This week, Fred Hando again takes us on one of his ‘Rambles in Gwent’ as he goes to Llandogo.

TO Odoceus, Bishop of Llandaff in the sixth century, we owe the strange name of one of the exquisite Wye Valley hamlets —’Llandogo’.

The saintly Bishop had his dwelling and served his God on the banks of the mountain stream which cascades in fantastic leaps from the moorland down the steep hillside to the village.

Einion, King of Glewyssig, and his huntsmen had followed a stag for many hours through the wild woods. The hounds were about to leap on the stag when the weary beast dragged its body on to the cloak of Odoceus and collapsed, whereupon nothing would induce the hounds to attack it.

When the King discovered that the cloak belonged to the Bishop he prayed for pardon, bestowed the stag on Odoceus, and presented to Llandaff the whole of the ground over which he had hunted that day, from the Red Pool to the Wye.

We recognise the Red Pool as the virtuous Well of Trellech, but we know not where the Bishop dwelt, and the ancient church of Llandogo was demolished and rebuilt in the bleak middle years of the last century.

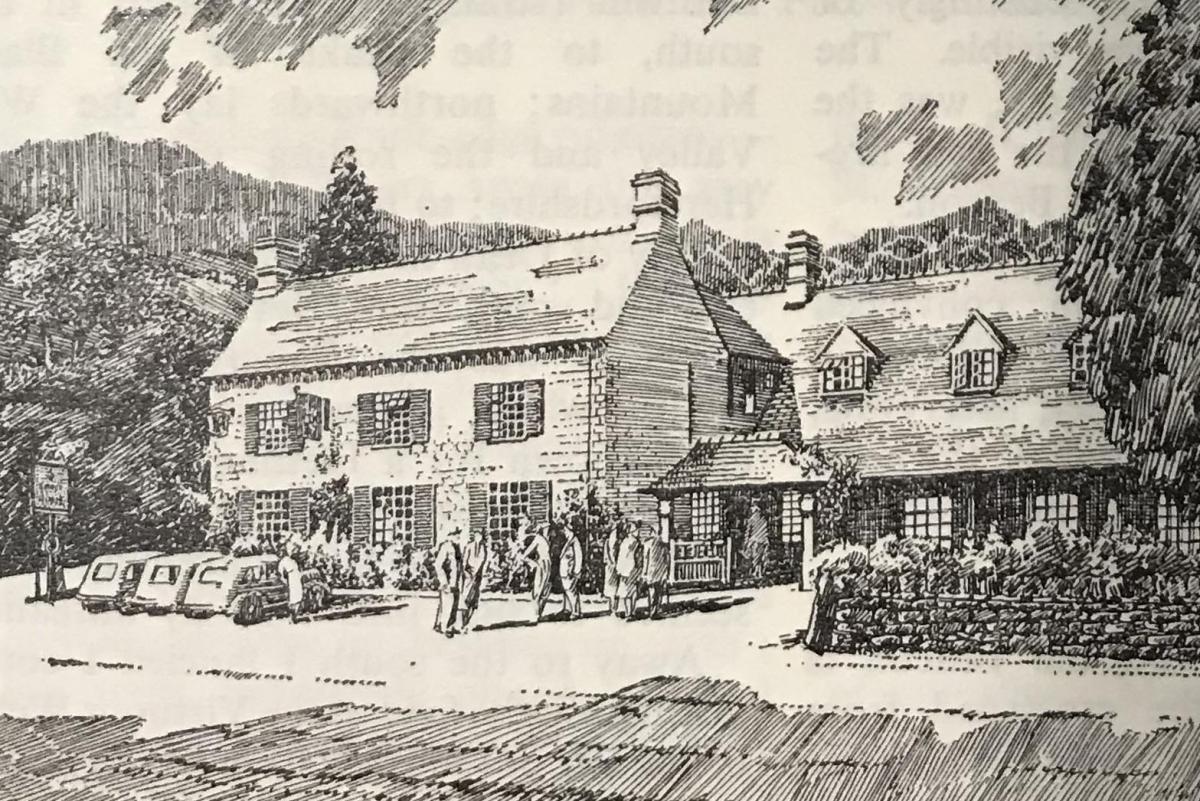

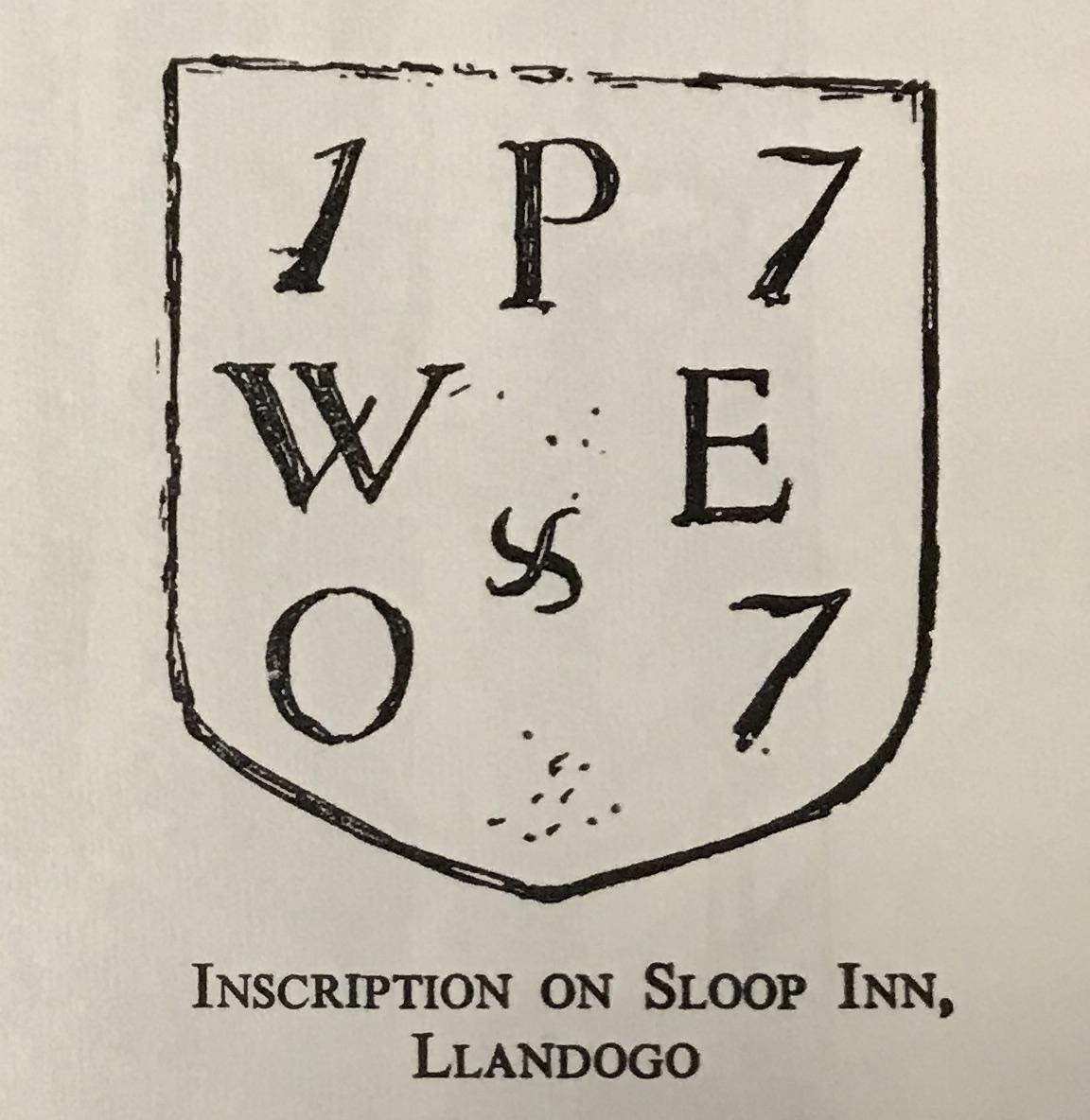

On a sunny November afternoon we halted at The Sloop Inn at Llandogo, I and walked around the old house. The original entrance and frontage were towards the river, and on this wall we found the inscription ‘P W E 1707’.

This reminded us that the patrons of The Sloop must have arrived by water, as no roads were laid down in the valley until the early years of the nineteenth century.

The name of the inn recalled the busy days when, at the head of the tide, Llandogo was the terminus of a busy trade route to Bristol.

So famous were the Llandogo trows (or sloops) that one of Bristol’s grand old inns, the Llandoger Trow (where Long John Silver served before setting out for ‘Treasure Island’) was named after such a craft, and a trow appears on the seal of the Borough of Monmouth.

Barges from Monmouth, Ross, and even Hereford, brought their goods to the wharves at Llandogo and Brockweir, and many a tale is still told of the feuds between the barge-owners on the one hand, and the salmon fishers and millers on the other, who found that the construction of weirs was a quick road to fortune.

The Sloop inn, we noticed with surprise, was built over the swiftly-flowing brook. “Can this water have come down from the waterfall?” asked Robert.

And when I assured him, he commanded with seven-year-old impudence, that we should discover the waterfall. We took the good winding road up the hill —two miles long — in short stages.

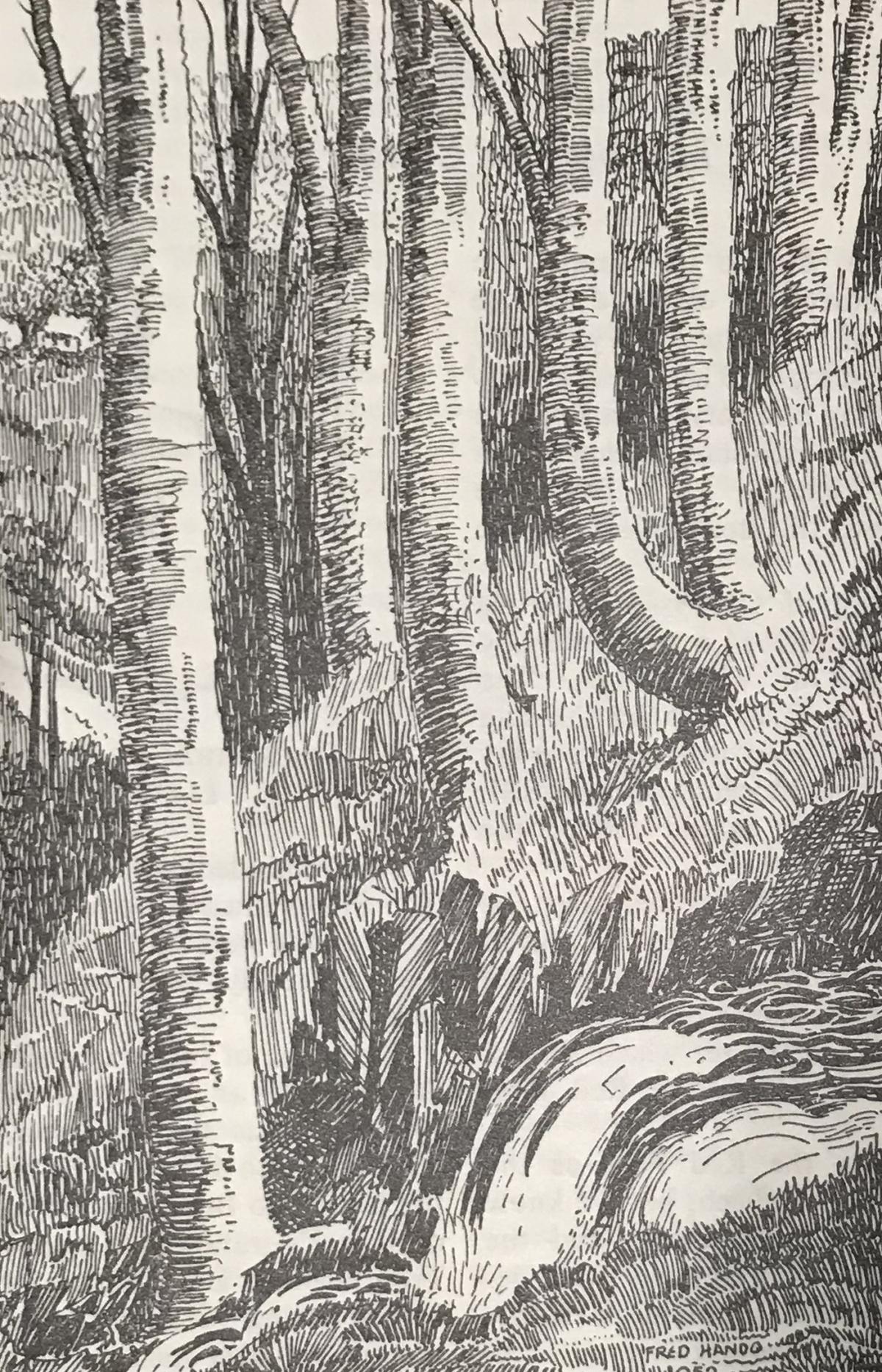

Ever and anon, through and over the honey-hued larch forest, we stopped to take the views. They were incredibly beautiful in the November sunshine —those trees, rocks, cottages and the blue river.

But where was the waterfall? Suddenly and shrilly, Robert (who has not read “Westerns” for nought) shouted; “I can see it shooting out of that gulch!” And against the skyline were Cleddon Shoots, cascades of molten silver against the shadowed cliff.

On again, up again, until we reached the heath, where the rich russet was relieved by the plantations of conifer. Along one of these plantations some genius had set an edging of crimson-berried bushes.

We turned right, and then right again, past Cleddon Hall, where Bertrand Russell was born, and soon afterwards we pulled up sharp to save ourselves from descending a forest path into Llandogo.

There, on the right, was the first cascade, and we were able to imagine this water leaping and leaping down the brown hillside, darting under The Sloop, and silvering the tawny flood-water of the Wye. Then we collected Robert, who, with his comrade Paul, was endeavouring to dam Cleddon Shoots at their peak with a huge boulder.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here