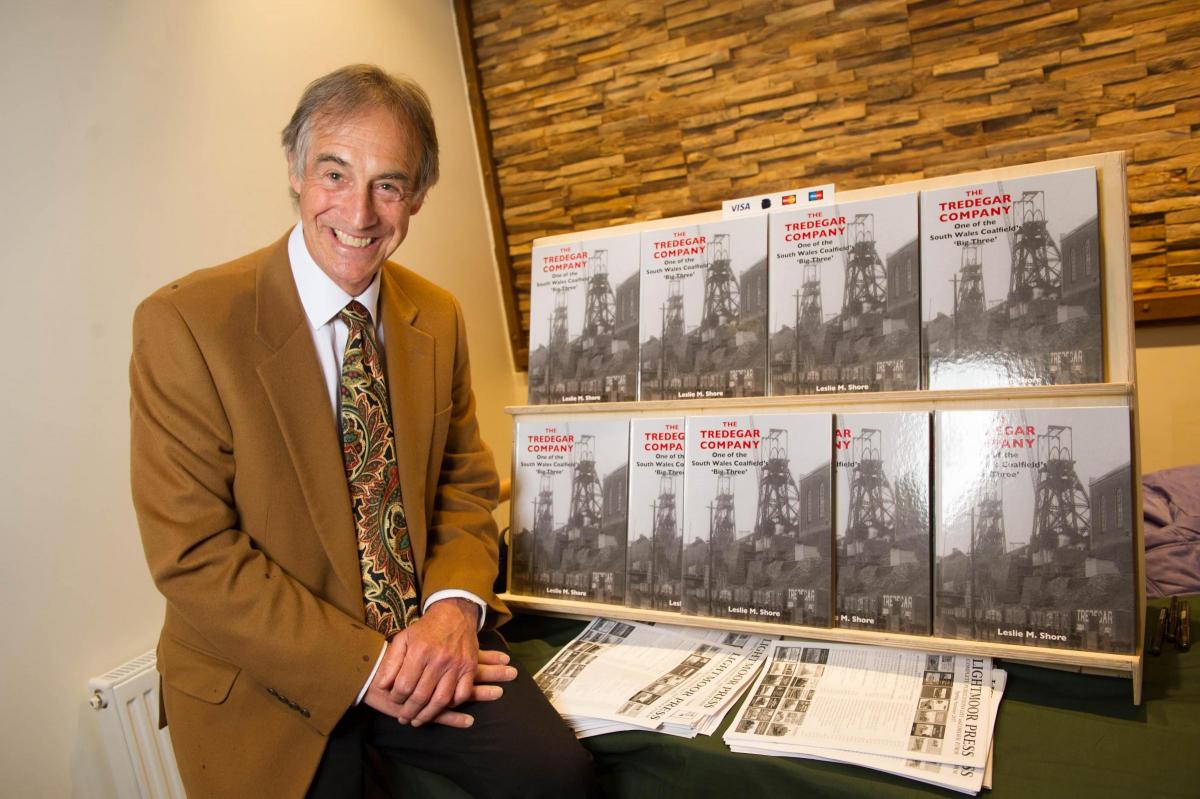

A new book about a famous Gwent company shines a light on the rise and fall of two great industries of Wales, iron and coal. MARTIN WADE talks to Leslie Shore, the author of The Tredegar Company.

COAL could be said to be in Leslie Shore’s blood.

Aged 67, he was born and raised in New Tredegar in the Rhymney valley.

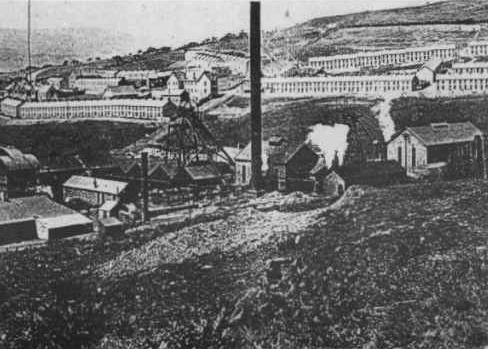

During the first two decades of his life, the town had as its centre a busy Elliot Colliery.

His grandfather, and great-grandfather all worked at the colliery and his father worked as a colliery engineer.

But it never gave him a living as it did his forebears.

His story reflects that of many in South Wales who, as the industry declined, chose not to work for ‘king coal’.

Although he himself became an engineer, he found work in the industry that took its place – oil. Working around the UK, he settled in Cumbria, where he still lives.

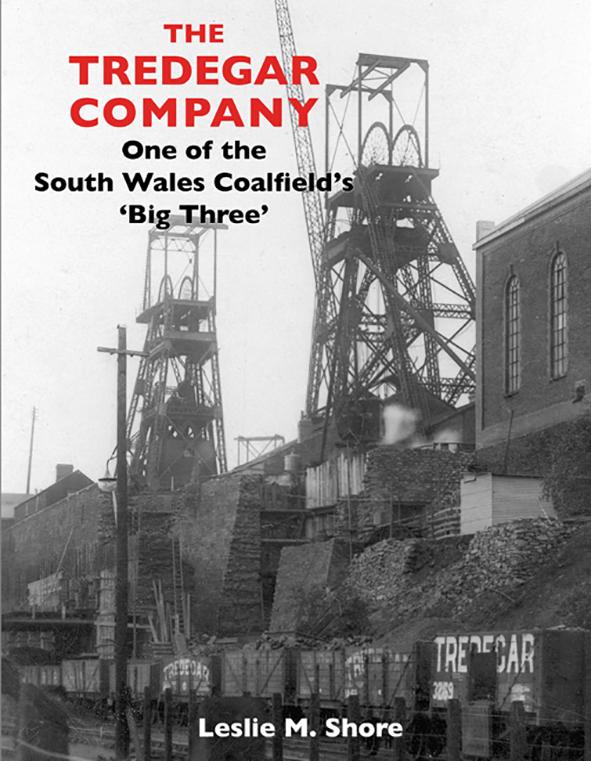

Mr Shore had written other books on mining in South Wales, but buoyed by the “unbelievable” response to his last one ‘Peerless Powell Duffryn’ on one of the other great mining companies, he started work on another.

He admits too that “so much information came to light, he wanted to compile it and make sense of it”.

A family connection also played a role.

His wife’s father AJ (Jack) Edwards was a mechanical engineer who began his working life as an apprentice with the Tredegar Company at Oakdale Colliery.

He also served as chief draughtsman for the National Coal Board in west Monmouthshire. A collection of his documents relating to the company and the coal industry now sit in the Gwent Archives in Ebbw Vale and they have provided Leslie with a horde of information.

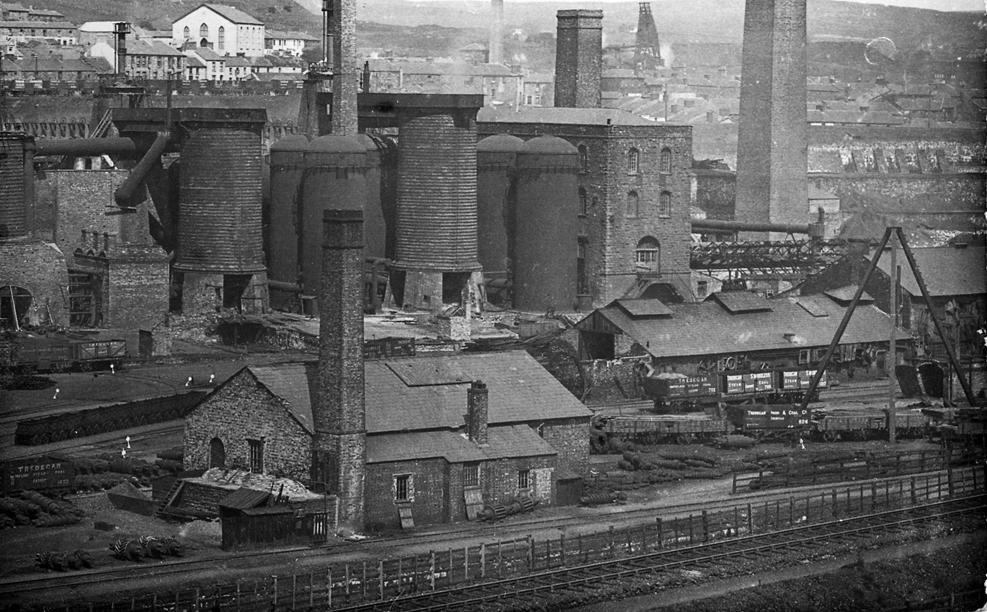

The story of the Tredegar Company is in many ways, Mr Shore says, is the story of much of Gwent for almost two centuries.

“That story charts the rise and fall of two great industries of Wales, iron and coal” he added.

The Sirhowy Valley with its outcrops of coal, clay ironstone, and limestone took on great value once knowledge of a metal-working spread.

Mr Shore explained: “By the mid-1770s the Darby family, who were ironmakers in Shropshire, were firing coal as a bi-product called coke, mixed with an iron ore and limestone, to smelt iron in a blast furnace.

“In 1778, men drawn from beyond South Wales formed a partnership to open a coke using blast furnace, called the Sirhowy Furnace, at the head of the Sirhowy Valley.”

“The Sirhowy furnace came before others here such as Blaenavon, Beaufort, and Ebbw Vale,” he says, and with the building of the Monmouthshire canal the ambitions of ironmakers in the county were boosted. Two Sirhowy Furnace partners in particular, Thomas Atkinson and William Barrow, wanted to build a much bigger operation.

“They 1800 joined up with Samuel Homfray, the Merthyr Tydfil ironmaster, to found the Tredegar Ironworks,” added Mr Shore.

Homfray, through marriage, had strong ties with Sir Charles Gould Morgan, who ran the Tredegar Estate from Tredegar House.

Demand for iron to make weapons during the Napoleonic Wars increased and helped make the ironworks a viable business.

Later, the Tredegar Ironworks rode the wave of demand as the railways exploded in Britain and around the world. But alongside iron production, coal was becoming more and more important.

By around 1840, the Tredegar Iron Company, as it was then usually called, was branching out and was supplying the coal market beyond the Sirhowy Valley.

Some went to meet the demand from the railways, but more still was needed to power ocean-going ships.

“This would prove a lucrative business for around three-quarters of a century,” said Mr Shore.

Bedwellty Pits, opened in 1853 to the south of the town of Tredegar, was the first key investment made in the valley to raise coal to supply this steam coal market.

The last quarter of the 19th Century and later saw the company open more and more collieries across Gwent, shaping the landscape, forging names – Markham, Oakdale, Wyllie, we still know today.

This work carried on apace through the early years of the 20th century. These years between the turn of the century and the outbreak of war in 1914 would see coal exports from Cardiff peak in 1913 and the first million pound deal struck at the city’s coal exchange.

Mr Shore calls this was a crucial time for the company.

“The opening of the Rhymney Valley colliery can be said to mark when the company took a crucial step towards becoming centred as a coal business.

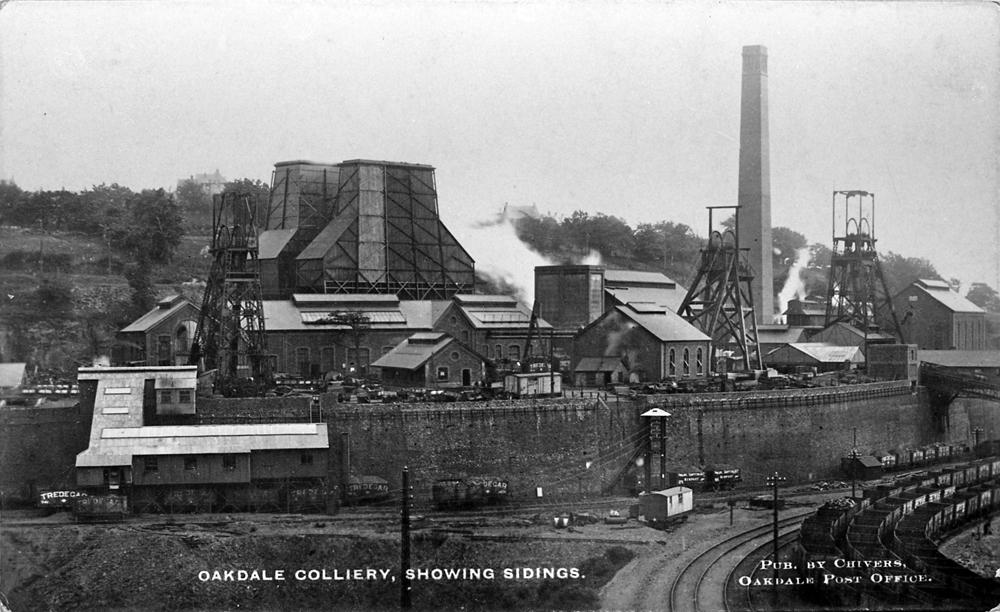

“The founding of Oakdale Navigation Collieries between 1907 and 1911 was a major investment, showed the ambition of the firm.”

By 1913, the company added Markham Colliery to the north of Oakdale.

The company sank its last colliery, Wyllie, in the 1920s, south of Blackwood. The inventive Tredegar Company introduced electricity into the South Wales coalfield to power colliery plant and equipment. Over in Torfaen, it was the pioneer in the British coalfield of steel arch roof supports for underground use.

By the early 1920s the Tredegar Iron & Coal Company was one of the ‘Big Three’ companies of the South Wales coalfield, which was then Britain’s most important coalfield.

Alongside the growth of the company in commercial terms, they showed concern for their workers.

Mr Shore added: “The company supported the idea, in 1873, of its workers setting up of the Tredegar Workmen’s Medical Aid Scheme.”

The outlook of two company directors, Sir Charles McLaren and Sir Arthur Markham, was influential in shaping the business.

Mr Shore said: “Both men were radical Liberals, and they encouraged policies within the company such as the building of planned villages featuring well-designed housing for colliery officials and workers.”

Just as the company left its mark on the Sirhowy Valley with the mines it sunk, so it did with the communities it built.

“One general manager of the company, AS Tallis, had a profound effect,” Mr Shore states. “He opened three collieries, and oversaw the building of at least two villages, Abertysswg, and Oakdale. Later other communities like Markham and Wyllie were built.

After the First World War the demand for steam coal began a steady decline. Agitation grew for better pay and conditions for miners.

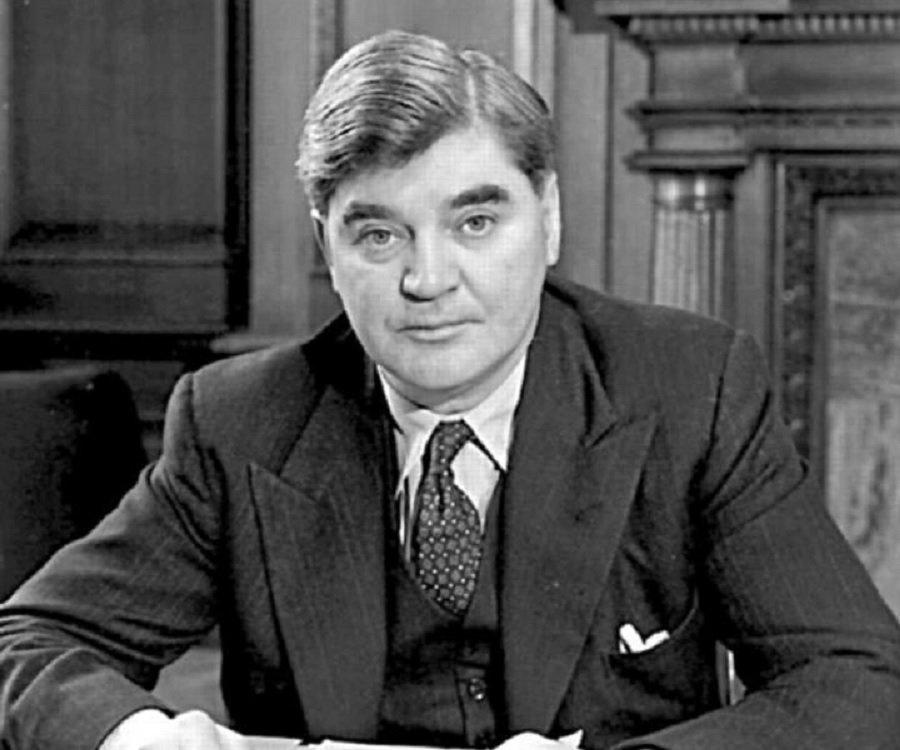

Among their leaders were company workers Harold Finch, who would later become MP for Bedwellty and one Aneurin Bevan. Both men served as miners’ leaders during the long 1926 strike. Bevan, as health minister, famously used the Tredegar Workmen’s Medical Aid scheme as a model for the foundation of the National Health Service.

But with the nationalisation of the British coal industry in 1946, the Tredegar Iron & Coal Company ceased to exist and its collieries became assets of the National Coal Board (NCB). The late 1950s saw former Tredegar Company collieries begin to close as coal reserves became exhausted.

One which survived was Oakdale Navigation Colliery. Reflecting the firm’s earlier role, it supplied coal to make coke for metal production at the Spencer Steelworks in Llanwern.

But pit closures continued and the miners’ strike of 1984-85 failed to stop the shut down of mining in Gwent and across the UK.

Oakdale was to be the last pit in Gwent to close. The survival of the last Tredegar Company colliery was “remarkable” Mr Shore says, but despite the costly investment by the NCB and the considerable efforts of its workforce, the colliery closed in August 1989.

Read how Tredegar gave Confederates the weapons to fight the civil war

The results of those changes are all around us, from the towns that sprang up and live on, to the abandoned pit workings, gone and grassed over.

Books like Mr Shore’s are invaluable in helping us understand such great change to this part of the world and this company which made it happen.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel