This is an extract from Hando’s Gwent, Volume One, edited by Chris Barber and reproduced with Mr Barber’s permission.

Steps lead up from the courtyard to the outhouses and the stables, where I took the chance of sketching the famous oak columns, traditionally from a wrecked Armarda galleon and erected here by Spanish prisoners.

Away beyond, stretch the remains of the chestnut avenue - magnificent trees, rising like fluted stone columns, almost as old as the house. In the chestnut avenue is a deep well to which is attached a memory. Long ago the beloved and only son of the house drank from a pewter cup, was poisoned and died. Frantic with grief, the father collected all his pewter, which was never seen again.

Within the court, all is well-proportioned and beautiful. Colonel Hopkinson and his lady have furnished their home with their own treasures, and as we walked around the rooms the family portraits seemed to greet us. One Court beauty vied with another, but for sheer loveliness I should choose the superbly painted Lady Congleton, arrayed as maid of honour to Queen Victoria.

The priceless seventeenth-century rose ceiling displayed not only Tudor roses and oak leaves but also the queerly decorated fleur-de-lis like those I had noted in the village church. Doubtless the Arnolds had the right - from Ynyr, king of Gwent - to use the fleur-de-lis, but by what dispensation could they cause acorns - if they are acorns! - to spring between the petals?

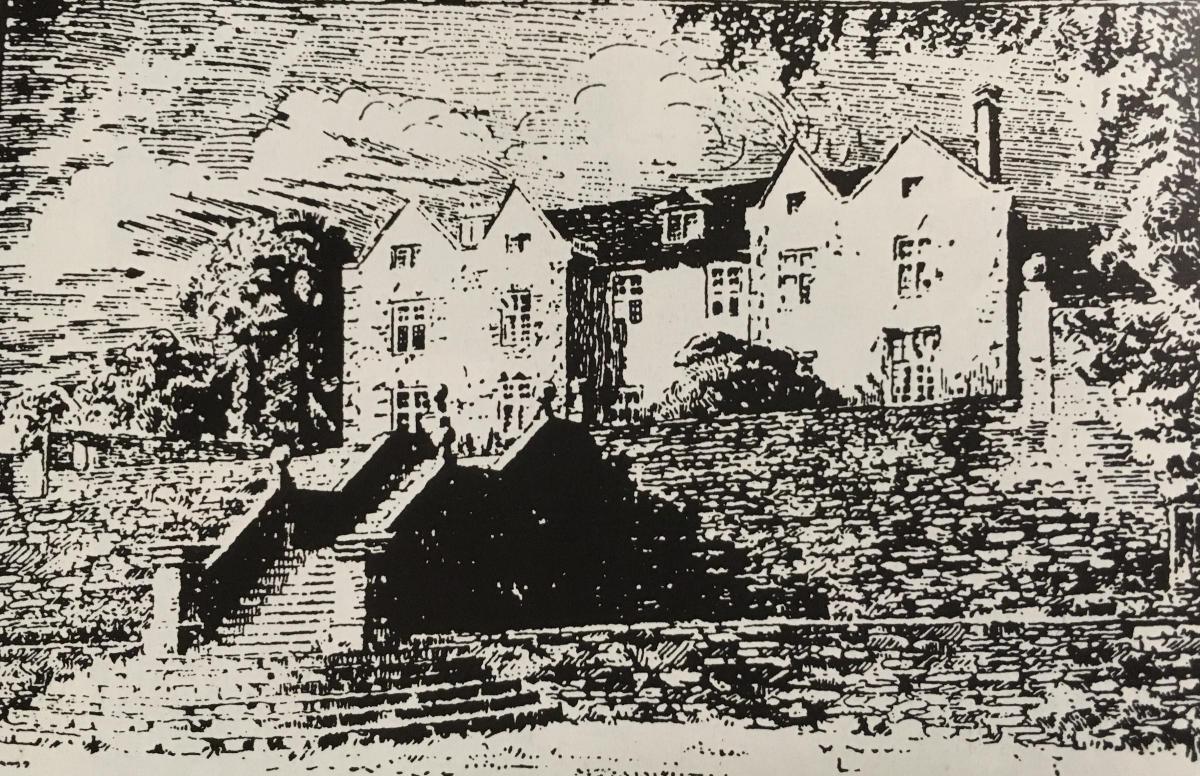

After my inspection of so many Monmouthshire houses it was pleasant to place Llanfihangel Court 'in period.' The earliest portion of 1559 is the east wing and the reminder is of the early seventeenth century.

Of the many splendid rooms I must note the 'White Room' where once was seen 'a little man with green eyes' and the King's Room where Charles I slept. The head of the bed on which he slept is preserved and bears the inscription.... 'KOFIA DY DDECHRE' (Remember thine origin).

I was glad to see again the fine coat-of-arms of Charles I painted on wood and decorated with mother of pearl, which young Mr Bennet had discovered reversed behind a wall panel.

One of the most characteristic rooms is 'Queen Elizabeth's Room', in which an imposing four poster bed with an ornate canopy may have rested the much travelled queen. Of the dramatis personae I need but record that the manor was held in the days of Henry VI by Thomas ap John ap Gwilyn of Wernddu, that a descendant Rhys Morgan built the east wing and that by the way of the Earl of Worcester the Court was sold to the Arnolds.

It was John Arnold of Llanfihangel, who made himself famous - and infamous - by his fanatical persecution of the Roman Catholics who dared to celebrate Mass in the little Llanfihangel chapel on the Skirrid summit. An interesting comment is Coxe's note, written a century later:

"To this place many Roman Catholics in the vicinity are said to repair annually on Michaelmas eve and perform their devotions. The earth of this spot is likewise considered as sacred and was formerly carried away to cure diseases, and to sprinkle on the coffins of those who where interred."

Turn left at the Skirrid Mountain Inn and bear left at the bottom of the hill by Bridge Cottage to follow the scenic route through the Vale of Ewyas, past Cwmyoy and on to Llanthony, Capel-y-Ffin the Gospel Pass and perhaps down the other side of the Black Mountains to reach Hay-on-Wye.

Seen from the road, Bridge Cottage has changed little during three centuries. Slates replace the old stone tiles, the chimneys are now of bricks, and the walls have been "rendered." yet the general air of demure assurance demands that we shall cherish it. I suspect that the building of the old bridge at the ford over the Honddu accounted for the sitting of the cottage. This would be an appropriate origin for the home of a bridge builder and roadmaker.

Soon after turning into the Llanthony valley you will descry amid the heights ahead a weird bulbous summit. That is Cwmyoy landslide, a mighty fragment torn away from the Hatterall ridge. Seen from the front, part of the hilltop is shaped like a yolk, accounting for the name 'Cwmyoy' - the valley of the yolk; seen from afar, the landslide itself seems like an immense boil on the shoulder of the Hatterrall.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here