INTERNATIONAL athletics and cycling stars competing in a brand new stadium and velodrome in Newport, road cycling at Tredegar Park, lawn bowls in Ebbw Vale, shooting in Blackwood and weightlifting at the Celtic Manor.

This is what we could have been looking forward to if the Welsh Government had decided to go ahead with a bid to host the 2026 Commonwealth Games.

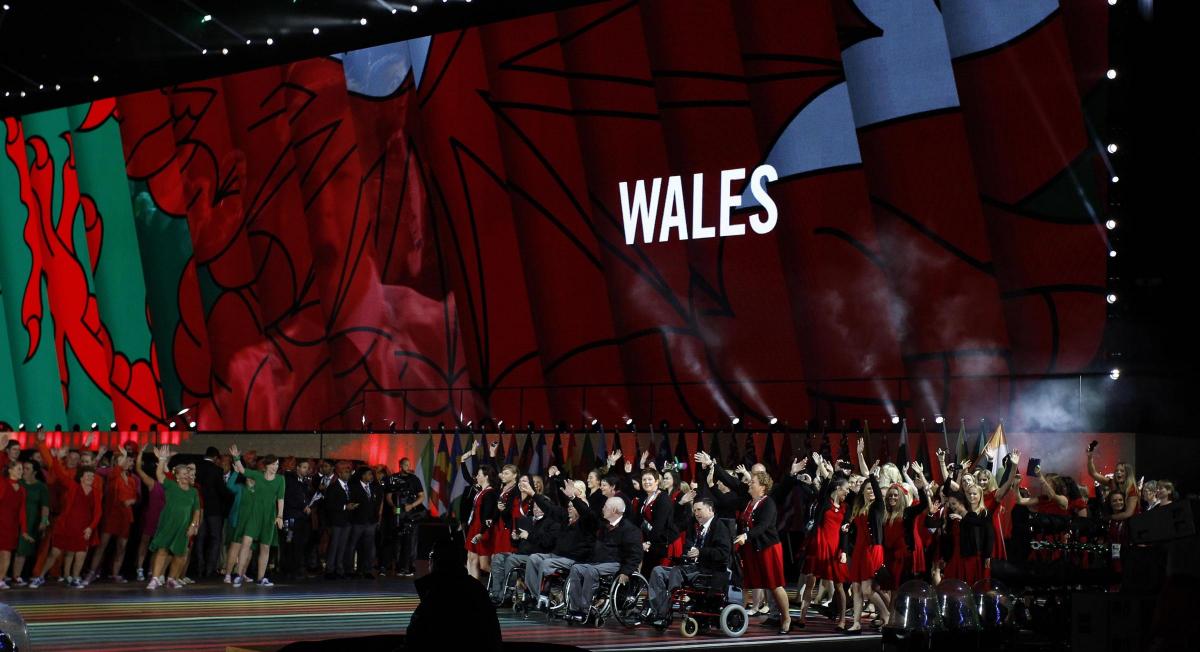

Wales has not staged the event since the black and white world of 1958 – so long ago that it was then known as the British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

And, following the success of Team Wales at Glasgow 2014, there appeared to be some momentum behind a potential bid for the 2026 edition.

But in July the Government announced that it had decided against bidding, blaming the uncertainty created by the Brexit vote and concerns about the cost and the lack of economic benefits highlighted in a feasibility study.

That study has now been published in full and it reads like a 129-page version of that moment on Bullseye when Jim Bowen would invite contestants to “come and have a look at what you could have won.”

But rather than a carriage clock or even a speedboat, Gwent would have benefited from state of the art sporting facilities and it would also have hosted the athletes’ village at the St. Modwen Glan Llyn development on the former Llanwern Steelworks site.

Defending the decision to drop out of the bidding process, economy and infrastructure secretary Ken Skates pointed to projected costs of between £1.32bn and £1.54bn.

He argued that such costs would involve a “huge additional financial commitment” from the Welsh Government over three Assembly terms.

And the feasibility report also concludes that the economic benefit to the country could end up being zero.

But Birmingham, which recently announced its intention to bid for the 2026 Games, is hoping for a £390m economic windfall and points to the £740m generated for the Scottish economy by the 2014 event, which also brought in 690,000 more visitors to the area.

Civic leaders said the event would be able to “showcase the very best” of the city and deliver a “huge economic impact” to the West Midlands.

The city highlighted the possible financial legacy – creating thousands of new jobs, benefiting local suppliers, and boosting existing transport and housing plans.

And David Grevemberg, chief executive of the Commonwealth Games Federation, said he was “surprised by the ambitious costs quoted and attributed to the Games” in the Welsh Government’s feasibility study.

He added that “the last edition of the Games in Glasgow in 2014 was operationally delivered for £543m – and indeed £32m under budget – according to an independent Audit Scotland report.”

There would have been competition from Birmingham, Liverpool and possibly Auckland, Edmonton and Papua New Guinea but a Welsh bid was being positively encouraged by the authorities.

Setting aside the arguments about money, there were so many other potential benefits – including raising the nation’s profile internationally and inspiring the next generation of sporting talent.

And, having been lucky enough to cover the 2014 Games in Glasgow, I can attest to the buzz and feel-good factor that the event can create in a city and the wider region.

It’s now clear what Wales as a whole, and Gwent in particular, has missed out on.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here