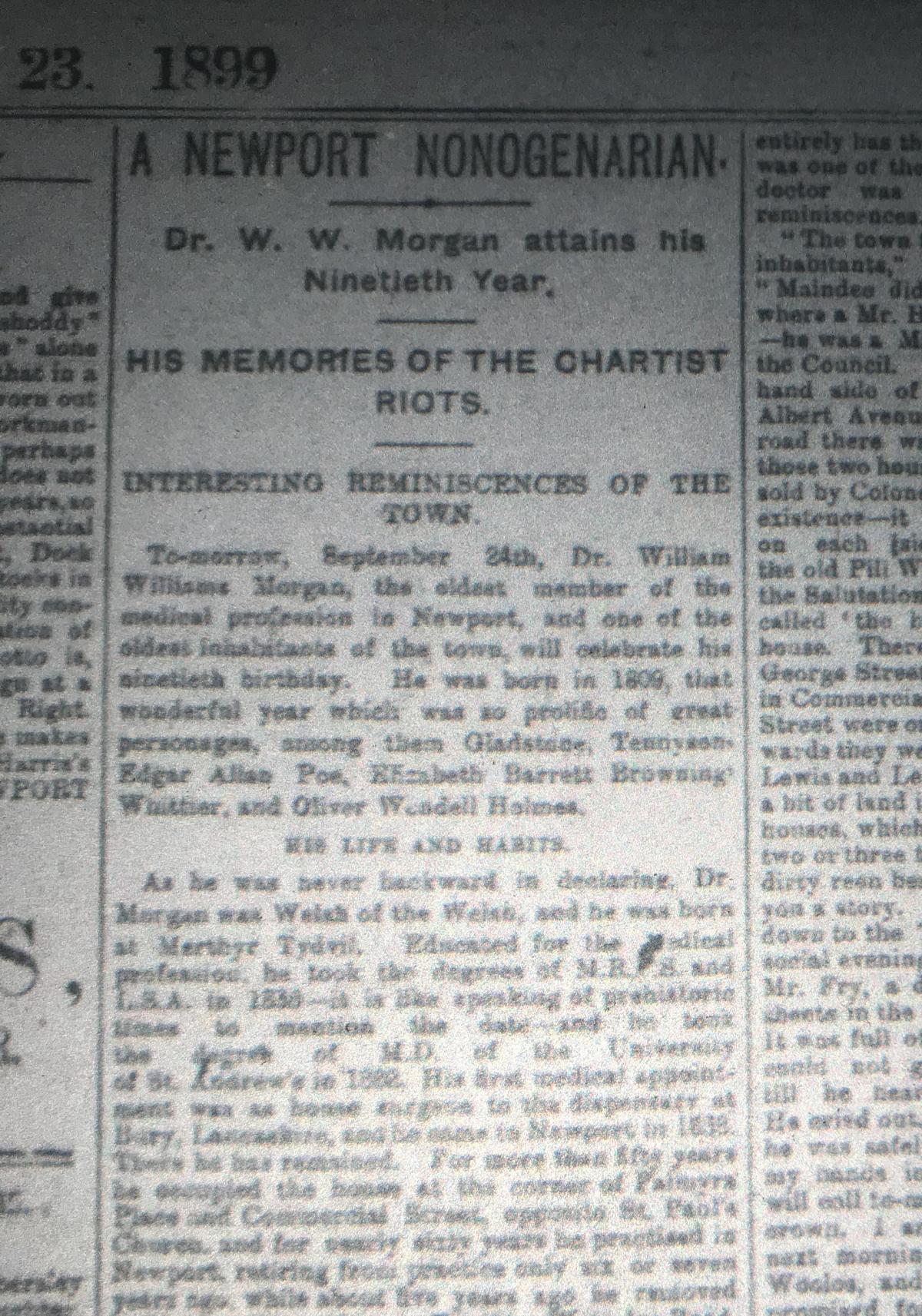

A DOCTOR who treated Chartists shot in the rising of 1839 recalled the events in the South Wales Argus in 1899. Former head of history at Caldicot Comprehensive School Peter Strong tells the story of Dr William Morgan.

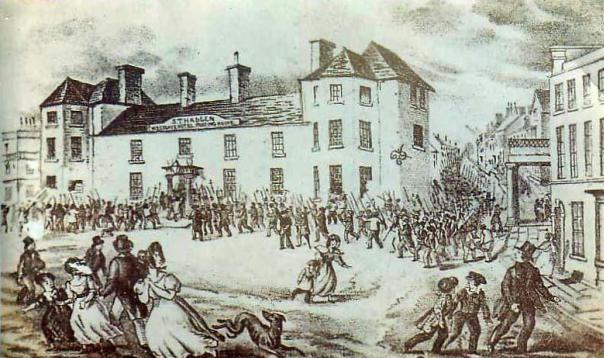

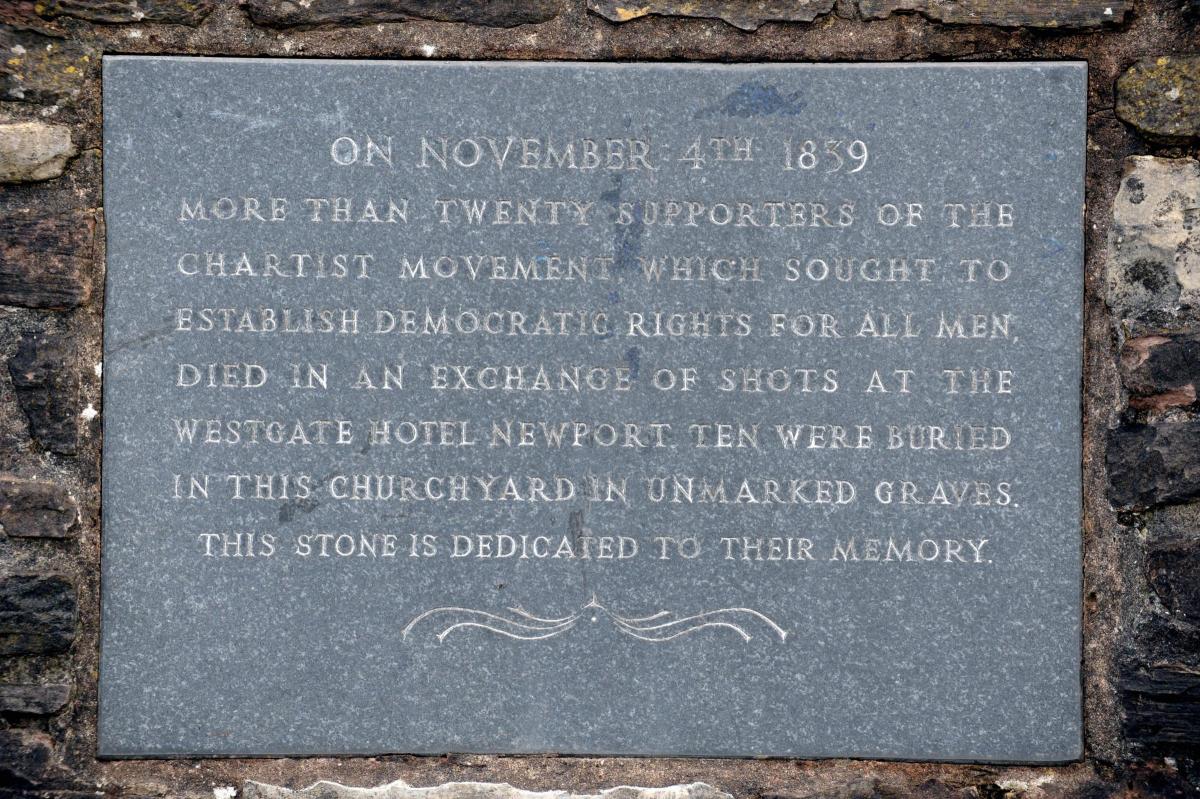

HE was an eye-witness to one of the most dramatic moments in Newport’s history. Thousands marched on Newport to press for political reform but 22 were shot down outside the Westgate Hotel.

The memories of Dr William Morgan brings to life that fateful day as he reached the end of his own.

On Dr Morgan’s 90th birthday he was visited at his home by a reporter and the result was a lengthy article in the South Wales Argus on September 23, 1899.

According to his own testimony, he came from a poor, although well connected, background. His father was a prominent Freemason in Merthyr; his maternal uncle was a surgeon with the army in India and another relative was physician at the London Hospital. His mother encouraged him to follow a medical career and after schooling at Neuadd Llwyd Divinity School for Independents near Aberaeron he did his medical training in London at Guy’s and the London Hospital. He served for several years as house surgeon in Bury, Lancashire before coming to Newport.

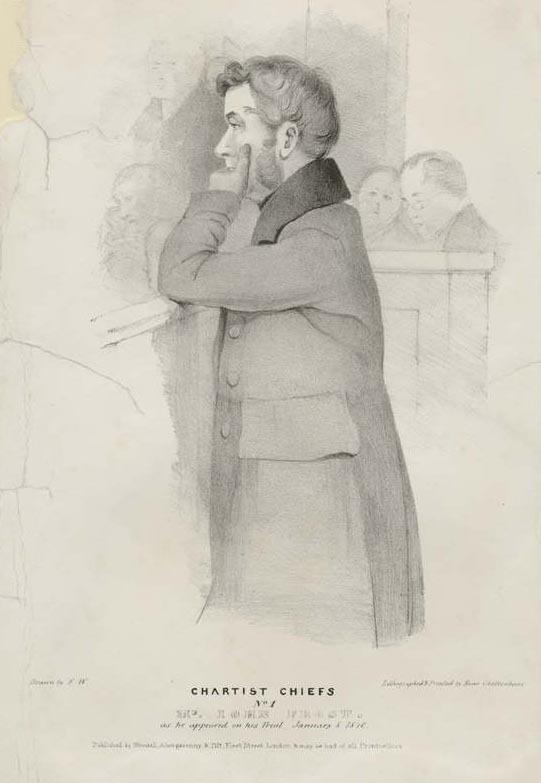

In his younger days Dr Morgan had been a ‘warm Liberal’ and upon moving to Newport had quickly become acquainted with the town’s leading political figures, including John Frost, who he describes as “a man of medium height, fresh complexion and nice looking, a man of great ability and considerable education. He was not at all the man who suggested the bloodthirsty agitator or rebel – there was nothing of the savage or the brute about him, but he was hot-headed and a Radical at a time when the term Radical was an opprobrious epithet. His great opponent was Mr Prothero, of the firm of Prothero and Phillips, who was a great power in the town.

They had been opposed to each other, writing pamphlets against each other on national as well as general politics, for John Frost was leader of the advanced party, while Prothero represented the old order. Frost was not a man of blood but he was a man of great force and character, and very popular with the people.”

On the evening before the attack on the Westgate, Dr Morgan had had his own encounter with the Chartists in the valleys:

“The day before the Chartists came to Newport I had been up to the hills to visit some patients … and as I returned I saw band after band of men coming towards Newport. I knew that they were expected, and I determined to ride into Newport, and give warning that they were gathering in force. As I rode, stones were thrown at me several times, but I took no notice. As I came nearer to Newport … I saw a man come out of a lane carrying a gun. ‘What are you going to do with that gun?’ I asked. ‘Nothing,’ he replied. ‘Give it to me,’ I said, and he did so. I fired it off and then took out my pocket knife, unscrewed the lock and put it in my pocket. I gave him back the gun, saying, ‘I am Doctor William Morgan of Newport. If you come to Newport and ask me for the lock, I will give it to you; but at any rate you won’t be able to do any mischief now.”

It seems curious that an armed Chartist should have such remarkable respect for authority and that Dr Morgan was lucky to reach the age of 35, let alone 95!

He continued: “When I fired the gun my horse ran away and I should have had to walk all the way to Newport, only it was seen galloping along the road and was stopped, I think it was at Risca. Then I rode into town, and informed the authorities what I had seen.”

On the day of the attack he was in the thick of it again: “The next morning I had to go out into the country again. I lived in a house at the corner of Corn Street, but I kept my horse at the Tredegar Arms, and I went up to get it. I found all the doors barricaded and although they let me in, they did not want to let me out.

“While I was there, firing was heard, and I saw a man wearing his carpenter’s apron go by…. I noticed that the man looked somewhat white, and that he staggered as he walked. I asked him if he was hurt, and he said he had been shot in the stomach. I examined him and tried to find the bullet, but could not, and the man was sent home.

“Then I went down to Westgate Square.

“The square was empty, but people were peeping around corners. I could see the barrels of the soldiers’ muskets pointing out of the windows, and I could see also a poor fellow lying in the road. He tried to rise himself twice, but fell back each time.

“I called out to some of the men, ‘He is wounded, help me carry him to a place where he can be attended to, but not one of them would move, so I went forward myself, signalling with my hand that my intentions were peaceable.

“I knelt beside the poor fellow, and finding that he was badly wounded, asked him if there was anything I could do for him. ‘Water,’ he gasped, and with that he died before my eyes.

“There was nothing to be done, so I left the body where it lay.

“Afterwards, I heard that there was a man up Water’s Court who had his arm broken with a bullet. I went up and found the man there.

“He said he was going to the post-office to post letters, when he was hit by a bullet from the hotel.

“The houses in Water’s Court were very poor, and I suggested that the man should be removed so that he could be properly attended to; but when we tried to move him we found that he had a long sword down his trousers leg.

“‘You hypocrite,’ I said, ‘pretending you were going to the post-office with letters when you had a murderous weapon down your leg. I’ll have nothing to do with you.’ I left him and he afterwards had his arm amputated.

It seems that Dr Morgan had rather forgotten his Hippocratic oath. Nevertheless, it appears that the man survived for many years to come:

“For years after, there was a one-armed man who drove the water cart – the town and the shipping were supplied by water cart in those days - that was the man.”

This is confirmed through an interview with an elderly resident of Newport published in the Weekly Argus on 27th December 1924, who named him as Ben Davies.

Dr Morgan concluded: “That is all I know about the Chartists riots, except this: twelve months afterwards, a man came to me, and asked for the lock of his gun, which he said I promised he should have when he liked to claim it; and about the same time a constable said to me, ‘You don’t know how near you were to being shot that morning in front of the Westgate.

“When you came forward the sergeant said to Lieutenant Gray, “Shall we fire?” and I said, “Don’t shoot! That’s a young doctor who has not long come to the town.”

Of course, they might easily have thought that my signals were signals calling on Chartist companions to make an assault upon the hotel.

“There is just one other thing.

“During the firing, a bullet went through the window of my house on Corn Street, passed through a door, and stuck in the wall.

“I was not in the house at the time, but I had the bullet and for many years I preserved it.”

Dr Morgan’s comments on his narrow escape from being shot suggest that even some time after the firing stopped the situation was still sufficiently ongoing for it to appear to the soldiers that a fresh assault on the Westgate might be about to start.

“If this is so, it indicates that the Chartists did not turn and flee as rapidly as some accounts suggest.

Dr Morgan went on to become a leading citizen of the town.

He remained active in politics, initially as a Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist, and stayed in Newport after retirement, living at Penrhiw, Waterloo Road, on the edge of Belle Vue Park.

He died in January 1905 and in his obituary in The Times, readers were told he was “probably the oldest medical practitioner in the country, at the age of 95”.

His death probably meant that the Newport Rising had finally passed from living memory.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel