THE life of a wartime RAF bomber crew could be brutally short, with crews suffering a 50 per cent casualty rate – Ralph Cooke found this out very quickly.

A curious feature of Bomber Command life was the way crews were formed. New recruits would mingle informally with existing teams who had a vacancy. If they liked the new recruit, they would ask him to join them.

This is how Air Engineer Ralph found his first crew. He took a liking to a team of New Zealanders and begged to join them. Their skipper, Flying Officer Russell wanted Ralph to join them. Both pleaded for this to happen but were refused and Ralph was assigned to another. They flew on their next mission but never came back.

After this, Ralph never questioned an order or decision. He believed from then on that fate should be allowed to take its course. But he was to have many brushes with fate in his RAF career.

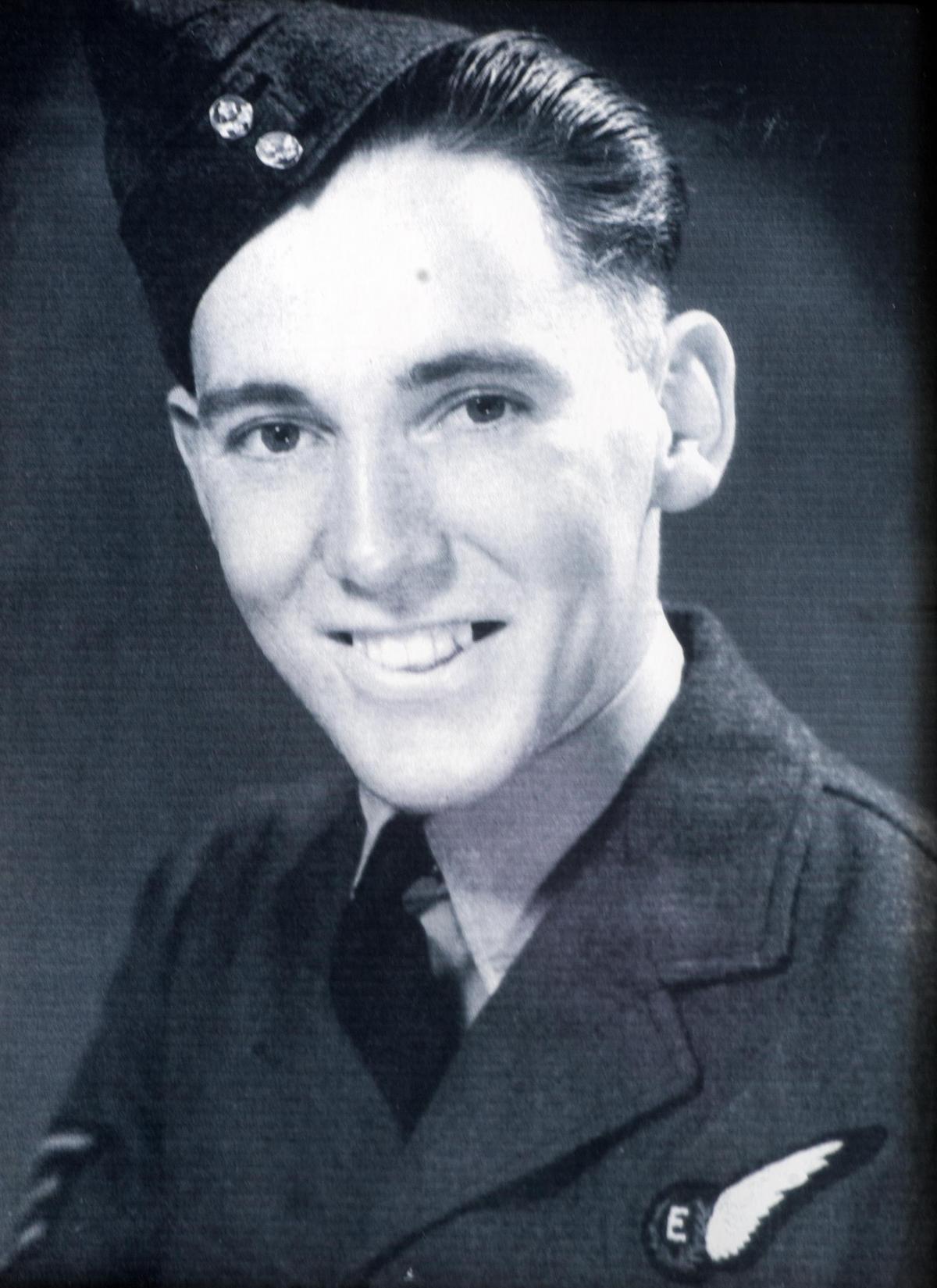

But to begin with fate threw up many incongruous scenes. Ralph saw this early on when after joining-up in 1943, aged 22, he was ordered to muster at Lords cricket ground. The new recruits were given their meals at London Zoo. Ralph did his basic training at Torquay in September that year. Here, aside from learning to march and about the basics of military life, he had to dive off the pier to learn how to survive at sea.

He then went to RAF St Athan for engineering training. After this he was posted to 57 Squadron based at East Kirby in Yorkshire. He later served with 189 Squadron.

His first mission was to Darmstadt on 25 August 1944. Their second saw them fly for 11 hours to bomb the city of Konigsberg in the Eastern Baltic.

His most dangerous mission was over Helibron on December 4 1944. He told as they were running up to the target the rear gunner reported a Junkers 88 on their tail 'and closing'. There was no room to manoeuvre but the skipper was determined to press on with the attack. Ralph said in his log: "There seemed little possibility we might survive." The night-fighter had better weapons. Ralph and his crew-mates saw green tracer whizz past, but miraculously he missed.

The rear gunner opened fire with his four Browning machine guns and hit him.

However, their perilous mission was not over. As they returned, they found the bomb doors had been closed too soon and that one of their bombs had not been dropped. Rather than take the chance of landing with it onboard, they managed to ditch it over the North Sea.

Every day, they would look at the crew list to see who would be sent on a bombing mission and be 'dicing with death' that day. With each raid they felt the odds on survival shrinking. But still the taskings came.

Another long-range mission saw them fly to Stettin in the Baltic on December 28 1944 to bomb the cruiser Köln. The last day of 1944 saw them attack German troop concentrations during the Battle of the Bulge.

By February 1 having flown their 30th mission, the crew had black news. The number of missions they would need to complete was raised from 32 to 36. They would have to fly on and brave the steepening odds against survival.

The risks they faced were not just the German night-fighters or anti-aircraft guns. Ralph remembered one raid when over the target another Lancaster above them opened its bomb doors, unaware that one of its own was flying directly underneath. A sharp-eyed crew member spotted it and yelled 'corkscrew' - an order to turn sharply, normally used to evade night-fighters. They narrowly escaped.

When asked if he was ever frightened, Ralph recalled that he only became apprehensive when coming back from a raid; for then the Germans would know where you were and would be after you. Again, it was often not the enemy Ralph had to fear when flying back from one raid. He noticed the bomber descending and looked over at the flight deck and saw to his horror that the pilot had fallen asleep. Ralph could merely shout: "Up, up, up!" Thankfully the pilot started awake and climbed steeply away from the ground.

Their 32nd mission was to bomb an oil refinery at Lutzkendorf on 14 March 1945. They came home safely knowing they still had four missions left. Allied forces occupied much of Nazi Germany by this point but they were not yet beaten.

By 9 April, Bomber Command again changed the required number of missions, but this time they were cut to 33. Ralph's crew nervously eyed their final mission. Would they survive one last haul into the hostile skies over Germany?

As they prepared grimly for their final flight, a further order came through on 18 April. Bomber crews would now only need to fly 30 missions. This they had done. As they had already flown 32 missions, they had officially finished their tour.

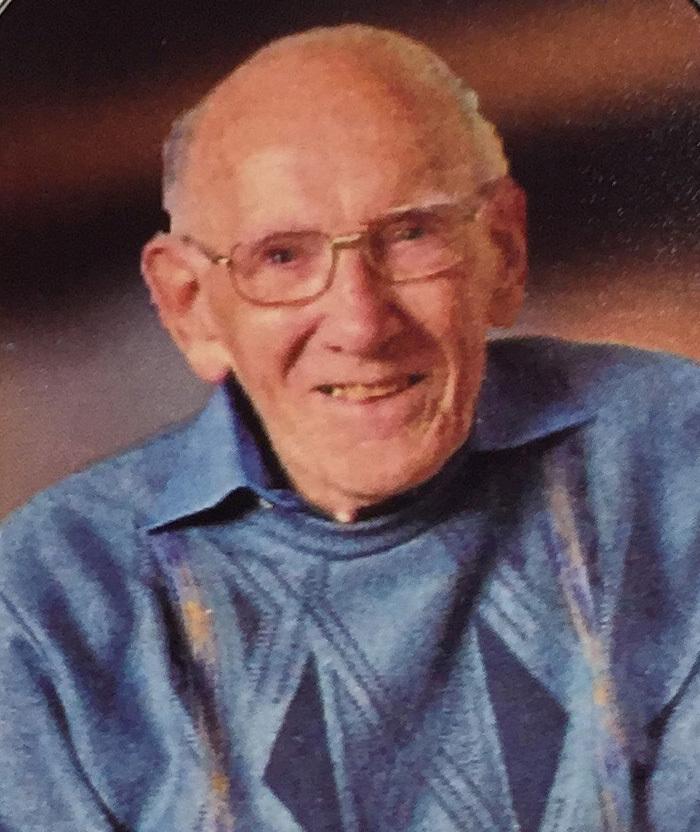

His widow Dorothy says that Ralph always thought he was lucky. "He said 'there was someone looking after us' because they had so many near-misses."

The luck stayed with him long after the war ended when he narrowly escaped being crushed by a car his daughter Helen recalls.

Ralph didn't like the fact that Bomber Command was ignored after the war. In a speech after VE Day, Churchill made no mention of the part they played in defeating Germany. This was compounded when they were denied a campaign medal.

Helen recalls: "He always said 'if Britain hadn't bombed Germany we would have lost the war'".

When the bravery of bomber crews was finally recognised with the unveiling of a memorial to Bomber Command in London, Ralph said it was "too late" for the crews.

Many of the skills which served him well in Bomber Command served him well in later life. The meticulous eye which would monitor a Lancaster's fuel on a bombing raid was used for peaceful pursuits after the war's end.

He made Helen a kite out of the silk from his parachute. She recalls: "It was a proper diamond shape and the reel was taken from a fishing rod”. She says: “If he couldn't mend something, he'd make a tool so he could do it," adding: "he was an expert at everything he did".

At Ralph’s funeral, his grandson Nick told how his talented grandfather made a chair which had seated three generations and "the toys which kept us children quiet", before adding "his tools can now be passed on to us".

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel