Read how a German bomber crashed on a Newport street killing two teenagers

NEWPORT was not the target that night. The German Heinkel bomber was returning from a mission to attack industrial targets near Liverpool.

But the destruction it wrought on Newport was every bit as severe.

The Phillips were a respected Newport family who ran a tobacconist shop in town.

Malcolm, 17, was a well-known sight around Newport as he carried his beloved spaniel around in a bicycle sidecar. His sister was 14-year-old Myrtle.

They lived in one of the large detached houses on Stow Park Avenue. On the night of 13th September 1940, the children happened to be sleeping downstairs. It was to be a choice that had the most profound consequences.

By September 1940, what became known as the Battle of Britain reached a new level of intensity as the Luftwaffe began bombing British cities at night.

German pilot Harry Wappler and his crew of three had taken off from their base in northern France at 10.30pm and headed for their target - Liverpool. With him was Navigator Fritz Berndt, Wireless Operator Johannes Elster and bomb-aimer Herbert Okuneck.

Having struck their target of Ellesmere Port, Berndt gave Wappler his course for home and the Heinkel headed south.

There were few effective defences against night bombing in Britain at this time. Night fighters equipped with radar had still not entered service. Anti-aircraft guns were not yet linked up with radar, making targeting in the dark very difficult.

One deterrent we had was the barrage balloon. These were unmanned airships filled with hydrogen and would float tethered by a steel cable at anything up to 7,000ft.

They were deployed around important targets so enemy aircraft would be unable to fly low and aim their bombs accurately for fear of hitting the cables securing the balloons to the ground. Some had explosive charges which would explode when they were struck by aircraft.

Newport, as a dock town and vital railway junction was protected by these balloons. Among them was 966 Sqn of the Royal Air Force, a barrage balloon unit formed only three weeks before and based at Tredegar House.

By 3.15am, the crew of the Heinkel must have believed they were almost home and dry. As they neared the South Wales coast, they would only have to cross the West Country before they would be over the Channel.

Their journey was about to change suddenly and violently. The bomber struck the cable belonging to Number 10 balloon which was tethered at 6500 feet. Flying at around 250mph the Heinkel the force of the collision was so great that the aircraft was spun round the cable which was wrenched from the storage drum on the ground, which in turn was fixed to a lorry. The vehicle was lifted off the ground by the force of impact.

The bomber was still flying, but losing height, and now was heading east as Wappler struggled to lift the machine and maintain his course.

Raymond Slocombe was a seven-year-old boy living on Maesglas Avenue and he can still remember the drama "like it was yesterday". He saw the bomber flying in low over the houses with the left engine on fire.

As he watched from his bedroom he saw the Heinkel "coming from the direction of the docks heading towards Belle Vue Park".

To the young boy it was cause for celebration. He cheered as the plane struggled to gain height and get over the hill. That struggle would end in catastrophe for another Newport family barely two miles away.

The luckless plane then hit another cable; another balloon standing silent guard, this time in Belle Vue Park. This signalled the end for the bomber.

The Air Raid Patrol (ARP) report for that night tells how at 0400: "An enemy plane has crashed on No.31 [sic] Stow Park Avenue. One parachutist baled out and picked up in Queens Street and taken to Royal Gwent Hospital. No particulars of any other occupants."

Wappler had managed to escape, but the other three crew were not so lucky. Trapped in their burning aircraft, they ploughed into Stow Park Avenue, just beyond Belle Vue Park.

The Phillips family would have had little warning as the Heinkel came hurtling towards their home.

The Argus reported residents nearby hearing a 'stifled roar' as the aircraft hit the house. Incendiary or fire bombs still carried by the aircraft are believed to have exploded on impact.

The Argus report, constrained by wartime censorship, could only describe the bomber crash 'on a Welsh coastal town'

Malcolm is reported to have rushed into his parents' room shouting "Dad the house is on fire!" The report continues:" Malcolm ran back to the rear wing of the house in an attempt to rescue his sister and the spaniel who were trapped on the ground floor of the blazing building. That was the last his parents saw of him, although his father closely followed him.

“Fierce flames and clouds of acrid smoke were by then sweeping the back of the premises and the father was driven back."

Meanwhile, Mrs Phillips had tied bed sheets together and using these as a rope, she and her husband climbed the 20 feet down to safety.

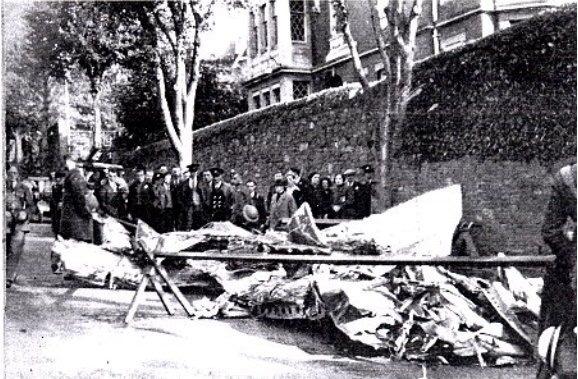

As morning came, the Argus report told us, flames still flickered as firemen damped down the blaze. A wing of the bomber lay strewn across the lawn.

Harry Poloway is famous as Newport's toastmaster and someone who has witnessed many great events the city has seen. That night he saw one of its grimmest episodes. A friend of the Phillips family, he was Master of Ceremonies at a packed dance laid on for forces personnel at St Johns in Newport.

"I was very friendly with the family" he recalls. I would teach Malcolm and Myrtle to dance - they used to call me 'Uncle Harry'.

Harry was Newport's senior electrical engineer and he was called from the dance after reports came in of an aircraft crashing into a house in Newport and he was needed to assess damage to power supplies.

A car was sent to take him there, but he only realised which house it was as they pulled up outside.

Harry remembers it was still burning and the fire crew's concern that it would guide more bombers to them. By this time they knew the children had died.

"I felt so sad, broken-hearted" the 100-year-old recalls. "But I still had a job to do. I had to check the electrical supply to the area was safe." As he worked a wall collapsed, injuring his leg.

He remembers this incident as the one which made him determined to 'do his bit' and join the armed forces. As a senior electrical engineer, he was in a 'reserved occupation' and was excused military service. "But now I volunteered to fight" he says "and Newport Corporation agreed to let me go".

In the days that followed, the Argus, constrained by wartime censorship, could not report that the bomber had come down in Newport, but instead had to refer to it as a 'Welsh coastal town'.

Pictures later appeared showing the wreckage on Stow Park Avenue, but carefully cropped so as to not give away the exact location.

The surviving parents on the afternoon of the day their two children died, went to visit the pilot of the German bomber Wappler in the Royal Gwent.

Pieces of the aircraft were made into rings which were sold to raise money for the war effort.

Newport wartime artist Stanley Lewis incorporated the tragedy into his painting 'The Home Front' - a moving collage depicting the trials of civilian life in wartime.

'The Home Front' by Newport artist Stanley Lewis. The Heinkel bomber is depicted top-left.

Wappler, would spend the rest of the war in captivity, despite a brazen attempt to escape by stealing an RAF aircraft. After the war he returned twice to Newport, the place where he had almost met his end and others had perished that night.

The site of the Phillips' house on 32 Stow Park Avenue is today noticeably different to its neighbours. The line of handsome detached Victorian villas is broken where the bomber obliterated the house. Today a smaller, modern building sits tight against its larger neighbour, like brick and mortar scar tissue. It is shielded from view by a large conifer.

32 Stow Park Avenue today

A Newport man who has done much research on the tragedy, Shaun McGuire, believes there should instead be a visible public memorial to Malcolm and Myrtle Phillips.

Shaun says Malcolm displayed "extreme heroism" after making sure his parents were safe and well and then immediately going back into the flames to rescue his sister. "How many 17-year-olds would do that? His first thoughts were for his parents and his sister. I think this heroism in a boy so young deserves to be recognised."

They are buried together in Newport's Jewish cemetery and remembered with a striking gravestone in English and Hebrew. Perhaps one day a memorial set on the wall outside the house where Malcolm and Myrtle played will tell of the extraordinary sorrow and heroism that was played out that day.

Acknowledgements: Shaun McGuire, Peter Garwood

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here