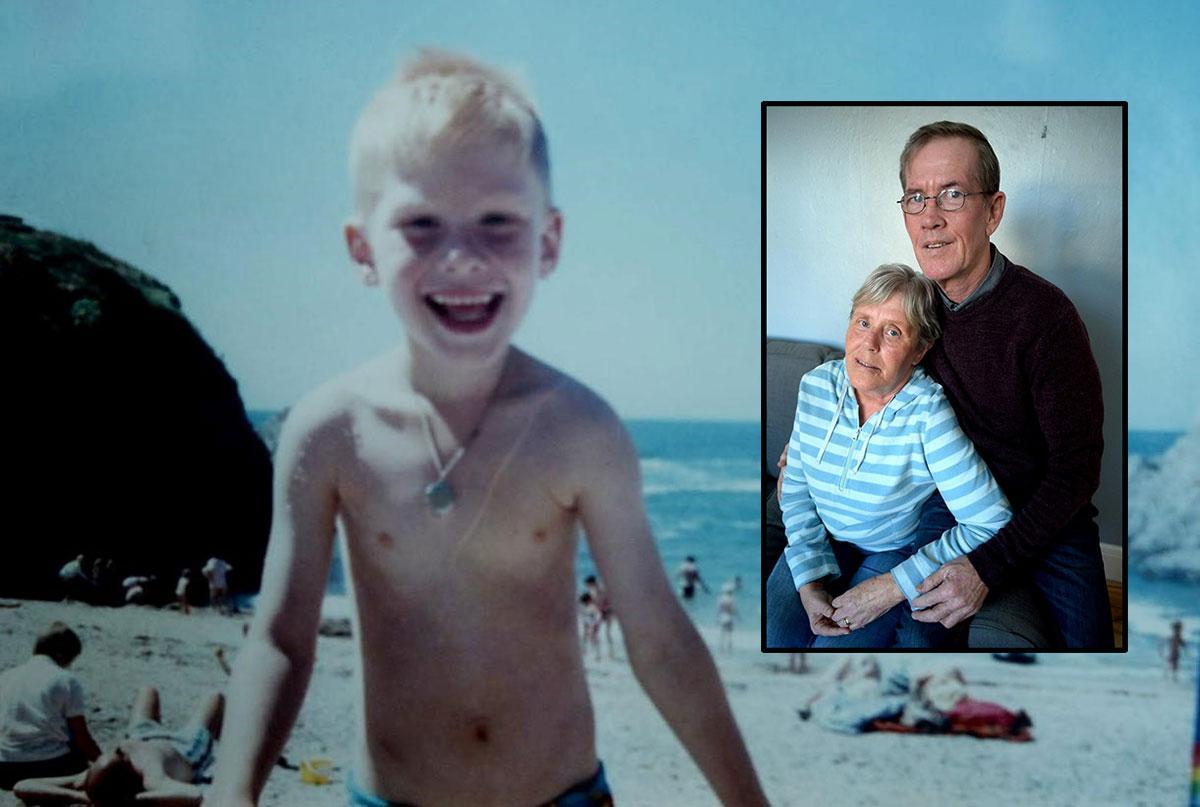

IT HAS been 25 years since Newport seven-year-old Colin Smith died of AIDS, contracted after he went to hospital with an ear infection and received contaminated blood.

But his parents have never stopped fighting for an official apology from the government – and mum Janet Smith, aged 59, says she wants justice so her son can rest in peace.

Colin was just one of at least 1,757 people with haemophilia, a genetic disease where blood doesn’t clot properly, who died after being treated with infected blood in the UK from the 1970s until the early 1990s.

He contracted HIV and hepatitis C after being given the clotting protein Factor VIII from an American prisoner.

Weighing just 13lb when he died, he was so light his parents had to pick him up in a sheepskin.

“There was just nothing left - it was heartbreaking,” said Mrs Smith.

Back in the 1980s, HIV was still a new and poorly understood infection, and the Smiths, from Aberthaw Road, Alway, said they became known locally as the ‘AIDS family’ after they found out about Colin’s condition when he was just a toddler.

Janet said: “All Colin ever knew was hospital treatments and drugs.”

Secrecy surrounding his condition continued even after his death, as the family only found out he had also been infected with Hepatitis C when they received cards in the post asking them to come in for a test three years later.

“We didn’t even know he had it. I asked the doctor, “what did Colin die of, AIDS or Hep C?” He just looked at me and said it could have been either,” said Mrs Smith.

January 13 marked the 25th anniversary of his death, and the family went to visit his grave, lay flowers and give him cards.

They try to include him in everything they do, putting a party hat on his picture for his dad’s fiftieth birthday and taking him Christmas presents.

Mrs Smith always receives a Mother’s Day card from her son too, written by her sister.

“He should never have died”, she said.

“He had a life to live and that’s what we miss more than anything. We could have had a couple more grandchildren now – we missed out, and he missed out on a life.”

In the three decades since the start of the nightmare, the family have not had an official apology.

The contaminated blood scandal was the fifteenth biggest peacetime disaster in British history.

His family believe the NHS should have taken steps to safeguard those patients.

“The government knew there was contaminated blood out there in the early 1970s but they still gave it to my little boy,” said Mrs Smith.

“He wasn’t born until 1982 and he should never, ever have been infected. All his life was hospitals, drugs and drips up the nose which he absolutely hated. He had no life.”

She said Colin’s three elder brothers are still affected by having to watch their sibling go through his ordeal.

Children themselves at the time, they didn’t understand what was happening and their mother explained by telling them Colin had “special blood.”

Once, Mrs Smith said, she phoned the local hospital, concerned that Colin was having a severe nose bleed.

“All they told us was to make sure we burned his mattress”, she said.

“They were so against us bringing him home to die, but we were determined.”

She added that she had to fight to have him buried rather than cremated, which was recommended because of his condition.

“We wanted a burial so we could go to visit him, which we still do every week,” she said.

The issue of contaminated blood was debated in parliament on Thursday, with MPs including Newport East’s representative Jessica Morden calling for a final resolution to the issue.

Mrs Smith is happy the issue may finally be moving forward, but added: “Every time there’s a debate our grieving starts all over again because nothing comes of it. We need a result soon, because people are dying. It’s not about the money, it’s about an apology.”

Newport East MP Jessica Morden backed calls for a resolution. She said: “While long overdue, it is time for a public apology and a final settlement. Anything less will just continue to hurt the innocent victims and their families who, through absolutely no fault of their own, have had their lives torn apart by this national scandal.”

During the debate, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Health Jane Ellison said ministers were still waiting for a report to be published from the Penrose Inquiry in Scotland.

But she told MPs events had already been examined in court and said the Department of Health had published all the relevant documents until 1986 on its website.

There was scope to review the financial support given to those affected, she said, but added: “Support currently provided is over and above any other state benefits that infected individuals and their families may receive.”

MPs voted in favour of a motion to look again at the response to contamination.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel