‘It was a diverted stream from the Sirhowy which turned the wheel of your mill,’ I suggested to a lady of the village. Standing alongside me as I sketched she corrected me. ‘No, a stream dashed down the slope then alongside the houses to the mill-wheel. All the buildings were concerned with the business of the flannel factory, and their deeds are dated 1902.’

My mind went back to the other great ‘Flannen’ factories which I had visited at Machen, Maesycwmmer and Llanover. ‘Early and Late, by candle and lamplight and daylight the men and women laboured at their spinning and weaving, dyeing and sewing’ - that was at Machen, where “Weavers’ Row” still survives. I am sure that similar busy days were known in the seven or eight buildings of the Cwm Argoed Welsh Flannel factory.

The dyes were red and grey. I hold the theory that a red-flannel curtain separated Wales from England. At the approach of winter every mother in Wales cut and hemmed squares of red flannel and sewed tapes at the two top corners ready to fix on the chests of her little ones at the first sign of a cold.

But the flannel had to be RED. Dear old George Morgan of Ynysddu, who had seen and helped with the dyeing of the flannel at Argoed, gave me the reason for the unfailing efficacy of the red flannel. Wild Welsh mountain ponies would not drag the secret out of me.

I crossed the Sirhowy bridge and drove up to the Cwrt-y-Bella church. The name implies the court of the wolf, but I suspect that Sir Thomas Phillips transferred the name from the old farmhouse in Newport near the end of the Sirhowy tram-road.

The part played by Sir Thomas as mayor of Newport when the Chartists attacked the Westgate hotel has obscured the kindly, helpful side of his character.

As owner of the Gwrhay mines he was disturbed by the ignorance and the squalor of the district and built the Cwrt-y-Bella school and school-house, paying for the buildings, garden, equipment and master’s salary. Unfortunately subsidence rendered the school ruinous, but the schoolhouse still stands.

In addition to the school Sir Thomas made himself largely responsible for the erection of Cwrt-y-Bella church. Building materials were hauled up Hall’s tramway whence the men and women of the valley took them up to the site; one Mari Shams (James) is still named as the heroine of this project. ‘She carried twice as many slates on her head as any man, averring that she has no money, but could serve God in that way.’

The church was completed in 1857 and dedicated to Saints Phillip and James - the surname of Sir Thomas and his wife’s maiden name.

For many years the services were conducted in Welsh, and its famous vicar, the Rev Rees Jones (who gave the name to the Parson’s Bridge) used to drive his trap from his home in Blackwood, walking thence to the church where he spent his Sundays, fortified by sandwiches made by his wife and pots of tea from one of the cottages.

While generally in good condition the church needs a certain amount of repair to forestall more serious trouble.

At the ‘Colliers’ Arms’ (‘The Pick and Shovel’) Mrs Margaret Carpenter told how until 1955 the inn had been but a cider and beer house, both drawn ‘from the wood.’ She took me across the forecourt and showed me the corroded rails of the tram road which had come down alongside Nant Gwrhay. One section of rail found recently bore still the initials B.H. implying that Benjamin Hall, later Lord Llanover, had been active in the construction of the tram road.

It was the Sirhowy rail road, the earliest in Wales, of which the Grwhay line was a branch, that brought the load of coal to Newport so vividly portrayed in the splendid painting which we have allowed to go to Cardiff. Painted by John Thomas in 1821 it shows the four horses pulling the ‘drams’ of coal past Cwrt-y-Bella Farm on Cardiff Road, with top-hatted Mr Samuel Homfray sitting on the first dram and the masts and spars of ships in the distance.

My drawing, believe it or not, is of a pack-horse bridge in the centre of Aberbeeg. Its parapets are replaced by bricks and cluttered up with a mass of impedimenta which I have not included.

There it was discovered by my old friend Ali, who promptly collected me and drove me to inspect his find. As we stood admiring its graceful lines, we removed from our minds the surrounding excrescences, and saw the bridge spanning the crystal Ebbw Fach, while the sturdy figure of ‘Edmund Jones the Tranch’ crossed on his homeward way. Later again as we climbed the grand hill and turned south to Oakdale, Penmaen and Pontllanfraith we seemed to be following the footsteps of the prophet as he went about our hills and vales doing good.

Before 1853 Crumlin was a secluded hamlet comprising a few miners’ cottages, The Navigation Inn and the Company’s shop. ‘Navigation’ implied the construction of the canal, the labourers being the ‘navvies.’

Pontypool lay 5 miles away, Newport 12 mile, and at this point it was proposed to make an intersection of the ‘Western Valley Railway of the Monmouthshire Railway and Canal Company’ and the ‘Taff Vale Extension of the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway.’

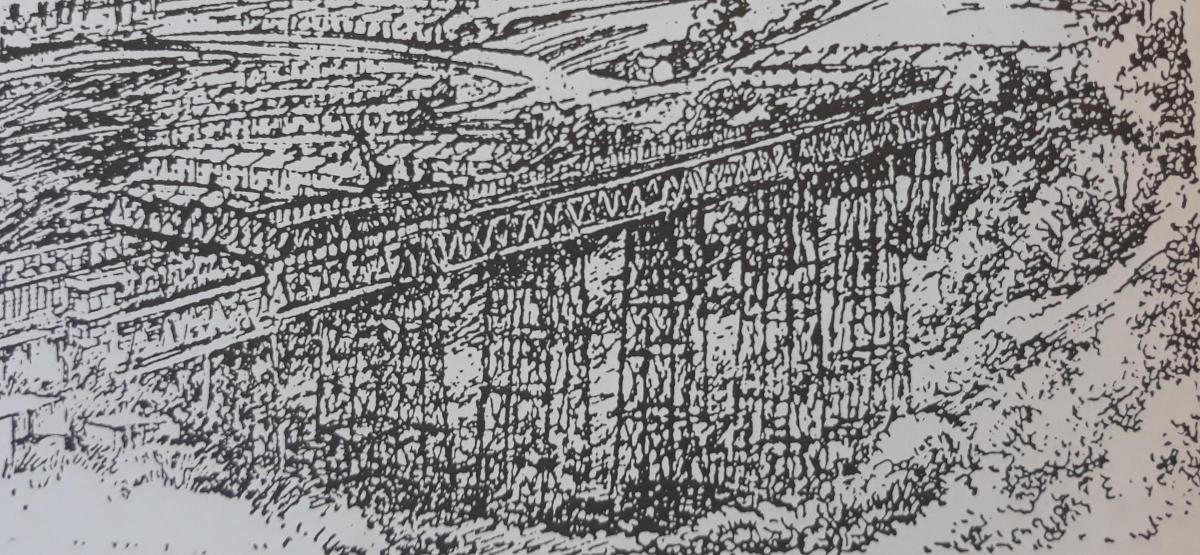

The cost of building large masonry piers at a height of over 200 feet above the valley was staggering. Several engineers submitted designs for an iron viaduct, but it was Thomas William Kennard whose work caught the fancy of the judges.

His scheme was to use open cross-braced pillars to support the 1,500 feet of super-structure; the heaviest piece of ironwork would weigh less than a ton and could be drawn up by a common windlass, sheer legs and pulleys.

One iron pier would be completed in ten weeks, while a masonry pier of the same dimensions as many months; the pressure on the foundations of Mr. Kennard’s iron piers was less than one fifth of that exerted by a stone pier.

Each pier consisted of 14 columns, of which two only were vertical.

All the others converged at an inclination of about 1 in 12, and while I am no engineer I find it absorbing to note the extreme care taken over every detail of construction, the confidence in the cross-braced pier construction - the first of its kind - the calculation (confirmed in use) of the strains on the girders, and the clever arrangements made to permit the expansion due to variation of temperature.

I cite as an outstanding example of this variation the records dated February 12, 1861, and August 27 in the same year when the temperatures of the girders varied from 32 degrees Fahrenheit to 98 degrees, and the length of the girders increased by two and three-quarter inches.

l This is an extract from Hando’s Gwent, Volume One, edited by Chris Barber.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here