The Merthyr, Tredegar & Abergavenny Railway was a remarkable engineering achievement. Not only was it one of the most spectacular lines in Britain, but it was also one of the most difficult to build, and its long and steep gradients made it one of the most expensive to operate.

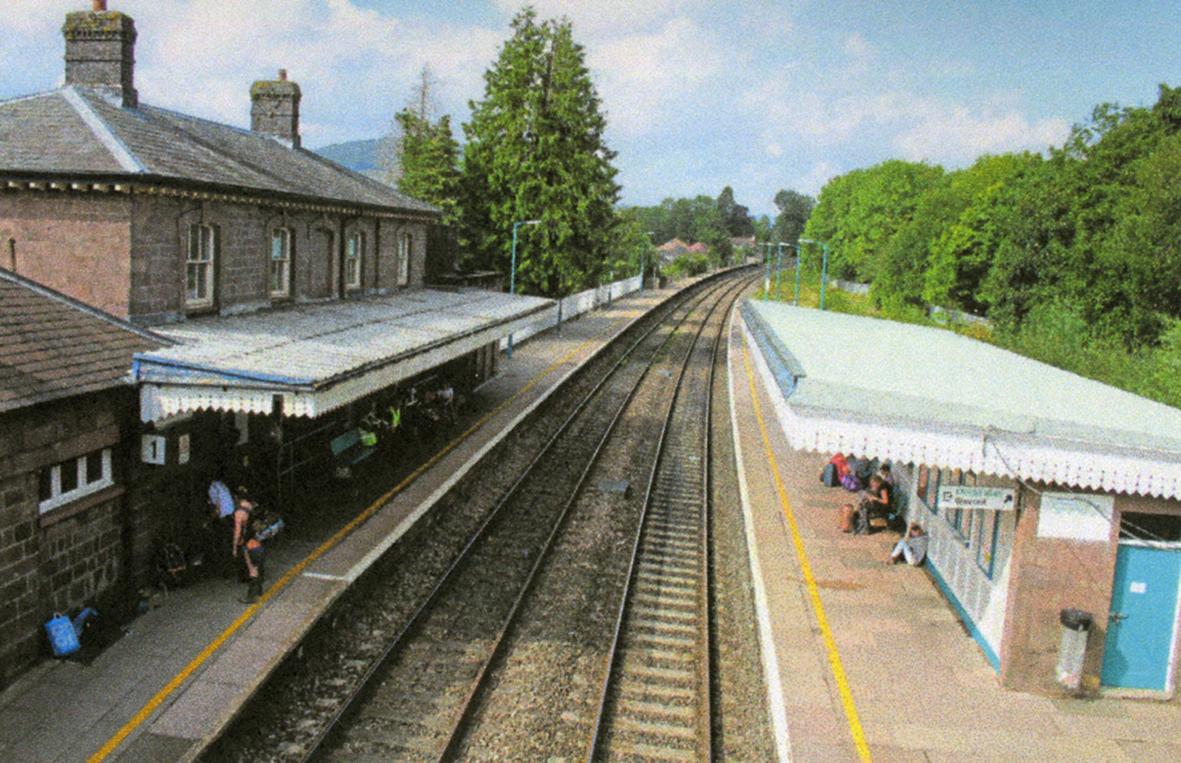

Newcomers to Abergavenny are often surprised to learn that it was once an important railway centre with three stations: the Great Western, situated to the east of the town; Brecon Road, on the former London and North Western Railway (LNWR) Abergavenny to Merthyr line; and Abergavenny junction at the point where the two lines met, north-east of the town.

Today, only the former Great Western station has survived and is still in use. A doctors’ surgery stands on the site of Brecon Road station and Abergavenny junction has been obliterated by the A465 road to Hereford.

To make sure the railwaymen of the day could live near their jobs, the authorities built houses for them in nearby streets. The present Cantref Inn was the first new building to spring up in the area, even before Brecon Road station. After that came the houses in Stanhope Street, North Street and St Helen's Road, followed by an influx of railwaymen to occupy them.

A bell hung in the station yard tolled to bring the men running to their jobs on time. It was also used to signal finishing time, and is now in Abergavenny Museum.

The book begins by describing how tramroads which were initially built in the early years of the 19th century for the purpose of conveying horse-drawn trams loaded with, coal, iron and limestone. In due course these primitive routes such as Crawshay Bailey’s tramroad from Nantyglo to Govilion Wharf and the Llanfihangel tramroad which ran to Hereford, were converted into railways.

The Act for building the Merthyr, Tredegar and Abergavenny Railway (MT&A) was passed in August 1859 and the famous ironmaster Crawshay Bailey was appointed chairman of the company. He had the drive and energy to create this railway, casting aside strong doubts that it would be possible because of the severe gradients that would be involved in creating a route between Abergavenny and Merthyr Tydfil.

Not surprisingly, the section up through the Clydach Gorge was very challenging, but John Gardner, the skilful MT&A company engineer was very skilful; and completed this part of the line in a surprisingly short time. It involved the construction of long embankments, bridges, viaducts and tunnels which enabled the line to twist and turn, but climb steadily along a ledge cut into steep slopes above the deep valley to reach Brynmawr, 1,100 feet above sea level and the highest town in Wales.

It took twenty years to overcome the numerous problems, but the line was opened section by section and eventually by June 1879, trains were travelling all the way to Merthyr High Street Station. Sadly, Crawshay Bailey had died five years previously at the age of eighty three, so he never saw his dream of building the railway all the way to Merthyr come to fruition.

Local people who travelled on this line, found it a magical experience when the autumn mists had settled in the Usk Valley, and as the Merthyr bound train climbed up through the Clydach Gorge it would gradually emerge into clear blue skies and sunshine. Looking back towards Abergavenny one could observe a sea of cloud with Skirrid Fawr and Sugar Loaf sticking up like rocks in an ocean.

People from Abergavenny remember this railway with much nostalgia, for it was a time when the town was alive with a symphony of very distinctive sounds, such as the clang of hammers, the hiss of steam, whistles tooting and wheels clattering over joints and points. It also provided considerable employment and, when railway activity in Abergavenny reached its peak, there were over 1,000 people employed in jobs associated with it.

On Tuesdays the trains were always packed with passengers, for this was market day in Abergavenny. Most of the people who lived in farms and smallholdings close to the line used the trains to transport their produce for sale in Abergavenny Market, and as a result the railway company usually had to put on at least one additional train on the line to accommodate the market-day travellers.

But to travel beyond Brynmawr in winter could be a very worrying as trains sometimes became snowbound, so passengers were marooned in the middle of nowhere. During Christmas 1927, there were 14 locomotives stuck at various points along the line.

This book is richly illustrated with both monochrome and colour pictures depicting railway scenes in Abergavenny and local people who worked in various occupations (including cleaning and servicing, locomotives; working as platelayers, signalmen, firemen and engine drivers). They all took their work very seriously and there was a great spirit of comradeship among the one thousand inhabitants who were employed on the railways.

The exciting journey from Abergavenny to Merthyr is described in great detail and many of the nostalgic pictures of these steam days have been provided by members of the Abergavenny Steam Society, who were also pleased to give advice on technical matters.

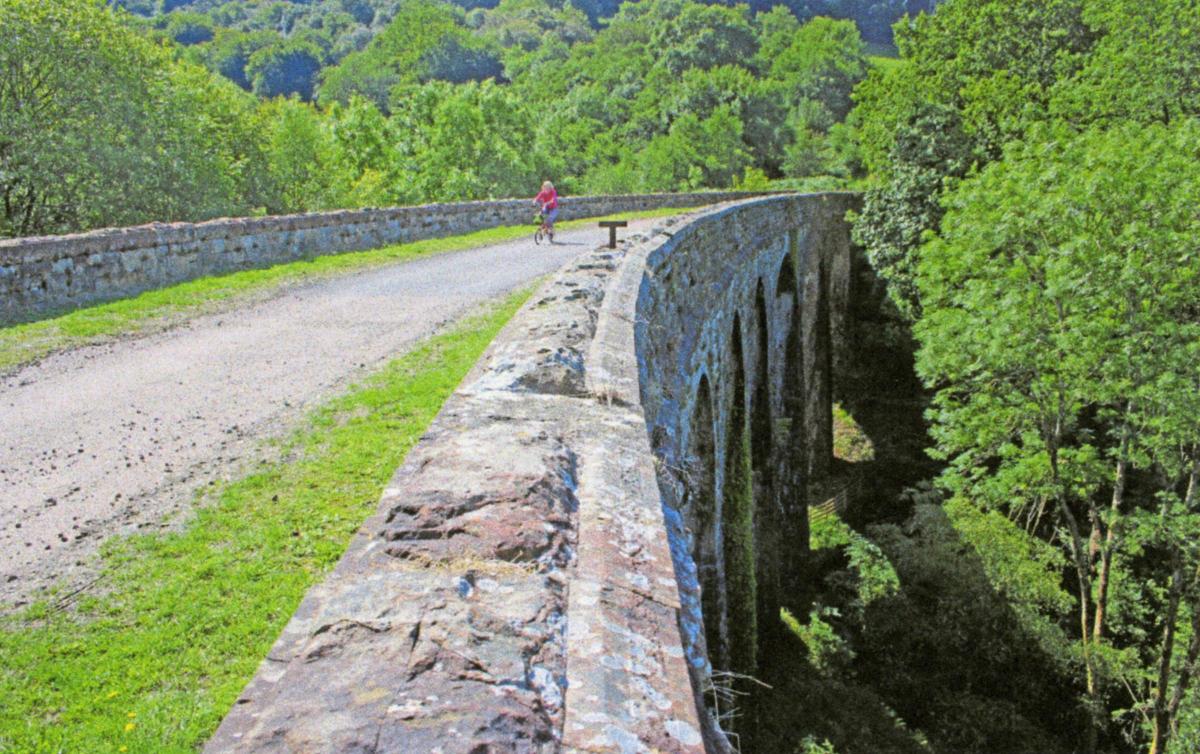

He has included present day pictures which show locations along the line as they look now compared to the time when the trains were running, giving an indication of how nature has taken over, but some structures, such as impressive stone viaducts have also been preserved as ancient monuments.

It was announced in late 1957 that British Rail wished to close the Abergavenny to Merthyr line and a meeting was held in the town by local people to prepare a case to fight this decision. Unfortunately, passenger and freight traffic by then was so small that closure was inevitable. On 29 November 1957 it was announced in the Abergavenny Chronicle that the line would shortly close, thereby saving British Rail about £60,000 a year.

In January 1958 a special train arranged by the Stephenson Locomotive Society (Midland Area) to commemorate the sad closure of this remarkable line completed the journey from Abergavenny to Merthyr and back. It was driven by George Lewis, assisted by fireman Derek Hinton and the train guard was Hubert James of Abergavenny.

Despite the cold day, large numbers of people gathered to pay their respects at all the stations and halts along the route, with everyone cheering and waving. The sad thing is that if more of them had made use of the line then it may not have been closed.

The surviving section of the MT&A in the Clydach Gorge is now an 8 mile cycle track which took more than two decades to establish and has proved an excellent facility for both cyclists and walkers, who can enjoy the beautiful scenery and also appreciate the skill of the Victorian engineers who built it in such a short time.

The Merthyr, Tredegar & Abergavenny Railway (ISBN 97814456-6328-9) is published by Amberley Books at £14.99 and is available from Waterstones and other good bookshops.

Chris Barber MBE FRGS was born in Newport and has lived in Llanfoist for the last 35 years. He is the author of 34 books which cover such subjects as: prehistoric standing stones, industrial archaeology, hill walking, local history, and the myths and legends of Wales. His many interests and achievements have been recognised with an entry in ‘Who’s Who in the World’ and he is also a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. In 2008 he was awarded the MBE for ‘Service to the Community and Tourism’.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel