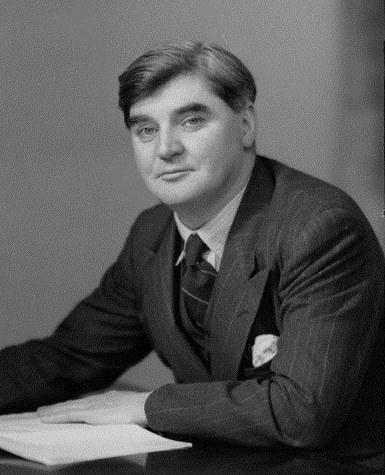

FROM coal miner to Cabinet minister, Aneurin Bevan's socialist beliefs were born from seeing at first hand - as child, adolescent and adult - the harsh realities of working class life in the south Wales valleys in the early 20th Century, and the poverty and injustices endured by so many.

He was born in 1897, one of 10 children of coal miner David Bevan and wife Phoebe, in Tredegar.

After an undistinguished school life, the young Bevan was a miner himself at 13, at the town's Ty Trist Colliery, and by 20 was an established trade union activist and head of the local Miner's Lodge.

He caused enough of a stir for the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company to seek an excuse to sack him but, supported by the South Wales Miners' Federation he won back his job, his treatment having been deemed victimisation.

Two years studying economics, politics and history at London's Central Labour College helped refine an already sharp and left-leaning political outlook.

Back in Tredegar he could not find work, but helped found the Query Club, a radical debating society with. among others his mentor and friend Walter Conway.

He remained unemployed until 1924, before a short spell at another colliery. After a further year out of work, he became a paid miners' union official.

For much of the 1920s, Bevan was a councillor at district then county level. His most recently published biographer Nick Thomas-Symonds, now Labour MP for Torfaen, believes his local government experiences have been underplayed.

"He was on Tredegar Urban District Council from 1922-28, and had two spells as a Monmouthshire county councillor, from 1928-31, and 1932-34," said Mr Thomas-Symonds.

These were periods, he said, during which Bevan learned that real power lay in Parliament and Government, but that his quest for power was not for himself, but in order that it be exercised for the good of the working class.

And when it came to the creation of the National Health Service, Bevan was convinced that councils should not be involved.

"From his local government experience, he did not want local authorities to own hospitals. He remembered how vulnerable councils are to cuts from central government," said Mr Thomas Symonds.

"He thought you had to pin the responsibility on the Secretary of State and that is in section one of the NHS Bill."

The NHS was almost 20 years away however, when Bevan became MP for Ebbw Vale in 1929, having replaced the party's sitting MP Evan Davies as the Labour candidate.

He made his mark in Parliament immediately, lambasting in his maiden speech prime ministers past (David Lloyd George) and future (Winston Churchill).

A passionate advocate of socialism and the interests of the working classes, throughout the 1930s Bevan was a thorn in the side of the Conservatives in Government and his own party's leadership.

Had the term 'firebrand' not existed, it may have been necessary to create it to describe him. He continued to challenge through the Second World War the Coalition Government - which contained among other Labour heavyweights party leader Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison (home secretary) and Ernest Bevin (Minister of Labour) - objecting to issues including the censorship of radio and newspapers, and the power of internment without trial.

Bevan was especially critical of Prime Minister Churchill during the war, the latter labelling him "a squalid nuisance".

But in July 1945 the Labour Party, unexpectedly, came to power, and Bevan was handed the job that defines him.

"Clement Attlee did not expect to win the 1945 General Election," said Mr Thomas Symonds, adding that Bevan was "a risky choice" for a Cabinet post given his fiery reputation.

"Attlee took the view that it was better to have Bevan within (the Cabinet) and creative, rather than outside and destructive."

Almost immediately, Bevan began formulating plans for a national health service, with the successful Medical Aid Society in his home town the inspiration.

The three years prior to the start of the NHS were characterised by battles within his own party, with the Conservative Opposition, and with the medical profession.

And it was from within the Cabinet that Bevan faced potentially decisive opposition to plans for a State-run service.

"Herbert Morrison (then deputy prime minister) had been leader of London County Council before the war," said Mr Thomas Symonds.

"It ran a pretty good health service, so he was of the view that councils should have the role.

"Bevan won that battle, principally because Clement Attlee came down on his side.

"Attlee accepted that if you have councils in charge it interfered with the idea of a universal service, free at the point of use.

"London might run the service well, but it had a big population and a huge tax take. Other areas did not."

Another somewhat neglected area of Bevan's Cabinet brief was housing, part of the Minister of Health's remit.

Post-war, with large areas of towns and cities bombed out, Britain needed new housing, and quickly. This proved difficult for Bevan too, hampered by a lack of raw materials and a focus on encouraging production for export rather than the domestic market.

These were big problems for Bevan, said Mr Thomas-Symonds, and he was also criticised for his vision of housing.

"That goes back to his Tredegar days, He did not like mass-produced, close together housing.

"His houses were always big. He always had in his head the miner who comes home from a shift, and they were designed in such a way that people can, for instance, bath and change in a separate room.

"He definitely did not build as many houses as demand wanted, and more could have been built if he had compromised on the design.

"But he was learning from his own experience growing up in an industrial area."

On July 5 1948 the NHS came into being, the day after Bevan intemperately and notoriously described the Conservative Party as "lower than vermin" in a speech in Manchester, a comment that was widely condemned, including from within the Labour Party.

Arguments over the running of the service continued apace. With Britain under severe financial pressure while rebuilding after the war, the spiralling cost of an in-demand NHS was debated heatedly in the Cabinet.

When new Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Gaitskell effectively capped NHS spending and introduced charges for dental care and spectacles in his spring 1951 budget, Bevan resigned - he was by then Minister of Labour - triggering a left-right split in the Labour Party that has never gone away.

Out of the Cabinet and soon in the Opposition after the Conservatives won the autumn 1951 election, Bevan's influence waned.

His chance of becoming party leader gone, "he cut a very frustrated figure", said Mr Thomas Symonds.

"He was a rumbling volcano in this period, and the Tories painted him as a bogey man."

Despite describing the ideal Labour Party leader as "a desiccated calculating machine", Bevan - while continuing to espouse the socialist cause and attack the Conservative Government - was appointed to roles including shadow colonial secretary and shadow foreign secretary in the late 1950s.

He was elected deputy leader of the Labour Party in 1959, but late that year was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He died on July 6 1960, aged 62.

"Ultimately, Bevan was someone who had a very strong socialist ideology, and always wanted to put it into practice," said Mr Thomas Symonds, who is comfortable describing Bevan as the architect of the NHS.

"There would have been some sort of healthcare system, nobody disputes that, but it is about understanding the distinct nature of the one he created, and 'architect' describes that.

"In the USA, healthcare is seen as a luxury, a commodity, rather than a right. Bevan made healthcare seem like a right, rather than a luxury."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel