THE coverage the Argus gave of the first Gulf War was not just of the fighting in the air and on the ground.

We told of the many local links with the conflict – Gwent people held hostage in Iraq, Kuwaiti refugees living here, campaigners for peace, Gwent firms which produced weapons used in the conflict and, of course, local people called upon to fight.

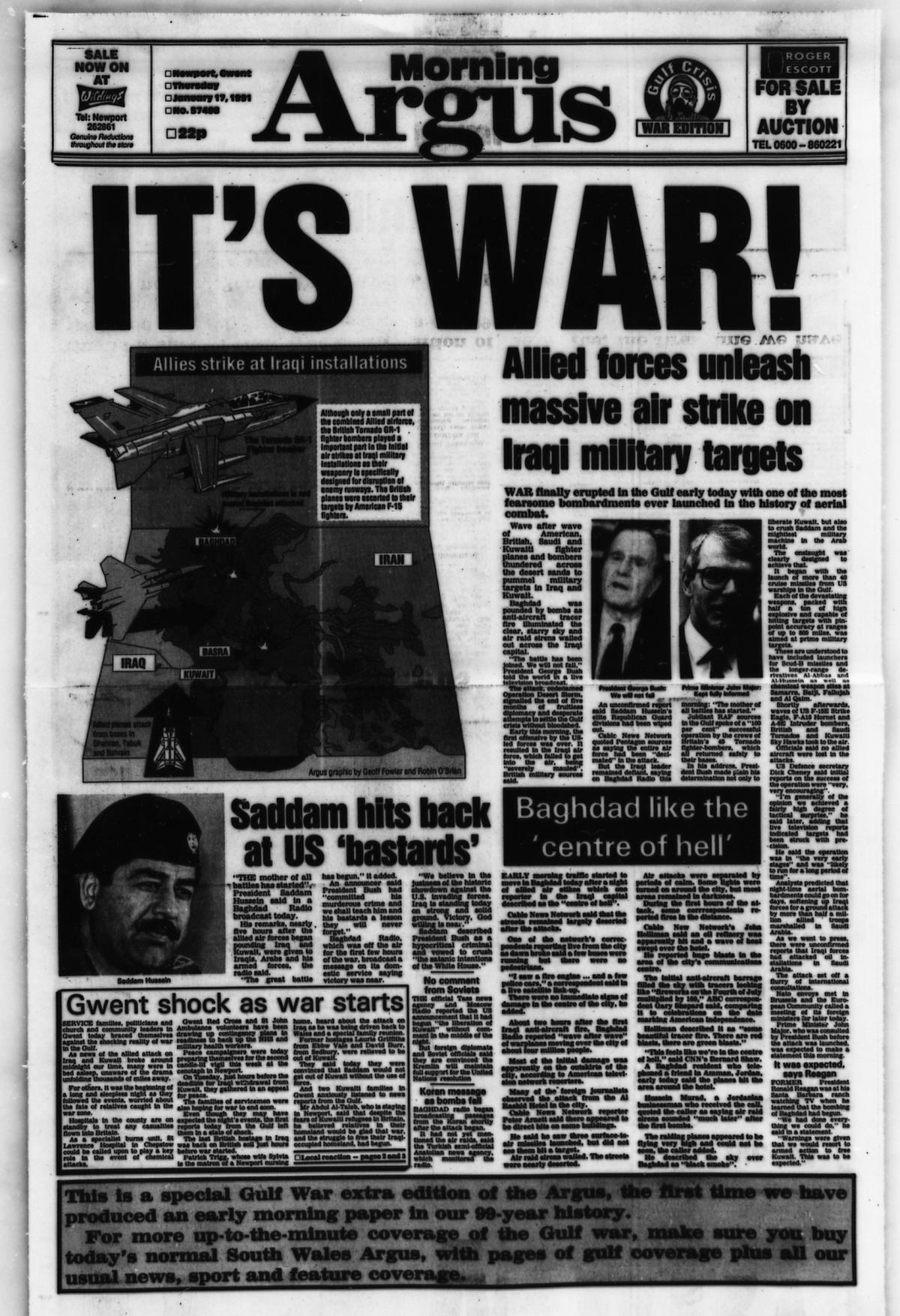

On the day war broke out, the Argus printed what we called a 'Special Gulf War' extra edition.

This, the strapline said was "the first time we have produced an early morning paper in our 99-year history".

Reporters monitored the situation 24-hours-a-day – ready with updates for the morning's first edition.

The front page of the Argus that day said simply 'It's War!'

It told also of the shock across the county as the airstrikes began.

Peace campaigners were preparing for a second candle-lit vigil at the cenotaph in Newport.

They had gathered there days earlier, hours before the deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait passed.

One of the organisers of the demonstration, Newport councillor Cyril Summers, said he was shocked by the news the airstrikes had started.

"This is absolutely dreadful," he said.

"We were still hopeful that even after the deadline, negotiations or a last diplomatic effort would still have occurred and that Britain and the US might have allowed sanctions to work longer."

Veteran peace campaigner, MEP and later Blaenau Gwent MP, Llew Smith said Saddam Hussein should have been defeated by economic sanctions.

He said: "The alternative will be gruesome."

Days before the airstrikes began, the last of the British hostages held by Saddam Hussein in Iraq and occupied Kuwait came home.

After the alliance of Western and Arab countries said they would use force to eject Iraq from Kuwait, Saddam Hussein ordered that Westerners working in Kuwait and Iraq be arrested.

Many were taken to key locations such as power stations and used as so-called 'human shields'.

Patrick Trigg, the husband of Sylvia Trigg, a matron at a Newport nursing home, was working as an engineer when he was arrested in September 1990, shortly after the invasion of Kuwait the previous month.

He endured four months in solitary confinement before being freed just before the allied airstrikes began.

David Burr from Chepstow was confined in his Kuwait apartment after the Iraqi invasion.

He admitted he was frightened: "We knew we were expendable. Hurd and Waldegrave [British government minsters] had made it clear that we might have to be sacrificed."

He noted that the Iraqi soldiers were young and demoralised: "They are like kids and they have no experience of war."

Former hostage Laurie Griffiths of Ebbw Vale had gone into hiding with David and they had escaped from Kuwait together.

He felt there was no other option but to use force to eject Saddam from Kuwait.

"When we see a bully getting his come-uppance, we all get a sense of satisfaction," he said.

"I hope that when he gets a good bashing and when he sees that blood has been shed, he will surrender."

Ex-Monmouth school pupil Keith Forshaw called the Argus from the Gulf to tell how he escaped over the border from Kuwait into Saudi Arabia, but saw one of his fellow escapees shot dead.

Many weapons used in the war were made in Gwent.

The Royal Ordnance Factory at Glascoed produced the specialised weapon used by the RAF to destroy runways.

The Hunting Engineering JP233 airfield attack system would see small bombs and mines deployed to stop aircraft taking off and prevent repair work taking place.

Low-flying Tornado fighter-bombers dropping these were among the RAF aircraft shot down during the war.

Three Gwent firms produced equipment and chemicals to combat the poison gases stocked by Iraq.

Tredegar firm Penn Pharmaceuticals produced huge quantities of antidotes to arsenic, mustard, cyanide and nerve gas.

Gas masks made by Cwmbran-based firm Siebe Gorman were increasingly in demand.

As fears grew that Saddam would unleash chemical weapons on allied forces, the firm began supplying gas masks to Saudi Arabia with interest coming from other Arab countries.

Newport firm J Compton Sons and Webb was also part of the allies’ chemical warfare defences.

It produced the rubber Nuclear Biological Chemical (NBC) suits which protected troops from potential attack.

A Gwent firm was involved in an arms scandal which broke before the war.

The so-called Iraq supergun was a project which employed engineers from a Cwmbran recruitment firm Kelter Consultants said they unwittingly placed the 20 workers on the multi-million pound project to build a gun with a 50-foot barrel which could bombard neighbouring countries.

Under the headline 'Volunteers stand by', the Argus told of the British Red Cross and St John volunteers who were standing by to help treat any casualties from the Gulf.

The services had set up a headquarters in Newport to co-ordinate their response.

The Royal Gwent Hospital in Newport and the burns unit of St Lawrence Hospital in Chepstow were on standby to receive military casualties.

Kuwaiti refugees living in Gwent watched anxiously as the war began.

The Argus told of the Al-Taleb family, who by chance were staying on Chepstow Road in Newport on a home-exchange holiday when the Iraqis invaded.

Father Abdul Al-Taleb said he didn't think the war would be a long one, but warned: "It will be a bloody because Saddam will use chemical weapons and I think he will direct them at Kuwait."

Gwent-based Kuwaiti businessman Ashraf Barakat also stayed up all night watching footage of the air strikes.

He said he would not rest until he knew that Kuwait was safe and allied troops were safe, adding: "There are many Welsh boys from the Valleys fighting on our behalf.

"We would like to see them back with their families."

There were many of those boys from the Valleys and elsewhere in Gwent ready to fight as their families waited anxiously for news.

Ex-Hartridge School pupil Flight Lieutenant Phil Luxton was due to return to the Gulf on January 15, the day the UN resolution calling for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait was to expire.

He was part of the team maintaining Tornado F3 fighters at Dharan airbase in Saudi Arabia.

At the family home on Gibbs Road in Newport, the 28-year-old's father Tony said: "I have some misgivings about the war but you have to do what you have to do."

The Queen's Dragoon Guards, or the Welsh Cavalry had mobilised from their base in what was then West Germany to the border with Kuwait, ready to move with the invasion.

Major Hamish MacDonald said: "I'm bloody proud of this squadron and Wales should be bloody proud too."

The Durston family of Glasllwch Crescent in Newport had two sons, Stephen and David on the frontline with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers with the 7th Armoured Division.

They had another son, Peter, who was in the RAF and had just returned from the Gulf.

He was expecting to go back at any time.

"We are just going to have to sit tight and hope for the best," said dad Ralph.

Another airman, Marc Thomas, 24, of Greenmeadow, Cwmbran was giving his family something to laugh about as he served with 43 Squadron servicing Tornadoes in Saudi Arabia.

He told in a letter home how he wrote a poem which he performed at the unit's Christmas show.

Called Christmas in the Sand, it included the lines: "So on this alternative Christmas; Some things must be said; A message I've sent home with all my love; And prayers I've said to see the White Dove; But one message I've kept under wraps; And that's to you Saddam, you're an *********!"

Marc added: "Excuse my French but it was needed to express my feelings about the situation.”

The Argus sounded a less warlike note in its leader.

Saying that although we should not give in to Saddam's aggression, it said: “The question of a Palestinian homeland should be put on the same agenda and that once he had been removed from Kuwait a Middle East summit must be helped to settle all these issues.”

The column ended grimly: "We have no stomach for this fight and when the bodies of soldiers come back in bags, it will be too late to say that the West might have tried harder to find some grounds for a middle road with this most aggressive and difficult of men.

"We are now resigned to the fact that it is no longer a question of 'if', merely a question of 'when'. But we cannot pretend that we like it even the tiniest bit."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel