ONE of the Gwent prisoners of war captured at Dunkirk kept a diary of his time behind the wire during the Second World War. MARTIN WADE tells of the grim captivity of Sapper Samuel Grace.

The hell of Dunkirk was very real for the thousands of soldiers who escaped the encircling Nazi hordes.

Sheltering amid the sand dunes, they waited their turn to be taken home as dive bombers dropped bombs and machine-gunned them.

But those who didn't make it back to Blighty faced this and another torment.

Samuel Grace was one of these. In those desperate days of May and early June 1940, he would suffer trauma that he would carry with him until he returned to Hoskin Street in Newport and until the day he died says his daughter, Dawn Hillier.

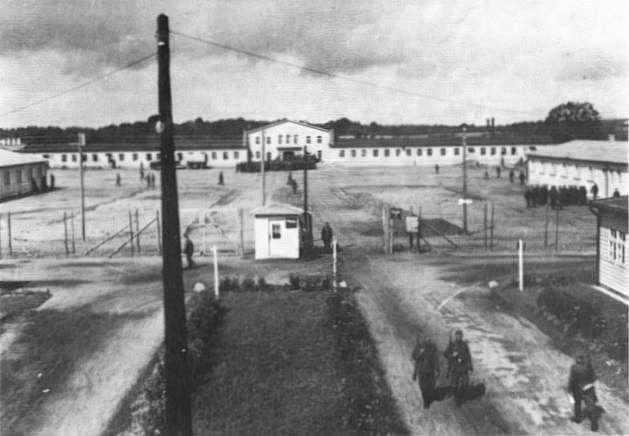

He kept a diary between 1942 and 1945 of his captivity in Stalag XXA.

Sam joined the Royal Engineers in April 1939 and was called up soon before war broke out on September 1 that year. Two weeks later he was sent to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force, formed to help protect the country from German attack.

As the allies fell back across northern France in late May 1940, Sam was given the task of blowing up a bridge.

Dawn tells how his war ended: “They set the explosives and were waiting for the order from a French unit to blow the bridge. The order never came, but as they waited and waited, they were ambushed by a German patrol and taken prisoner”. So began five long years in captivity. "He never forgave the French after that" Dawn recalls.

The camp lay near Malbork (then Marienburg in Germany). The castle there formed the centre of a complex of prison camps.

Food and the lack of it dominated his thoughts. "Feeling effects of poor food" he often wrote. Often, they would be fed potatoes, some sausage and rye bread of varying quality and quantity. But sometimes, this meagre fare would have been seen as the height of luxury. Once he writes after finishing work on a day with snow and a "very cold wind blowing", he admits "conditions at Stalag are very bad - frying spud peelings."

There are occasions when their diet takes a turn for the better. A day of "beautiful weather" saw them felling trees and on their return, the cookhouse presented Sam's hut with a pie. They would have wolfed this rare treat down with dire consequences. Sam noted: "Affected lots of the men. They were running to the latrine all night."

Days would start early. The men would parade at 7.30am and then often would have to march for an hour and a half just to get to their workplace. Typically, they would finish at 4.30pm, although often worked until late into the evening. He writes one Spring Wednesday: "Working from seven til seven. Working on my knees. Very hungry during day."

As well as being gruelling and monotonous, there was also risk. He tells of one lucky escape: "Finished work at 12. I bought another loaf [from a Pole] for 20 fags. We were searched but I got away with it."

Sam took a great risk too in keeping his diary. If it had been discovered he could have been shot.

The letters from home gave diversion from their grey world of endless toil and hunger. They reminded the men that the world they left still existed. Mail - its arrival, rumours of its arrival and quantity were almost as important as what was in the letters themselves.

One entry showed the light that mail from home could cast on the darkest of days in the camp. "Day of days, as I received 18 letters from home, of which 15 were from my darling, Agnes, bless her. I am a lucky man."

With these letters, some sense of what was happening in the wider world and the war seeps through. Sam's friend Andy receives a letter in August 1943 "from his chum in Africa". By this time, the Germans had been defeated there and were in retreat in Italy and Russia. Soon after they learnt of Italy's surrender.

They found out too of the D-Day landings in France from a guard. "It is here at last" Sam writes, adding: "I wonder if it will finish this year?"

The diary changed briefly with talk of the allied advance dominating his thoughts, but the routine soon settled again into one of hard work in the fields and meagre food. The end of 1944 brought heavy rain and freezing temperatures leaving Sam with a fever and pounding headaches. He still had to work.

But they know that the war continues to go badly for the Germans as the Russians advance. This would have dire consequences for the PoWs.

In January 1945 Sam writes "Jerries in a flat spin. Joe [Joseph Stalin, Russian leader] taking town after town." On January 22, they were roused much earlier than usual. "Out of bed at 1am. Started marching in full kit”.

And so the prisoners from Sam's camp and the others across Poland were marched thousands of kilometres across northern Europe to escape the advancing Russians.

In temperatures as low as -20C, Sam often merely writes how long they have marched. "22nd Jan 30kms, 23rd Jan 20kms".

When they had walked for the day, they had to scrounge for food and sleep in barns. By early March he wrote how his toes "had turned septic."

By the 21st they had crossed the Elbe and marched into western Germany. The war was within days of its end, which of course Sam would not know. The 24th was "a black day". They were marching until 11pm and were given a loaf of bread between 15. "As the Russians advance, we keep marching for the allied lines."

Just two days later it would all end.

"Great day" Sam writes. "At 1pm American officers entered the village" he says, before adding: "We were liberated after five years of captivity."

The following days saw the men presented with tables groaning with food. "We had stew, packets of biscuits - loads of buckshee [free] grub about" Sam writes.

Many are ill as their bodies could not cope having been denied for so long. Sam has excruciating pains in his kidneys.

He was flown home the day after VE Day and after a spell in hospital in Hereford, he returned to Newport.

He married his beloved Agnes who had written to him so often the following month.

Dawn and her sister Jackie Whitehead visited Malbork in 2015. “We were in awe of being there” Dawn says “it was very emotional to make that connection. Growing up we’d only get glimpses of how it affected him.

“We wanted to go to find out more because he rarely mentioned it, but sometimes it came up almost accidentally.

“When I was a teenager I bought some clogs when they were fashionable in the 1960s. He was horrified as he had to wear them in the prison camp because their boots fell apart. His feet were gnarled and quite deformed because of that and the forced marches.”

That same methodical urge that made Sam risk his life to write down his experiences, saw Dawn meticulously copy every word of his tiny, pencil-written diary so that others could read it. “I feel it’s very important that his story is told” she says.

Like many returning from the war, he was reluctant to talk about his experiences, Dawn says. “We only found his diary sometime after he died”.

She is sure the toll taken on his health by his time as a PoW was not purely physical. “He was traumatised by the experience - his nerves were always bad after that”. She recalls bank holiday trips were sometimes mysteriously cancelled when her mother would announce that “dad had had a turn and was in bed.”

The ceaseless hard work and poor diet, combined often with no sense of when this torment would end must have worn many men down, both physically and mentally.

Sam died in 1973, aged only 53 and Dawn is sure his time at Stalag XXA hastened his end.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here