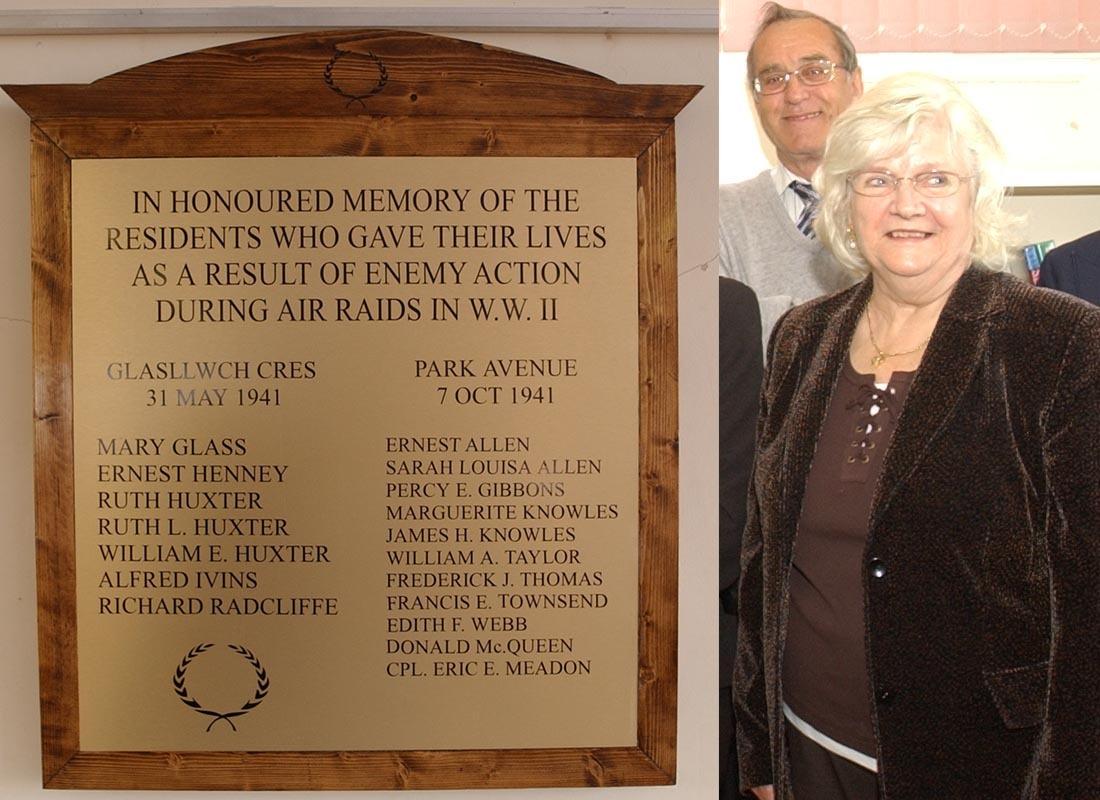

Eleven people died that night when death rained down on Rogerstone. Three of those killed were fire guards. James Henry Knowles, William Alfred Taylor and Edith Flora Webb died trying to protect their village. Also killed were Earnest Allen, Sarah Louise Allen, Marguerite Knowles, Frederick John Thomas, Frances Ellen Townsend, Corporal Eric Edwin Meadon and most poignantly Donald McQueen. The 13-year-old had been evacuated from London with his brother to avoid the heavy bombing of London. The quiet Monmouthshire village near Newport must have seemed perfectly safe compared to the bomb-scarred streets of the capital.

The devastation that night had an impact not just on those who died and their families, but for those who saw the carnage which visited Park Avenue. That sight of devastation stayed with Joan Picken and it was something she thought later generations should be told about.

“It always astonished me that there was nothing to tell people what had happened here” she says, “nothing to commemorate that awful night. So many years after it happened, I began campaigning for a plaque to be put up”.

It was a campaign that eventually bore fruit and her questions to councillors and letters to the press paid off when a memorial was put up in memory of those who died. “It was very satisfying when we the plaque went up in Rogerstone Library” Joan admits, “finally there was some way people could know that those eleven died that night.”

The memorial also remembers victims of an attack on Glasllwch Crescent in which seven people died.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel