THE ARMISTICE

THE Fighting Has Ceased On All Fronts.

This headline greeted South Wales Argus readers on Monday November 11 1918, another proclaiming 'Germany's Submission' and a third that there were 'Rejoicings Everywhere'.

With good reason. Four years, three months and one week after Britain declared war on Germany - a period during which millions of lives were lost, on the battlefields of France and Belgium, on land, at sea, and in the air - the guns finally fell silent.

A war our political and military leaders had expected with some confidence would be over by Christmas 1914 had dragged inexorably on, neither side able to dominate the other long enough to build and sustain the momentum required to inflict defeat.

Towns and villages across the Western Front, and many unfortunate enough to be centre stage in myriad other theatres of war, were obliterated. Vast tracts of countryside and woodland were destroyed too, the land over which armies fought stripped of pretty much everything other than the blasted ground under soldiers' feet.

The end had been coming for months. A massive German offensive in spring 1918 threatened to sweep all before it, with mounting fears of fighting on what would be left of the streets of Paris, after the capital came within reach of the enemy's new, more powerful artillery.

However, though troops on both sides were demoralised and exhausted by seemingly endless conflict before that offensive began, once again momentum shifted.

There was mutiny in the air among German ranks, stoked by similar unrest in the armies of their Austro-Hungarian allies. With Britain and France fighting back, and more American troops joining them, the German offensive ground to a halt during May.

The Germans continued to try to make inroads, but another foe, the mass killer and debilitator that was Spanish Flu, had began to circulate.

All sides lost soldiers to the virus, but German and Austro-Hungarian forces appeared the hardest hit.

On July 18, the Allies launched a major counter-offensive that ultimately proved decisive, but only after savage resistance. This was slow, hard, brutal progress but Germany's allies were failing all over the map and defeat became inevitable.

Through late summer and early autumn, the South Wales Argus, like newspapers across Britain, carried daily reports of Allied advances, of territory recaptured, seemingly decisively, after repeatedly swapping hands in the earlier ebb and flow of war .

Germany made several attempts from late September to strike peace terms, rebuffed as being too lenient. Finally, the end came in a railway carriage in the Forest of Compiegne, northern France, in November.

The Allies' terms to end hostilities were put to German negotiators on Friday November 8. They were rebuffed as being too severe, the demands adding up to complete demilitarisation of Germany, with virtually no guarantees in return.

The Allies were in no mood for negotiating, German protests fell on deaf ears, and with the situation in Germany and on its front lines worsening, they reluctantly put pen to paper shortly after 5am on November 11. The armistice came into effect at 11am that day.

Technically it was just a truce, though no-one doubted that this was the end of the fighting. The armistice had to be formally prolonged three times however, ahead of and during the Paris Peace Conference negotiations that led to the June 1919 signing of the Treaty of Versailles between the Allied powers and Germany.

Peace was only formally ratified when that treaty became effective on January 10 1920.

AND THE ARMISTICE THAT WASN'T

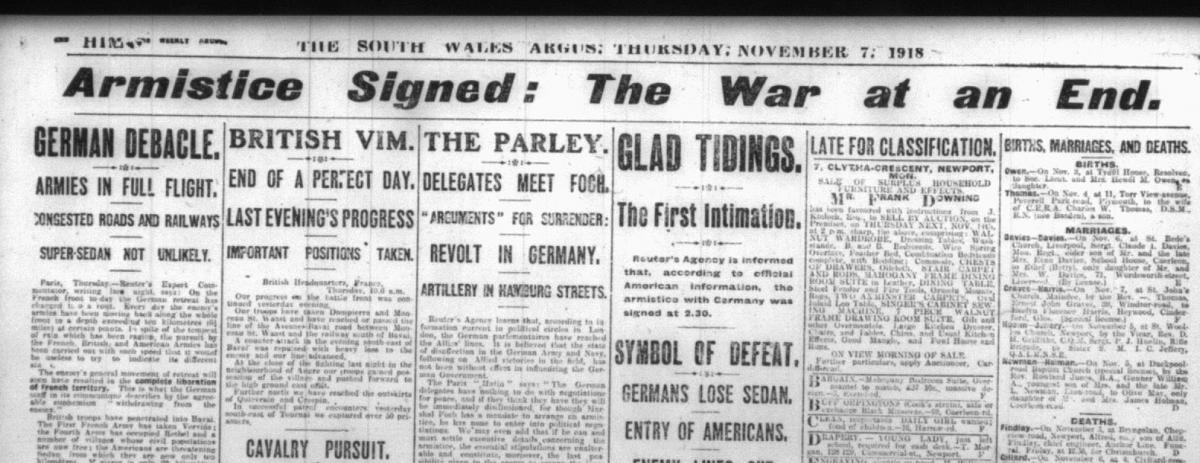

ON Thursday November 7, the South Wales Argus declared - Armistice Signed: The War at an End.

Under the sub-headline 'Glad Tidings' the newspaper reported Reuter's having been informed that, "according to official American information, the armistice with Germany was signed at 2.30".

Whether am or pm was not stipulated, but many British newspapers, eager to impart the good news, took the information as fact, triggering spontaneous outpourings of joy across the land.

Alas, it was not true. The armistice had not been signed.

A later edition of that day's Argus carried in its 'stop press' column, this announcement: "The Armistice. Is it true? A later message suggests that the statement as to the signing of the armistice is premature."

Next morning, that prematurity confirmed, this and other newspapers went on the defensive, apologising without really saying sorry, for spreading false hope.

The Argus comment column of Friday November 8, deploying the unblinking misogyny of yore, intimated that this and other newspapers had been seduced by the temptations of 'Dame Rumour'.

Taken in by the sight of this 'lying jade' and her seemingly authentic 'robes of truth', they had been undone by her deceit.

To translate: Embarrassed male editorial decision-makers sought to humanise and so blame - and of course it must be a woman - the rumour that the armistice had been signed. The plain fact is, they got it wrong.

They explained that had been told the Allies and the Germans were talking, and "it was not a case for quibbling".

"The pity of it is that the newspapers wasted good effort and the public good emotion", the Argus concluded somewhat sheepishly, before seeking to assure readers that peace really was just around the corner.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel