When the verger of St Margaret's church in Blackwood, George Glastonbury, rings its bell each Sunday, there is one soldier in particular for whom it tolls.

James Herbert Spencer was a miner from the town who went to war with the Monmouthshire Regiment in 1914. He was selected, as were many Gwent miners, for his skill at working underground to serve in a dangerous but brutally effective form of warfare.

In peacetime, the miners’ aim is to bring coal to the surface so that people can have heat and light and industry’s wheels can turn. In wartime their skill delivered death.

The bell inscribed in his memory is testament to the dangers these soldier-miners faced and which ultimately killed him.

By November 1914 the war on the Western Front was bogged down into siege conditions. Just as sieges had been broken since ancient times, both sides rediscovered the art of tunnelling under enemy positions and detonating explosive to destroy them.

One of the first Gwent miners who fought below ground was Captain Arthur H Edwards of Blaenavon.He was a mining engineer and Territorial officer with the 2nd Monmouthshires in 1908. With the outbreak of war he led a detachment from the Battalion for mining operations. His group was responsible for laying and blowing the first mine of the war at Le Touquet in 1915, for which he was awarded the Military Cross.

His citation shows how miners would not only face the risks of tunnel collapse or asphyxiation. As they dug under an enemy position, the Germans were digging too and broke through into the British tunnels. A fierce under-ground hand to hand fight ensued, in which it tells us “the Germans were eventually worsted”.

Brutal though this operation was, it was small beer compared to those which would follow later. The technique was employed to more lethal effect at Ypres – and men from the Monmouthshires, including Sgt Spencer were at the heart of this operation.

Hill 60 was so called because it stood 60 metres above sea level. On the very flat Flanders plain, that height is worth fighting for and from the earliest months of the war it had been fiercely contested.

The men from the Monmouthshires, now part of the 171st Tunnelling Company were set to work digging three tunnels from their lines, through the spoil heap and under German lines 100 yards away.

The site was littered with the dead which had been left to rot in this contested no man's land and men often had to remove decomposing bodies as they dug. Digging in heavy clay was tough work. Despite wooden shuttering, it oozed through gaps.

The tunnels were small, some only three feet high by two feet wide. Ventilation was a problem too. Fans were too loud, so blacksmith’s bellows had to used. Candles would barely burn.

To guard against German counter-mining men would have to listen carefully in the dank tunnels. One of the miners, Lance Corporal Robert Leonard of 3rd Mons was one of many who did this by crouching in a small shaft with a stick thrust into the ground - the free end of which he clenched in his teeth. Unsurprisingly this was not effective as any vibrations from tunnelling were masked by the tremors from continual shelling.

Work had to be carried out in an "uncanny silence". The debris from the face of the 'sap' as they were called was placed carefully in sandbags and loaded on small trolleys, which were worked back noiselessly over wooden rails to the bottom of the shaft. The bags were then used to repair trenches.

When they emerged from eight hours of digging, soaked in sweat and muddy water, there was no change of clothes but they would get a much appreciated tot of rum. This they would do for stretches of six to nine days.

By the 10th April the tunnels had reached the German lines. One tunneller described it as "the most exciting period of my life coupled with anxiety".

The men carefully laid almost 6,000lb of gunpowder. They had to carry this under constant shellfire. The Regimental history noted grimly: “The officers carried the detonators in their pockets, and the men the explosives on their shoulders. One mishap, and we should all be hurled to eternity."

The men had undergone great risk to dig the tunnels which could not be wasted. Cabling to detonators was duplicated, but more risks loomed. The men were suspicious that the Germans were tunnelling near one of the British chambers. On April 2nd they seemed so close it was feared the Germans may break into the British tunnel at any time. A small charge was laid to blow up the German tunnel if they broke through.

Sandbags were placed around the charges placed to increase the upward blast. There were suspicions that the Germans might be about to blow their mine under the British lines – so the race was on.

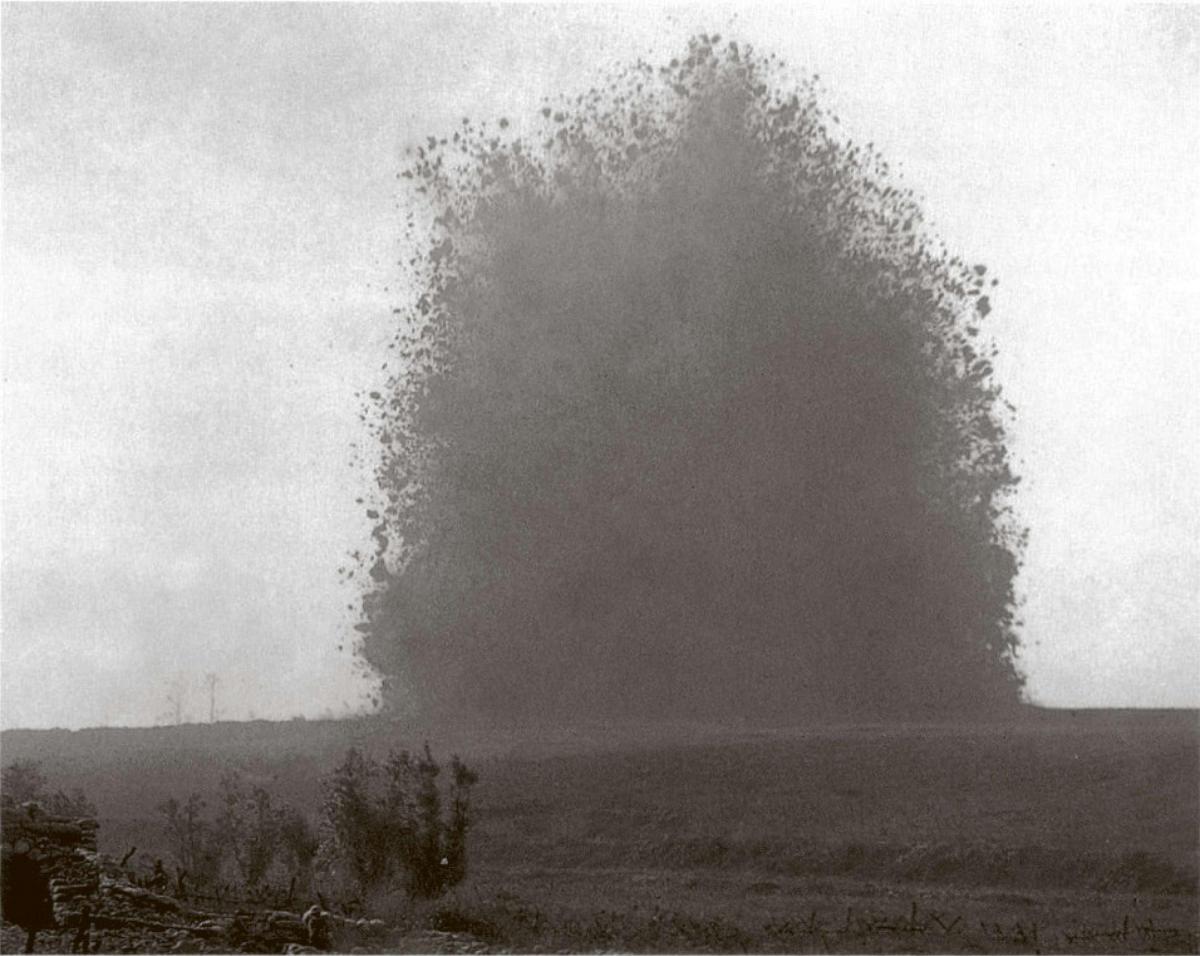

In very fine and clear weather, at precisely 7pm on 17th April, 6,000lb of gunpowder exploded, spewing debris over 300 feet into the air and for over 300 yards around.

British troops charged the German positions but met scarcely any opposition. The German lines had been obliterated. It had taken around two minutes to capture the hill at a cost of seven British casualties. The history noted “the success of the mines unquestionable."

The craters were up to 90 feet across by 30 feet deep and were still visible in 1925 when the writer of the regimental history visited.

Although casualties were slight, Hill 60 was to claim a British victim soon after in the vicious game of counter-mining.

Sgt Spencer was in charge of a party working at the trenches when the Germans blew up the neighbouring British tunnel, burying one man and partly burying another. Braving the poisonous gas that filled the chamber, Sgt Spencer went down to haul them out. He was overcome by the fumes and when he was brought out he was dead. His commanding officer, Capt E. Wellesley, consoled Sgt Spencer’s mother with the assurance that he “was always conspicuous in the trenches for his zealousness and he met his end fearlessly and doing his duty as a soldier should.”

Perhaps in recognition of the particular kind of hell the soldier-miner had to endure and the selfless way he met his end, people who knew much about the risks of work underground paid to have a bell cast in his honour, inscribed with the words:

‘To The Glory Of God In Memory Of Sergt. J.H. Spencer, Who Was Gassed At Hill 60, France, June 2nd 1915, When Nobly Attempting To Save A Comrade’

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here