THOUSANDS cross it every day and pause to think only of the tolls they have to pay. But one man has been inspired to write of the Severn and the stories behind its crossings. MARTIN WADE talks to Chris Witts.

The Severn has loomed large for much of his life.

When Chris left school at 16, he already had a fascination for the river that saw him join the crew of a tanker barge which traded in the Bristol Channel. He worked as a deckhand with John Harker Ltd loading petrol at Swansea and taking it as far up the river to Worcester.

His passion for the River Severn had been kindled when as a 14-year-old when his mum gave him a book about the river.

Chris is 73 and lives in Gloucester.

Now, the 73-year-old Gloucester man has committed that passion for the river to paper with the publication of a history book The Severn estuary crossings.

Although he has worked the Severn since he was a boy, Chris admits he never began studying the river in earnest until about 25 years ago.

The river is a famously dangerous and difficult body of water to cross. Chris says: “It was once the barrier between two countries, but now with the choice between two bridges and a railway tunnel, crossing the estuary is taken for granted.”

It was not always so. For thousands of years travellers wanting to cross the Severn had to risk a ferry crossing over dangerous, wild tidal waters or take the 60-mile detour via Gloucester.

The Romans worked a ferry between Aust and Beachley linking Bath and Caerleon, calling the route the Via Julia Maritima.

The crossing was a treacherous one. The tidal range of the Severn is the second-highest in the world, with 13 metres of difference between low and high tide. The funnel shape of the estuary means as these tides change vast quantities of water rush up and down between England and Wales, creating vicious and dangerous currents. A steam ferry began to ply the crossing in 1827 making the crossing somewhat safer, but still the traveller was at the mercy of the tides and the weather.

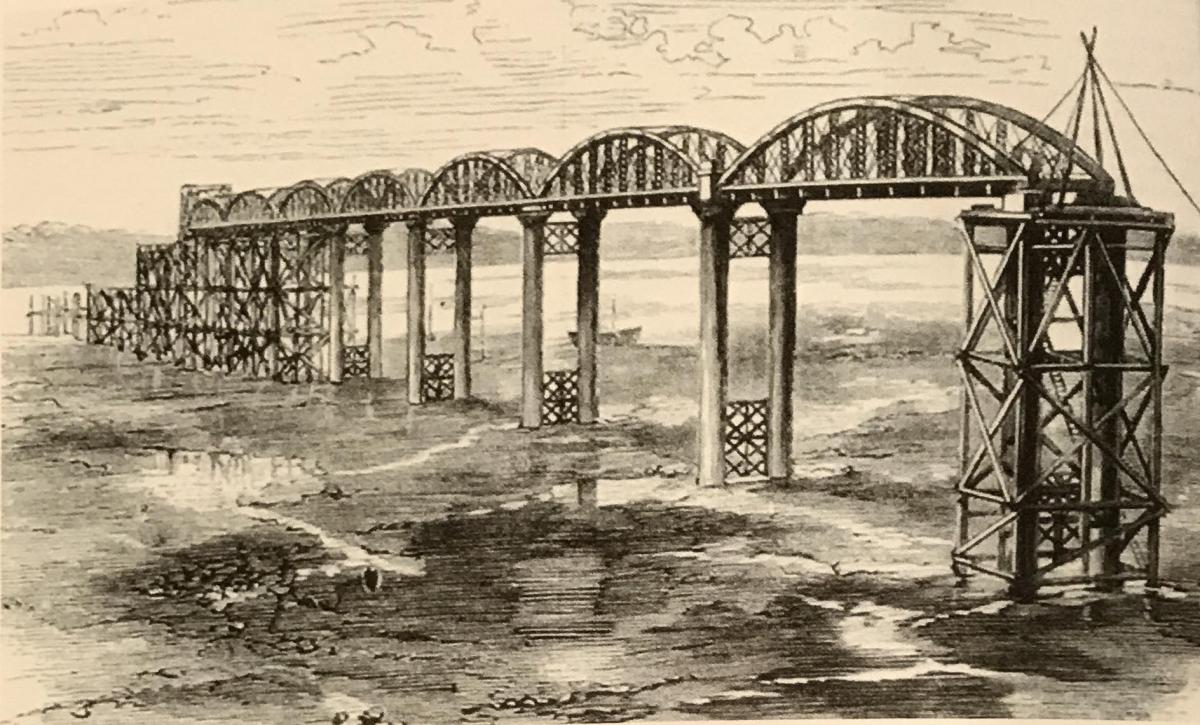

Although not linking Wales with England, the Severn Railway Bridge at Sharpness opened in 1879 and crossed to Lydney on the opposite side of the river. The single-track bridge was preceded by the four-mile Severn tunnel which was completed in 1866.

The railway bridge is gone now, but its end came relatively recently and it is one of Chris’ early memories of the river.

Not long before the Severn Bridge was built, the railway crossing still stood. But on October 25 1960, Chris recalls how he was on a barge called the Wyesdale H, in the Severn off Sharpness.

“A thick fog descended onto the river and our sister vessel, the Wastdale H and another tanker barge, the Arkendale H hit the bridge and brought down two spans.” As they fell, parts of the bridge hit the barges causing the fuel they were carrying to catch fire, causing a massive explosion.

Five men were killed, including Malcolm Hart, a fellow deckhand on the Wastdale H who, Chris said: “I had spoken to only minutes before”.

The spans of the bridge left standing were eventually pulled down, but the wreckage of the Arkendale H and the Wastdale H can still be seen when the tide is right on the river.

But before the Severn Bridge was opened in 1966, if you were driving, the quickest way to cross the river from England to Wales was by ferry.

Although there had been a ferry across the Severn at roughly the point where the bridge would be built since at least Roman times, a steam ferry service closed with the opening of the Severn Tunnel in 1866.

The ferry service gained a new lease of life, however, with the growth of motor traffic, and a service was re-opened in 1926. Between 1931 and 1966, a ferry service was operated by Enoch Williams of the Old Passage Severn Ferry Company Ltd.

The railway still eyed what traffic the ferry services ran and in 1924, the Great Western Railway started to take cars on railway wagons through the tunnel between Pilning and Severn Tunnel Junction as an alternative to the Aust ferry. With its erratic timetable determined by the tides, or the long road journey via Gloucester, this was seen as a more reliable service.

Taking the ferry was not without its hazards. As car ownership grew, so did queues at Aust and Beachley for the ferry.

It was a short but difficult route to sail across the ever-changing tides. Because the ferries had to cope with tidal ranges of up to 13 metres, they had no keel, which made it easier to cope with the lowest of tides. This also made them more difficult to steer.

The ferry held no romantic allure for Chris.

“I never crossed the river on the ferry” he admits and adds: “Not many really liked doing it”.

He says it sounds romantic today, but that allure can only be conjured with a hefty dose of hindsight and rose tinted glasses he says.

“Cars used to queue for hours waiting to board, then there were mishaps with the odd vehicle ending up in the Severn.

“My dad in his old Austin 7 flatly refused to use the ferry when we lived in Bristol when I was a young boy. It was always the long detour up to Gloucester and back down the other side of the river.”

The service continued until the opening of the Severn Bridge in 1966.

Many of the crew members found jobs on the bridge and on the day it opened, the three ferries took their bow and gathered by the crossing. As the Queen drove across the bridge to open it they sounded their hooters signalling the end of the ferry ride across those difficult waters.

The bridge, when it was opened just over 51 years ago was seen as a marvel of design.

Making the cross-section of the bridge shaped like that of an aeroplane’s wing meant wind resistance was reduced by almost a third. The new shape also cut the amount of metal needed to build the bridge deck.

By 1984 traffic across the first Severn Bridge had tripled and it was projected that by the mid-1990s the old bridge would be running at capacity. It was decided a new bridge was needed.

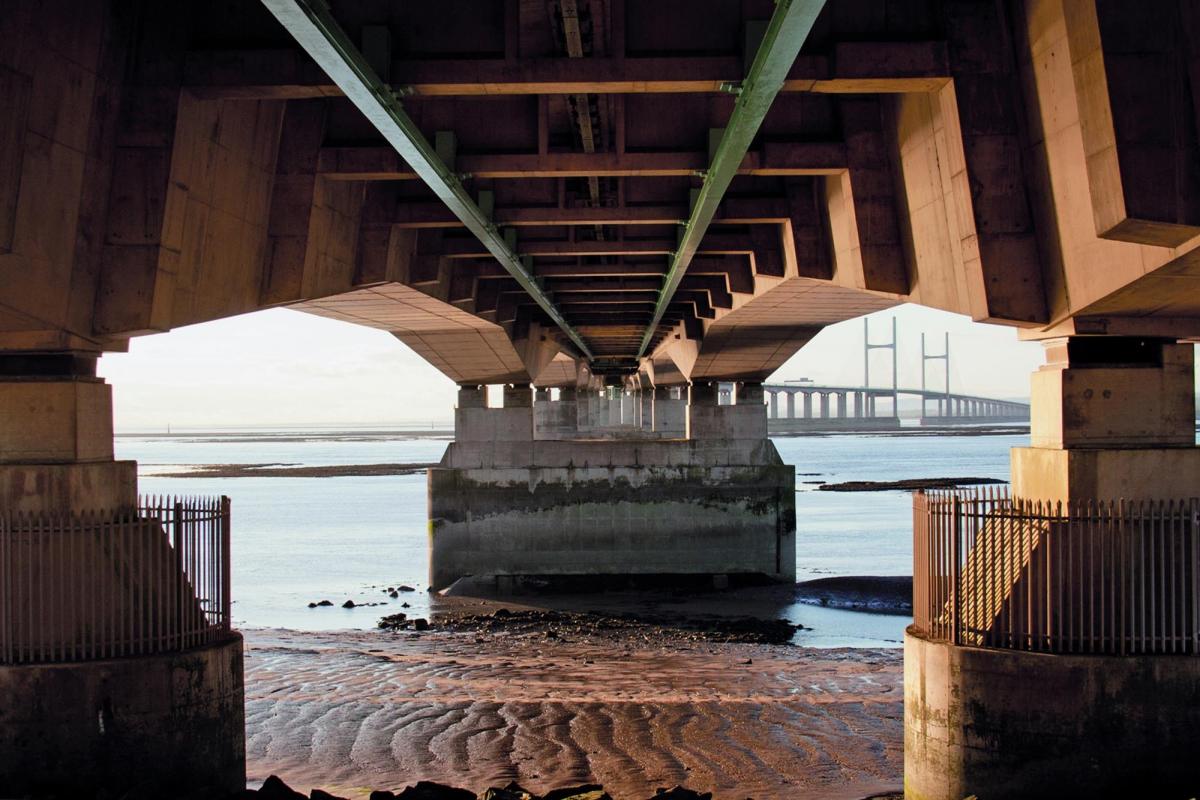

Opened in 1996, the Second Severn Crossing was built with space-age technology.

Its 37 enormous concrete piers which carry the bridge were built near the site of the bridge. They were taken by powerful tracked vehicles similar to those which transported the Space Shuttle to its launching pad.

The 2,000 tonne monoliths would slowly be carried to the water’s edge to be loaded onto a barge, which would take them to be positioned by laser-beam over its precise location on the estuary bed.

Despite this cutting-edge science, of the two bridges, Chris is clear which of the two is his favourite is. “It is without doubt the [old] Severn Bridge, is in fact my favourite of all the bridges [across the Severn] from source to sea. The story of how the bridge was built is remarkable for its time and the end result looks so magnificent as it spans the estuary.”

But the building of this crossing had a price and Chris remembers all too clearly a day when this was paid.

Again Chris was working on one of the Severn barges carrying cargo up and down the estuary.

He recalls one autumn day in November 1961.

“We were bound for Swansea on the evening tide out of Sharpness and whilst tied alongside the Wharfedale H, we hit a rescue launch close to the Severn Bridge, which was then under construction. A man on the launch died – he was the first person to be killed during the building of the Severn Bridge.”

Six men were to lose their lives in the building of the bridge.

Both the danger and the wonder of this special river are told in The Severn Estuary Crossings by Chris Witts, produced by Amberley Publishing and is priced at £14.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here