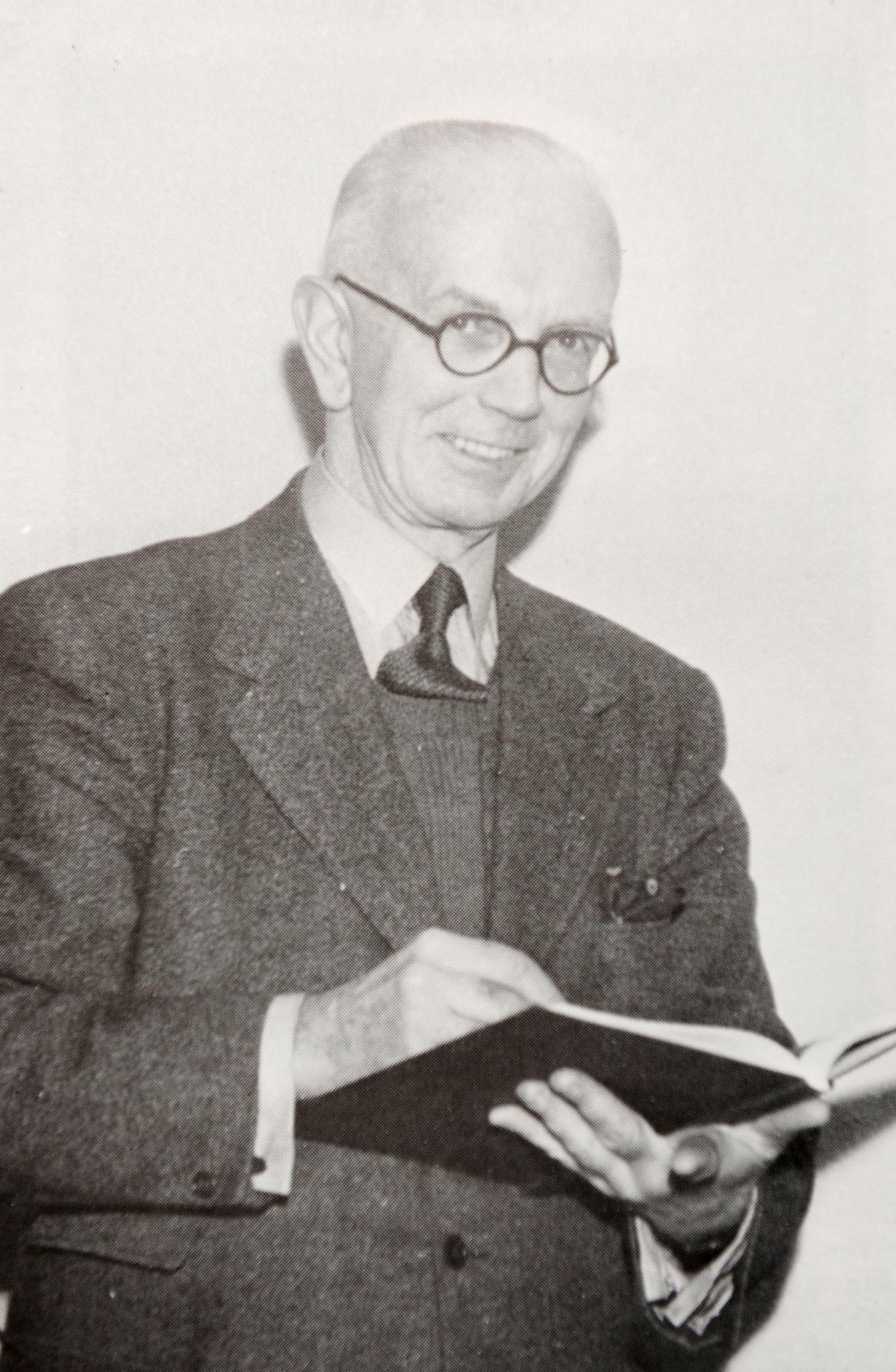

He was a writer, artist and renowned Newport headmaster who wrote more than 800 articles in the South Wales Argus and several books about his beloved Gwent.

UNDER the title ‘Rambles in Gwent’ he delighted readers with his weekly column, telling of the history of some unexplored corner of the county.

He continued writing for the Argus until 1970, just four weeks before he died.

From today, we will publish his columns again, giving you the chance to enjoy his evocative prose which captured, as an Argus editor, Kenneth Loveland, said: “The shy beauty of this delectable county”.

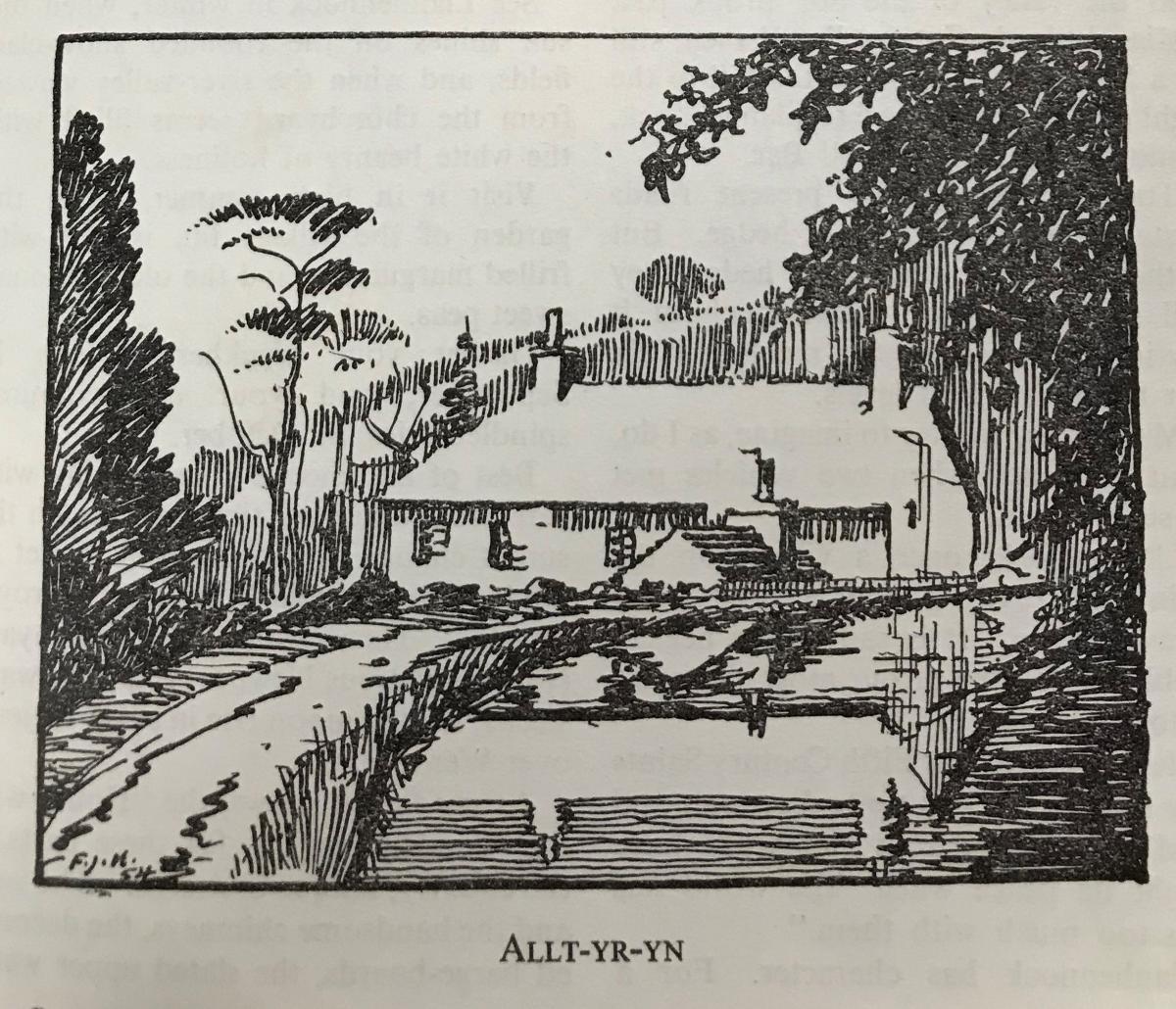

We begin with a piece written in the early 1950s on Allt-yr-yn.

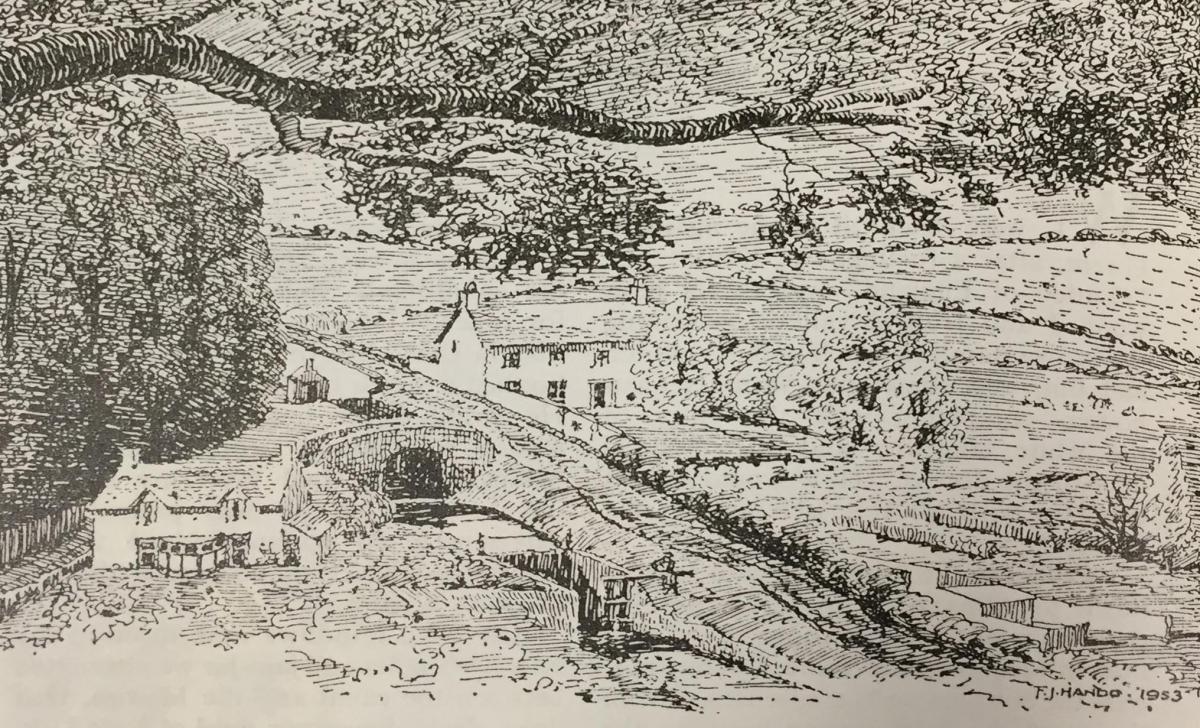

WE were back at home again in Gwent, after a fortnight in Kent. The Garden of England” was at its best, wooded and fruitful valleys enshrining the brown hamlets –each with its church and inn, and sometimes with its oast-houses – competing with the glory of the white coastline and the graceful lines of the downs.

How would Gwent compare with all this rich and varied beauty? I walked to the top of the path leading down to Allt-yr-yn. In fitful sunshine the ribbon of the canal shone in the sky-hues of turquoise and white.

White also were the cottages and farmhouses. From the canal the fields swung away to the Henllys woodlands, each field beautifully rounded. Over the woods, from the pale blue of the reservoirs past Castell-y-Bwch to the Eastern Valley, my eyes followed with satisfaction the lines of the foothills, while in imagination I sensed the scent of the honeysuckle in the lanes, and of the damp earth in the fields.

Over all, grey suffusing the green, arose in nobility our own mountain. Perfect in its smooth and suave con-formation, changing in colour as the cloud-shadows flew eastwards, it crowned the gracious landscape with majesty. Twyn Barllwm and “Little Switzerland” had again, as after so many previous holidays out of Gwent, filled my soul with home-coming pride and satisfaction.

Memory began its magic. I saw myself as a very small boy sitting on the canal-bank while my father fished for roach. Usually he caught gudgeon, but on those halcyon evenings when he hooked a roach he became transformed.

He could never hope to rival Ridd, whose four-pound trout, caught in Malpas Brook, had fired my father’s imagination, but he was patient and determined, so patient indeed that I determined never to become a disciple of Izaak Walton.

Allt-yr-yn minnows were more in my line. With net and jam-jar we alternated between the canal and the Muxon, that deep, dark, dangerous pool at East Usk.

Then, somewhere around the age of eight, it became necessary to swim. How can I recall for you the bliss of those sunny summers in the canal near Allt-yr-yn? The field below the Barracks (it is called in Thorpe’s Survey of 1753 the “Hanging Field”) falls steeply and then flattens into a gentle slope.

Here a dozen little boys, who had walked all the way from Maindee, would strip, climb the meadow, race down the slope whooping like Sioux, and plunge into the cool water. Somehow, dog-paddling at first, we learnt to swim, and then we essayed diving from the lock-gates. There was, I remember well, an especial taste, an individual flavour, a unique bouquet, in the canal water.

It was compounded of rotting wood, of green water weeds ; there was a suspicion of stagnation ; there were dark rumours of dead animals floating in upper reaches of the canal ; and the “floor,” when we used it, was very soft and black, “like the inside of a black blanc-mange.”

The weeds were a nuisance. At intervals, however, a heaven-sent official would clear the water, and the weed would then lie for some days on the bank, adding to the elysian odours, but as the piles of weed interfered with the tow-ropes of the barges, they were not allowed to remain indefinitely, like the weed-piles on the banks of the reens.

The school which I attended was visited by an art master, who knew more about his subject than he knew about boys. He persuaded the headmaster to allow him to take us to Allt-yr-yn for a lesson in “sketching from nature.” Sixty boys disappeared during the journey, and none of them returned with a sketch. No comment was made by the headmaster, but the project was never repeated. Later in life, when my eyes were opened, I fell in love with Allt-yr-yn. In part it was due to WH Davies, who saw the waters of Alt-yr-yn shining brightly through his tears; in part it was due to my artistic awakening, for the French Impressionists had cleaned up our palettes and taught us that the most important object in a picture is light!

Surely this is nowhere more evident than in this view of Allt-yr-yn! The next time, therefore, that you visit the “Double View,” go in the morning, when you may see Henllys Church and many another gem which is hidden in later light. Do not listen to those who tell you that the Sugar Loaf is visible; the solitary peak is the Skirrid. Listen neither to the wag who is fond of announcing, “Yes sir. Those are the reservoirs of Ynys-y-Fro : one for hot water, one for cold.”

And when you have taken your fill of that view, stroll down Barrack Lane—that prehistoric track, which was very old when the Second Augustan Legion marched westward—and feast your eyes on the more intimate loveliness of the view over Allt-yr-yn.

Footnote.—”Allt-yr-yn” implies the declivity of the ash trees. My Welsh friends wish to preserve the correct pronunciation of “Allt,” but I fear that “Alter-e’en” – as WH Davies pronounced it – has come to stay.

Next week we journey with Fred to Llanhennock, a village “of character” where he shows us their “treasured relic – a house with a wooden leg”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel