RETIRED Metropolitian police inspector-turned author Martyn Parfitt, 55, witnessed horrific scenes in the aftermath of London terrorist attacks during a career spanning almost 20 years.

Speaking from his home in Monmouthshire, he told KATH SKELLON about the moment the bombs exploded and chaos shook the city.

“It was July 1982. I was 25 and working in the CID Crime Squad at Kentish Town police station in north London when something happened that would change the course of my life.

We were the first on the scene of the Regent’s Park bomb explosion, two hours after a similar attack at Hyde Park.

A bomb hidden underneath the bandstand exploded during a performance of music by the Royal Green Jackets band to a crowd of 120 people. It sounded like fireworks and everything around me shook.

It was laced with six-inch nails, causing dozens of serious injuries among the audience and instantly killing seven band members. It was carnage.

I had no sense of direction and the sound hit the air around us even though we were over a mile away. We drove in the direction of where we thought something had happened and listened to the radio. It was the first time I heard an explosion and not the last.

Being in plain clothes made it almost impossible to be recognised as a police officer, so despite trying to help and administer first aid, my colleague and I had a lot of problems with fellow officers who thought we were just busybodies getting involved. Some people were so badly injured there was nothing we could do.

The events of that day left me feeling uncomfortable working in central London so my love of motorbikes drew me towards the traffic unit at Chadwell Heath, Essex, where I took my advanced car course and was eventually posted back to central London at Euston Traffic Unit.

On April 17, 1984, I was driving a marked traffic car when word came over the radio of a shooting in St James Square outside the Libyan Embassy.

Our car was sent to escort an ambulance with an injured officer to get it to a hospital.

The traffic was a nightmare.

The roads were chaos and blocked up. We were forced to drive on pavements, between bus stops and shop fronts and to direct vehicles out of the way so that we could get to the hospital as soon as we could.

It was a tortuous drive.

As I got to the hospital I knew we had done our best.

But when the ambulance crew brought out the officer we knew from their body language that it was too late.

What I had no idea of at the time was that it was my friend, PC Yvonne Fletcher. She had been at my home only two weeks previously.

I only found out when I arrived home that night and saw it on the news.

My first brush with death came two years later when I was riding a police bike and a car pulled out in front of me, throwing me into the air. I landed on the road in front of a bus. I was knocked out and came to in the road looking up at the front of the bus. I thought I was OK until I went to get up and realised I couldn’t move for the pain. I had suffered broken ribs, but felt lucky and grateful to the bus driver, who reacted quickly and stopped in time.

I was promoted to sergeant later that year when the Tottenham riots kicked off.

Several of my PCs were taken off my shift at Barnet police station and sent to Tottenham to help. When they returned they were changed men, having tried to save a fatally injured colleague.

The death of a colleague is very hard to come to terms with. I’ve seen several officers suffer from post-traumatic stress. Now, years later, I look back with regret that I didn’t understand what had happened to them and wasn’t able to help.

After rising up the ranks to inspector I found myself at Stoke Newington, running the busiest station in the UK.

Known locally as Fort Apache, it was one of the most exciting places I had ever worked. There were murders, shootings, fights, armed robberies.

In 1993, during the late shift, I was sent to a bomb threat with the chief inspector at the London Stock Exchange and was cordoning off the area when News of the World journalist Ed Henty tried to get past the cordon. We turned him away but I think he may have got in without us seeing.

He was killed by the explosion.

We heard an awful sound like scaffolding falling, or a train crashing. It was the loudest thing I have ever heard.

A shockwave came around the streets and blew us off our feet. All the shop windows went in. We were OK, so we headed towards the scene of the explosion and were faced with indescribable damage and complete devastation.

A PC from my shift was kneeling over the body of a young girl in a complete state of shock. To this day I don’t know what he was doing there or how he got there, as he was well off his posted ground.

After that I can remember little of that night. I got home in the early hours feeling powerless and frustrated that we had failed to save a girl’s life and puzzled as to how she came to be in the street that was cordoned off.

I put the incident behind me but was reminded of her a few years later when I attended a suspicious death. It was a party at a five-floor house with a roof garden. A girl had sat on the wall on the roof and fallen off. She was only about 20. When I saw the ambulance crew working on her I pictured the girl from the bombing.

She also died.

After seeing the parents at the hospital I went back to my office, closed the door and cried.

Not long after I began to suffer flashbacks and nightmares about the bombing and eventually retired from the force suffering post-traumatic stress disorder.

It wasn’t all bad or high drama. I have happy memories of seeing Prince Charles and the late Princess Diana riding in the royal carriage on their wedding day. We were on duty as crowd control but of course you couldn’t resist turning around to watch them as they passed by.

On another occasion I delivered a baby at a house in Stoke Newington because there was no ambulance available. There was no time for towels or hot water, the baby fell into my hands and I passed it to the mother – it’s something that stays with me forever.

As a teenager I hadn’t intended to join the police. I grew up in Middlesex, and as a student, played guitar in a band where we held auditions and turned away a thenunknown Simon Le Bon, who later formed Duran Duran.

After leaving school I served for a short time with the Royal Artillery but an ankle injury while on an assault course saw me medically discharged.

A friend of mine joined the Met as a PC and I ended up joining, becoming the top student on my intake.

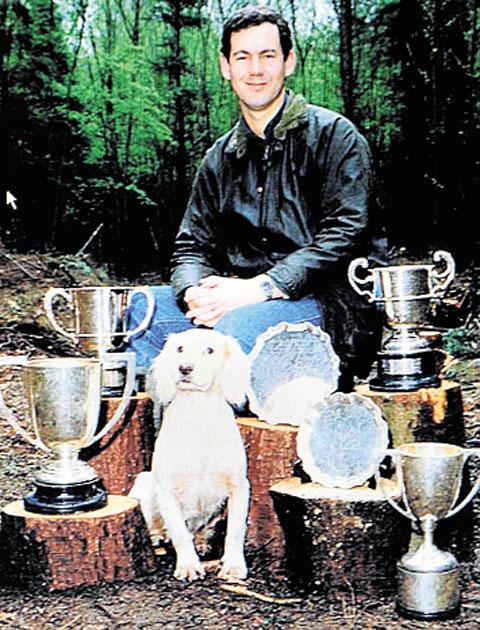

My mum hails from Swansea and this played a part in me relocating to Hollybush, near Blackwood, 15 years ago. My then wife, Sue, and I found a smallholding and took over boarding kennels that took in strays from two authorities. We campaigned to change the policy that stray animals were put down and got the Dogs Trust involved in educating people to try to reduce the number of stray dogs and unwanted puppies.

Over 15 years we cared for and rehabilitated more than 6,000 dogs and cats at our own expense.

Even though I moved to Raglan in November, I still have strong ties with the Sirhowy Valley and care about the community.

I am still a member of Hollybush village residents’ association, sit on Argoed Community Council and am chairman of governors at Oakdale Comprehensive School.

In 2009 I became the first former police officer to sit as a magistrate in Gwent.

My life in the Monmouthshire countryside, living in a converted barn with four dogs is very different from the fast pace of London. When I am not carrying out my various roles I immerse myself in my passion for writing and keep bees.

I have been able to use my experiences in the force and focus on using them to write my first novel, recently released on Kindle.

I’ve been shocked at the response to Wicked Game, written under the pseudonym Matt Johnson, which reached number seven in the top 100 Kindle bestsellers list and had 10,000 downloads in 12 weeks, to be published in paperback in July.

It’s set in London and tells the story of former SAS and now royalty protection officer Robert Finlay, who opts to transfer to a local police station.

He is approached by MI5, who tell him that two former army colleagues have been assassinated in different parts of the world, drawing him into the fight against terrorism.

Writing has been a cathartic experience for me. I’ve had such a good response to the book, which is dedicated to four late colleagues, that I’m now working on a sequel."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel