As we head towards the 180th anniversary of the Chartist Uprising, PETER STRONG describes John Frost's Newport

NEWPORT in the 1830s was a town on the up.

It was riding on the crest of the wave that was the Industrial Revolution.

As the iron and coal industries in the Gwent valleys grew, so Newport grew with them.

Its population had grown tenfold to about 10,000 since the time of John Frost’s birth in 1784.

MORE NEWS:

- Newport's fundraising cobbler Kelvin Reddicliffe prepares to retire after 50 years of service

- Newport teen's exam result is best in the world

- Dealers who ran Newport and Torfaen drugs network jailed

Some rode the wave and prospered but others found themselves drowning in a sea of poverty and hardship, symbolised by the new workhouse near the top of Stow Hill, completed in 1838. So Newport was a town of contrasts.

Alexander Cordell described it in the poetic language which were a feature of his novels:

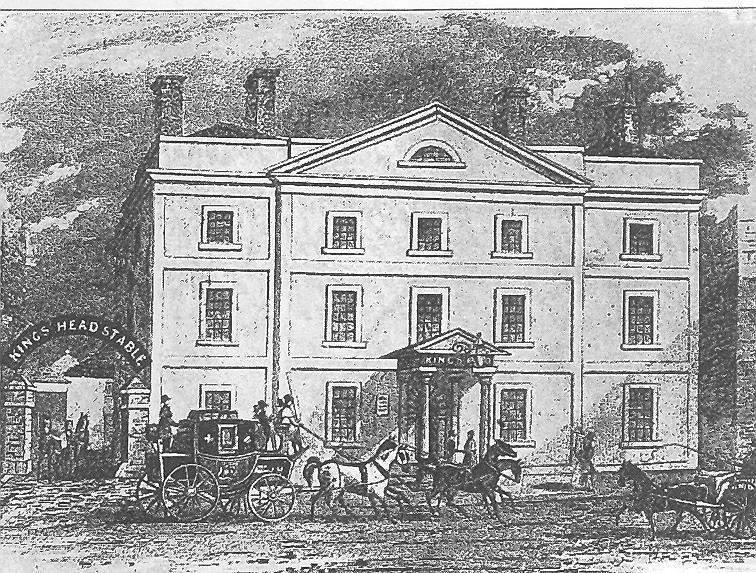

‘…that untidy, brawling 19th century Newport, a town of violence and political unrest … when ladies lifted their skirts above the littered garbage, and maddened bulls roared their defiance at the baiting mob around the King’s Head Hotel; when painted women slanted their eyes at tipsy sailors in the docks and urchins thumbed their noses at the carriages of passing gentry… The black and gold of dozen tributaries pouring down from the gulches of the Welsh valleys into the town’s greedy maws… Here iron, coal and coke, limestone and pit props and a score of other commodities carved the channel to the ports of the world – sent in the cause of commerce by magic names, the tyrants of the Industrial Revolution – the Crawshays and the Guests and the Baileys.’

As a local shopkeeper commented: ‘Newport is rapidly rising in trade, improvements and importance.’

A letter to the Monmouthshire Merlin newspaper observed: ‘Newport is undoubtedly the metropolis of the trade and commerce of this important district. I know of no place where nature has been more lavish with her gifts.’

Situated near the mouth of the Usk, its wharves were in an ideal position for serving the valleys.

Every week the local press gave details of its numerous exports including iron and coal to Normandy, tin plate to Bristol, iron to Malta and beer and porter to Carmarthen.

In the other direction came bacon and flour from Bristol, hopes and potatoes from Gloucester, cattle and pigs from Cork, timber from Chepstow and iron ore from Cornwall.

In 1835, to the sound of church bells and canons firing and townsfolk cheering, the first sod had been dug in Newport’s first dock (Town Dock), itself a declaration of confidence in the future of the town as a major port. The Merlin, which had shown its own confident by moving to Newport from Monmouth a month later, declared that Newport was ‘the Liverpool of Monmouthshire’.

The built-up area had stretched east of the Usk to Clarence Place but Maindee and, west of the river, Malpas (not yet part of Newport) and Shaftesbury were still open fields.

New streets were being mapped out.

Commercial Road linking Newport to Pwllgwenlly had been constructed and a grid laid out which would before too long turn the open fields between the two into rows of houses.

In spite of their poor condition, muddy in wet weather and dusty in dry, the streets were centres of activity, not always to the liking of ‘respectable citizens’.

One complained of obstructions caused by Punch and Judy shows and ballad singers.

While English was the main language, particularly of business and trade, Welsh was commonly heard, particularly on market days, when the rural population converged on the town to shop from the multitude of stalls which blocked the High Street.

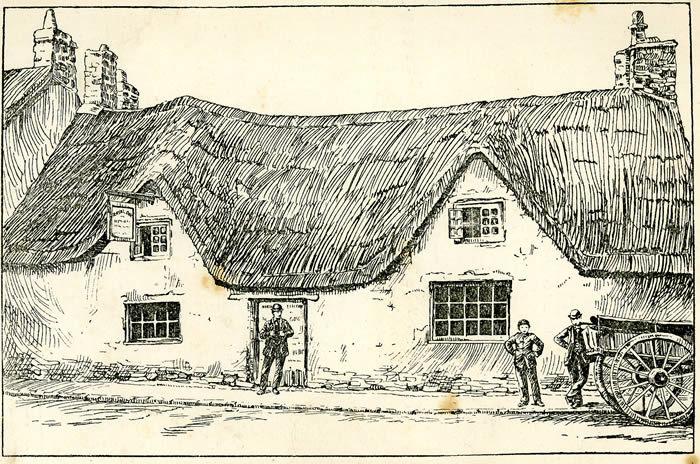

The Irish population was already well established and in 1839 celebrated St Patrick’s Day with a march through the town and an ‘excellent dinner’ in the Bush Inn (well known as a Chartist meeting place).

Rapid growth brought many problems.

It was not a pretty town. One visitor called it ‘a confused mass of jumbled up buildings without any uniformity or architectural design.’

Friars Fields, between the town centre and the river, was an area of crowded slums, where whole families shared a single room and whole streets a single toilet.

It was notorious as a hive of disease, crime and ‘houses of ill fame’.

There were serious concerns about the behaviour of the lower classes.

A few weeks after the Rising, Colonel Considine, commander of the troops sent to the area, called Newport: ‘a vile town in which I think the lower classes are of the very worst description.’

A resident complained of the ‘the low and foul-mouthed rabble, who are ever to be found

congregated on the corners of each of the streets’, while another berated the ‘rough-shod idlers who dangle their lazy lengths upon the parapet wall’ of Newport bridge, ‘stretching out their heels to be cleaned by the dress of every passer by.’

The town’s nine chapels did their best to keep the working classes on the strait and narrow, and St Mary’s Catholic Church was under construction, but it seems that until after the Rising, little else was being done

One correspondent complained that ‘no literary or scientific institutions exist in the town.

'In a town like this, abounding with working men, it is indispensable.

'It would win them from the low and grovelling pursuits. Now, when his toil is done, the labouring man has no other place of resort than the common pot-house, where his morals become corrupted.’

A town of extremes undergoing rapid change; such was Newport in 1839 – a powder keg waiting to explode.

This is part of a series of features marking the 180th anniversary of the Newport Uprising.

- Newport Rising Festival remembers Chartists' fight for democracy

- What did policing look like in the days of the Newport Uprising?

- School pupils continue the Chartist legacy 180 years on

- The Newport Uprising in the words of the people who saw it happen

- Newport's Chartist landmarks

- From traitors to heroes - how attitudes to the Chartists have changed

- Take a look inside Newport's historic Westgate Hotel

- Political figures pay tribute to 'pivotal moment in our democratic history' as Newport Rising anniversary approaches

- Remembering Alexander Cordell, the novelist who inspired so many to explore Newport's Chartist history

- The story of the Westgate Hotel and its central role in Chartist Uprising

- From shop windows and scrapyards: The Chartist display in Newport Museum

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel