IT WAS Newport’s blackest day of the war. No town in Wales suffered a blow like it, or has done since. Barely a street was untouched by dreadful news as Newport’s own soldiery, the 1st Battalion the Monmouthshire Regiment, was almost wiped out.

In the days after the bloody battle, doors would be knocked on Clarence Place, Queens Hill, Llanwern Street, Stow Hill and more, bringing terrible news.

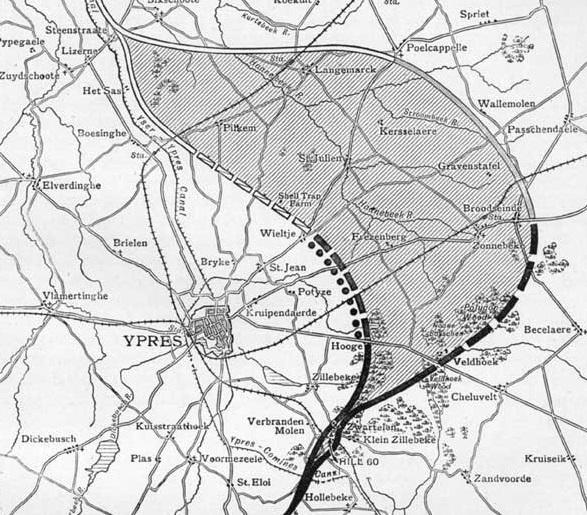

The Germans saw the bulge in the allied front near the Belgian town of Ypres as a weak point in their chain of trenches. If the Germans broke through here, they could swoop on the channel ports and invade Britain. They had launched attacks on April 22, and by the night of the May 7, all three Monmouthshire battalions were in line together. The 1st Battalion at Frezenberg, the 2nd to the north and 3rd to the south.

The British were badly exposed on the downward-sloping Frezenberg Ridge and they were outnumbered by three or four to one. For every one gun the British had, the Germans had eight.

The shelling began at first light, and as Rifleman WA Rogers of A Company 1st Mons recalled: “They kept it up for 12 hours. There were quite a number killed and wounded by 10am. Shortly afterwards the Germans could be seen advancing.” Rifleman Jack Williams told how they were in “a perfect hell of lead and shrapnel for about six hours expecting every hour to be our last”.

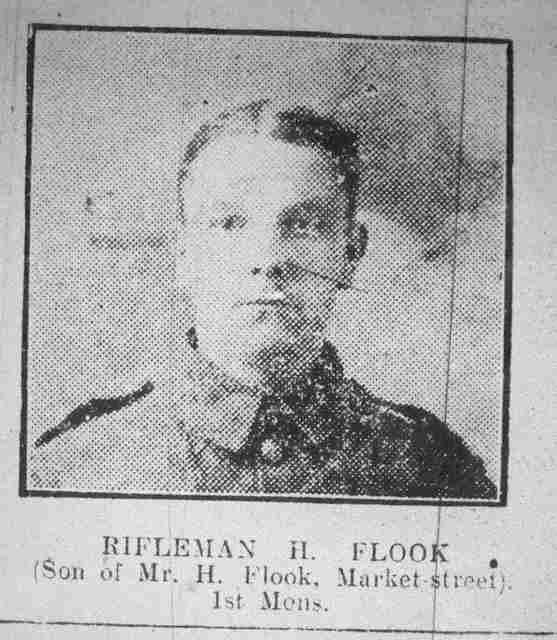

By noon, waves of advancing Germans threatened to break the British lines. Lance Corporal Henry Flook, son of one of the founders of Newport’s Indoor Market is said to have cried “fix bayonets and come on you lazy bastards” as he pushed the men to charge a machine gun post in the farmhouse pouring fire on the Monmouthshires. They silenced the machine guns, but LCpl Flook was later killed.

They were now unable to bring reinforcements due to shellfire, unable to manoeuvre under cover because the trenches were filling with the dead, and the German onslaught from two sides. The only choice seemed to be retreat or surrender.

As the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Robinson, tried to organise defence of the right flank, he was shot in the neck and killed.

Those who could, withdrew, but this was fraught with danger. Soldiers had to run across three or four fields under murderous rifle and shell fire. Rifleman Seary recalled: “Shells were falling every other yard – it seems a miracle I wasn’t hit.” He ran or crawled flat on his stomach for over an hour before he was safely out of range.

Bugler Stan Rowe saw a shell drop between him and a friend which “took a piece as big as my fist out of his back but did not touch me. I shall never forget the cry he gave,” he said.

Later, a British counter-attack forced the Germans to give up some ground they had won. They were forced to dig in 300 yards in front of what was left of the British positions, across three or four fields where Rifleman Seary had ran for his life. The stand put up by the 1st Mons had sapped some of the fight from the Germans.

Before Frezenberg the 1st Mons had 23 officers and 565 other ranks. As they counted the cost of battle, they found only three officers and 126 other ranks were able to answer roll call.

We might think that news from the front, particularly news as bad as this would not have got through or been thoroughly sanitised.

That is not how the Argus reported the battle over the days that followed the May 8.

There is scant mention on May 10, but as the week draws on the news comes through. By Tuesday headlines warned: “The Big Offensive – Monmouth’s in the thick of it – Terrible losses on both sides”.

On Wednesday, May 12, the Argus admitted: “If there is bad news to come, there is at least the mournful satisfaction that our brave boys have acquitted themselves like heroes.”

And bad news did come. The next day, May 13, the Argus noted the 3rd Mons too had suffered “terribly heavy losses”, being reduced to four officers and 130 men.

After earlier saying he was believed missing, Friday’s Argus carried news of official confirmation of the death of Harold Thorne Edwards. It said the family had received a message from the war office and a telegram from Lord Kitchener.

By the Saturday, the full horror was revealed. The mayor of Newport spoke of the “terrible gloom that had been cast on the town by the news that so many of our brave and gallant soldiers that have come out from Newport have now performed the greatest duty to their country.”

Few Newport streets were unaffected. Josiah and Jane Hyde of 54 Clarence Place, Newport, learned their son Rifleman George Harry Hyde had been killed. The Brown family of 22 Robert Street, would be told their son Bob Brown would not return; and Harry Flook of Queens Hill, Newport, would hear his son and namesake was dead. Mrs M Pope of 44 Llanwern Street too would hear the worst about her son Arthur John Pope.

There was one other piece of news the following Monday. One of the three surviving officers, Captain Oswald Williams had witnessed Captain Harold Thorne Edwards’ last ditch attempt to hold the right flank and stem the German advance.

His position seemed hopeless and news of his death had already come. But it was the manner of his going, which would inspire a memorial to that grim day after the war.

Capt Williams told the Argus how Edwards and his men were surrounded as they tried to form a defensive line.

Williams said: “When called upon by the advancing Germans to surrender, Edwards said: ‘Surrender be damned’, and was seen firing at the enemy. He was then shot – and the men reported – killed.”

It was a phrase that rang with defiance and gave some comfort to readers that the 1st Mons had gone down fighting. Between the wars, the South Wales Argus commissioned artist Fred Roe to paint a picture of that harrowing day. It shows Captain Edwards, revolver drawn and defiant, surrounded by his men of the 1st Monmouthshires.

Newport continued to honour its fallen from that bloody battle. Eight may trees were planted in Belle Vue Park as a touching reminder of this now resonant number and how it told of unspeakable horror. and now, a hundred years later, eight may trees stand again at Blaina Wharf in Newport in silent tribute to those men from Newport who died on that blackest of days.

Acknowledgements:

Shaun McGuire www.newportsdead.shaunmcguire.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel