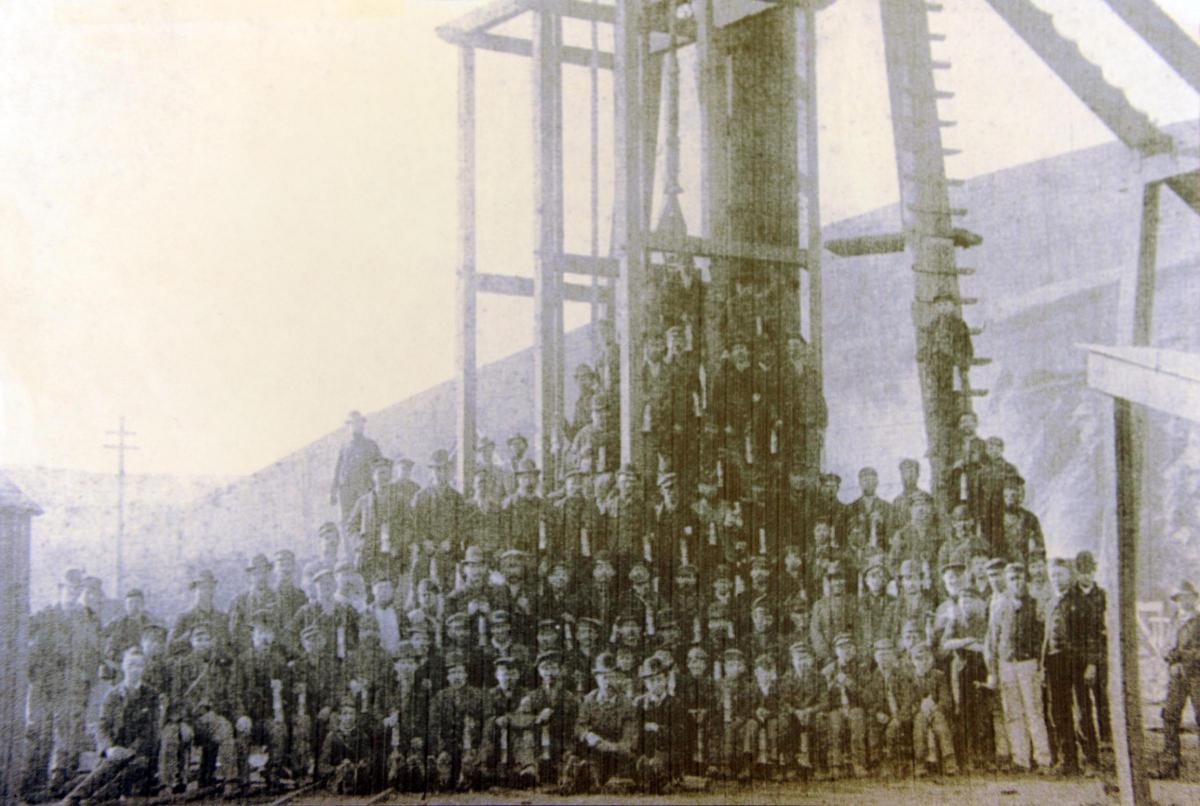

ON Thursday, February 6, 1890, around three hundred men left their homes in the tight terraced streets of Abersychan, Cwmffrwdoer, Talywain and more to begin another day toiling underground at Llanerch Colliery.

Fewer than half of them would return.

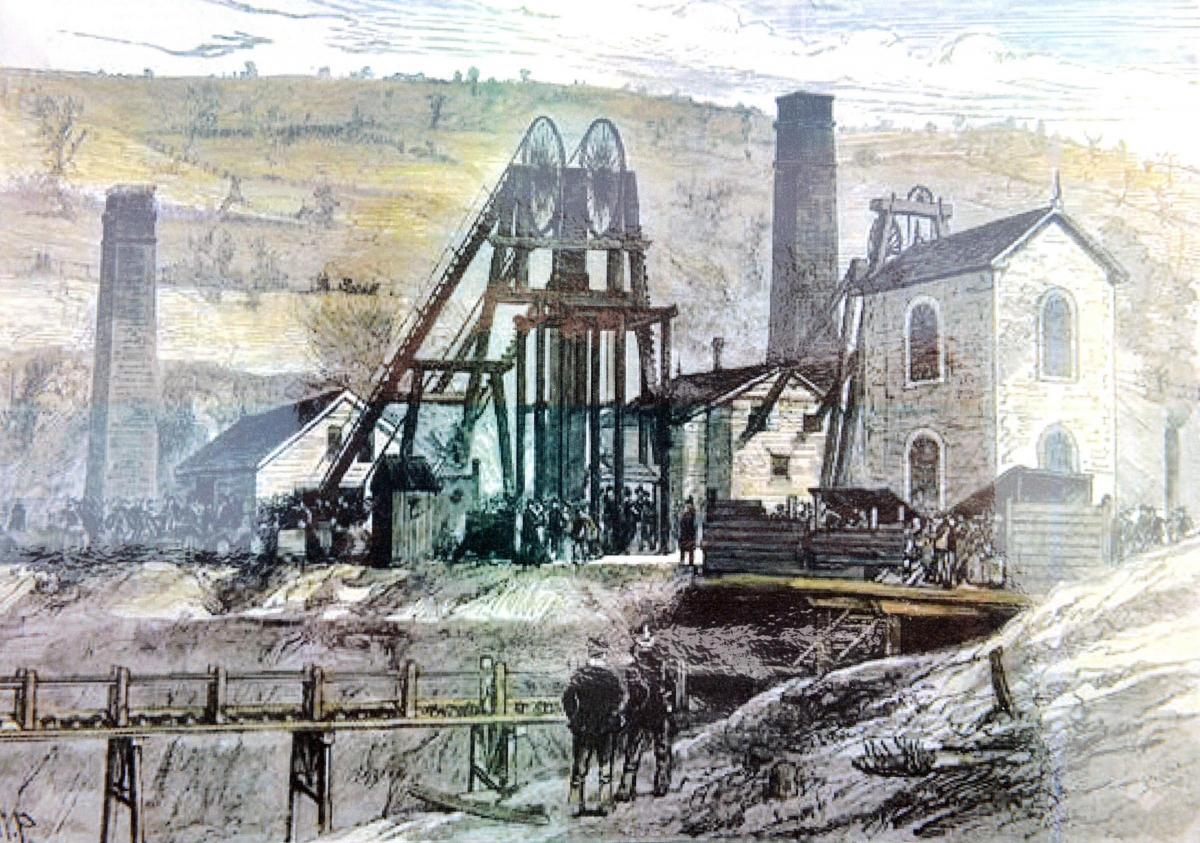

Just before 9am an explosion, so violent it was heard for miles around, blasted through the workings deep underground. Bodies of men and horses were broken and crushed.

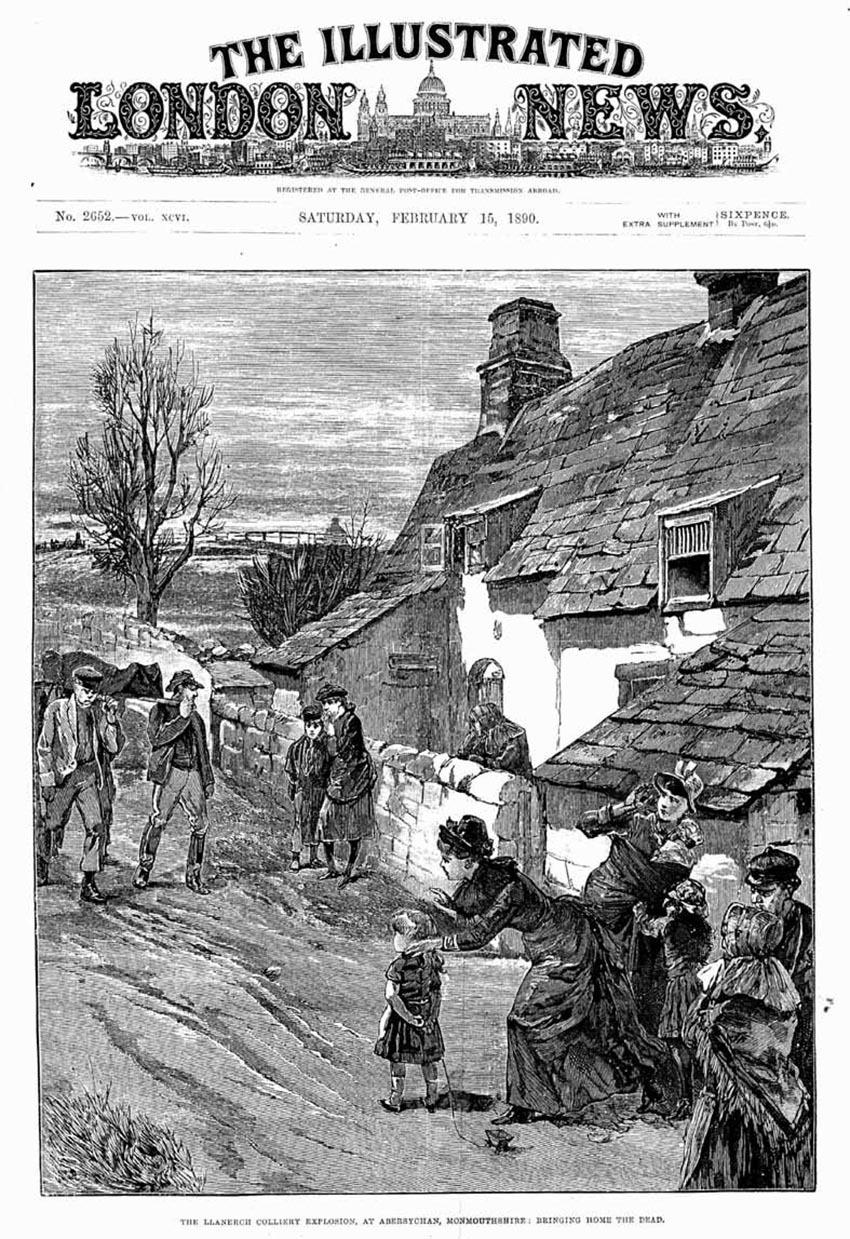

The sombre days and weeks which followed were filled with funerals, memorials and the inquest into the disaster which struck this mining community. Our sister paper the Pontypool Free Press reported on the tragedy and the aftermath.

One WB Witchell told how he was close by and rushed to the colliery. “As soon as I heard of the catastrophe I went at once to the scene of the explosion. Such a scene I never saw before, and hope never to see again. Such a terrible stroke which has been duly brought before our notice by you, and the tremendous sorrow and affliction brought to scores of homes no words can possibly express.”

Joseph Morgan, the manager of the colliery led a team of rescuers. He told how he went to the colliery on the morning of the explosion with men from Abersychan to the colliery at around 6am. He went to descend with a group of miners, but was called back. He had talked to another group led by one Henry Hillier; these men were to die.

After the blast, he entered the subterranean carnage below. They first found unconscious men. One was Tom Langley. The rescue party dragged him back to the shaft. Another called Jenkins was taken to the pit bottom.

The sights became more gruesome: “I found John Beard had been dragged from the bottom of the pit and put to sit in a little airway, his foot was cut off and he was bleeding very freely. I tied a scarf round his leg, putting pressure upon the artery to stop the flow of blood.”

He told how they saw “affecting mementoes of the dead”. On timbers, ripped clothing was left, he supposed by “poor fellows who fled for dear life”.

They walked down Cook’s Slope and to get to the bodies. “It was here that the destruction was most severe” he recalled. As they walked forward flames still licked around them.

The coal seam Meadow Vein was worked by naked lights, or open flames, which was common in many pits then.

The inquest into the disaster later heard that there was a strong feeling against the use of ‘locked’ or safety lamps. Several nearby collieries, Cwmbran, Tranch, Pontnewynydd, British Top Pits, were all worked by ‘naked lights’. Could these have caused the explosion?

It was later revealed many of the workers at Llanerch said they did not want safety-lamps there. It was said the men did not think the use of the locked lamp necessary, and had “pooh-poohed” the idea.

Tributes were later paid to those rescuers. The Abersychan Local Board (local council) thanked those who had risked their own lives to rescue others – “those brave men who, at the risk of their lives, so promptly descended the Llanerch Pit, almost immediately after the explosion, and continued to do so till all the bodies were recovered”.

The impact of this catastrophe on a place the size of Abersychan would have been enormous. They added sadly: “Our streets have been emptied of the flower and the youth of our male population, the average age of those lost by the accident being under 27 years.”

A month after the disaster, an inquest sat at Pontypool Town Hall. The jury had to decide on causes of death of Joseph Howells, Henry Howells, William Tugday, and the 171 others ‘either killed on the spot or who died subsequently’.

They found they had died “in consequence of an explosion of inflammable gas in Cook’s Slope, Meadow Vein seam, Llanerch Colliery.”

They found also the explosion originally happened at a part of the seam called Number four heading from an “outburst or accumulation of gas”; and that the original explosion probably caused other gas to escape, causing more explosions throughout the working.

The jurors did not blame those who ran the mine, finding that the owners, staff and men believed the mine was safe for working with naked lights, and that “such belief was then reasonable”.

They added there was “certainly not sufficient proof” to attach culpable liability to anyone for the disaster, nor sufficient general probability of the explosion occurring from naked lights to hold anyone primarily responsible for their habitual use before the blast.

Among the many services held to remember the victims of the disaster, was one at the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Abersychan which had lost many of its congregation. William Allsopp had been conductor of the choir for over 30 years. His loss would be “keenly felt by the church and choir”. James Lewis, the accompanist of the choir and Sunday School teacher also died.

Others from the chapel were lost. Benjamin Meadows, who had been a class leader for many years. John Jones, another Sunday School teacher, and his son, William John, were both members of the chapel choir, and several members of the Sunday School, all “bright, intelligent young men”. The report added sadly: “this place of worship has suffered the most according to its size.”

Towns and villages across Wales lived with the knowledge that these disasters could strike any one of them at any time. And when that disaster befell one, others rallied. Miners at South Wales Colliery in Cwmtillery decided to contribute one shilling from each adult and six pence from each boy to aid relief of the dead men’s families.

Concerts were held to raise funds, The Abertillery Histrionic Society and Temperance Brass Band “intended holding entertainments” in aid of the fund, while an organ recital was to be held in Abersychan. The Blaenavon Gas and Water Company paid ten guineas to the fund. Word of the fund had spread far and wide. We learned that “a gentleman and a lady from Bristol” had each forwarded a guinea apiece towards the fund.

One of those who perished was the kind those towns could ill-afford to lose. A leader at work, at home and in his community.

Edward Jones, 60, we were told, was known and respected “over a large area”. We were told too that “as a Christian man he was one of the brightest and best. At home in the family he let his light shine, hence he leaves behind him a family to call him blessed. Amongst his fellow-workmen he was a power for good. The tribute told how “few men would swear when he was near”.

But he would not be forgotten. A stained glass window at St Cadoc’s in Trevethin still recalls the catastrophe. And many years later, people gather, as they did this week , to remember a time when work was so dangerous that it had the power to shatter whole communities.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel