Nearly 160 years ago 142 men and boys from Risca were killed. ELIZABETH BIRT looked back at the Black Vein Colliery disaster of 1860

TODAY - Sunday, December 1, is 159th the anniversary of the 1860 Black Vein Colliery disaster, which was at the time the worst mining disaster ever in Wales, and the second worst in the UK.

The pit had opened circa 1843, and had quickly become known as ‘the death pit’ among workers and residents of the area due to the number of deaths in a short period of time.

MORE NEWS:

- Locked up: The paedophile, killer, brawlers and con man jailed

- Mental health nurse Rebecca Topczylko-Evans jailed for defrauding Gwent's health board

- Thief who drove off without paying for petrol 23 times avoids going to prison

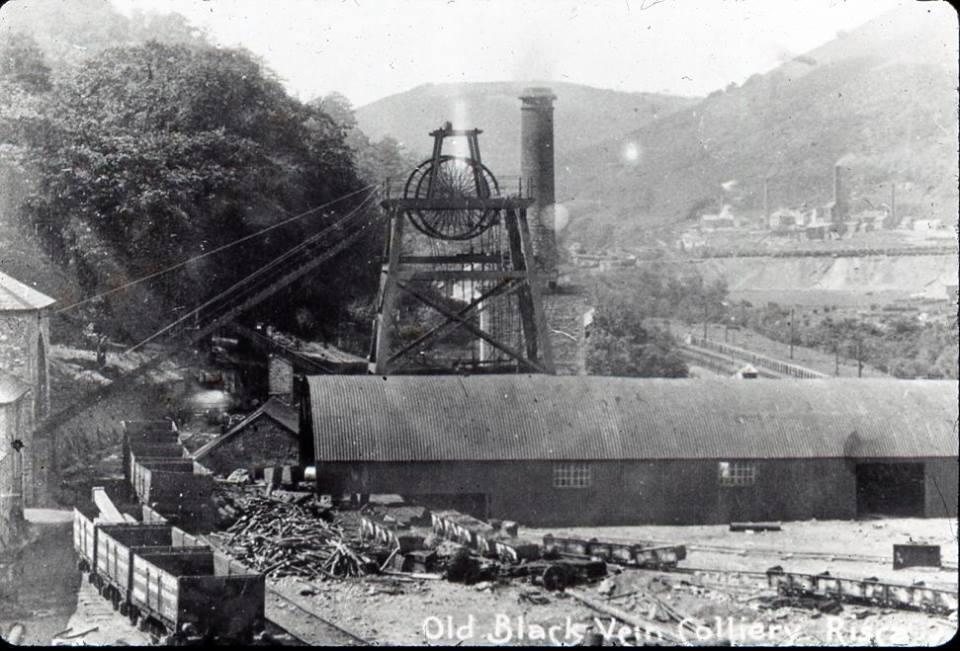

Black Vein Colliery pictured in 1900

On December 1, 1860, an explosion happened in one of the districts just off the main roadway at the bottom of the colliery.

The force of the blast was tremendous and brought down several huge falls that blocked the ventilation – the new mechanical ventilation system was only brought in two years earlier in 1858 – this caused the after-damp to be trapped in the area, leading to the deaths of the majority of the victims.

The disaster, in which 142 men and boys died, was recorded in the Argus' our forerunner weekly paper the Monmouthshire Merlin on December 8, 1860. A reporter from the paper was at the scene and “witnessed a scene of horror which battles description, and which, could it be faithfully depicted, would harrow the feelings of the reader to a degree painful in the extreme."

They wrote: “Amid the alarm and confusion prevalent in the neighbourhood of the catastrophe, the information obtainable at first was necessarily of a rather meagre character; but subsequent investigations have shown that the calamity was one of a fearful and an overwhelming character.

The Black Vein memorial ground at Greenmeadow in 1979

“It is customary for the workmen at the Black Vein pit to commence their labours at an earlier hour on Saturday morning than on other days of the week, as they leave work soon after dinner. This rule was pursued on the morning of the explosion. The workings having been previously examined, at five o'clock, about 200 men descended to their dangerous, and, as it proved to many, fatal avocation.

“For some time nothing occurred to induce a supposition that anything unusual had taken place, neither in reality had there; but about half-past nine o'clock a report was heard, ominous in character, from the mouth of the pit, creating instant alarm and intense anxiety upon all hands.

“Too well was the dread signal understood and means were adopted with the utmost promptitude to ascertain the extent of the calamity. Those of our readers at all acquainted with these matters, know too well the difficulty and danger which are always presented on such an occasion, and with what caution it is necessary to proceed to prevent a still farther sacrifice of life. All was, however, done that was possible.”

The 'x' marks the location on the Black Vein site of a capped shaft. The picture was taken in 1979

The article also outlined how, just a week earlier, the watch manager had punished one of the workmen for breaking the law and endangering the lives of his colleagues by having an uncovered flame. It is thought an uncovered flame may have been the cause of the explosion, although it is uncertain.

READ MORE:

- Call for donations to fund a memorial at the site of several mining disasters

- New memorial stone dedicated to the victims of tragic mining disaster is unveiled

- Mining disaster victims commemorated with stained glass window at church

The article continued to describe the efforts of the local community, and those in the mining community from further away, who stepped in to help with the task of recovering the bodies and treating the injured. The efforts of Dr Robathan who was on the scene for days to help not only those who were trapped, but those who bravely went into the mine to rescue them, were also outlined.

He was the surgeon of the works and, along with Pontymister surgeons Dr. Godwin and Dr. Evans, one of the three were present at each time throughout the entire operation.

Some of the devastating stories of families who had lost multiple members, and some of people who survived, were reported.

Three members of one family were highlighted, a 32-year-old man and his two sons, aged just 10 and 12 all died from the damp.

A survivor told the reporter on the scene about the sensation of suffocation and a feeling of delirium that overcame him. Most people working in the upper part of the pit escaped, although many reported that it was with difficulty and some didn’t know how.

One lucky tale came from Moses Short - he was working in the mine with two of his sons. The article reported: “Moses Short was working with two of his boys; he caught them up, and by one of those amazing efforts men make in danger, he carried them both into what proved to be safety. He then felt himself failing and had to drop one in the agony to save his own life and got out. To his delight the little fellow, after a time, was brought out alive. He is a Sunday scholar, and his first exclamation on reaching the top was ‘thank God, I'm alive’."

Another worker was down the pit with his son at the time. They were running towards the exit when the father could feel himself weakening. It is said he told his son to put his cap over his mouth and lie down with him. The father had quietly crept further back into the mine, knowing he was about to die, and his son tried to feel about for his father, but when he couldn’t find him, he managed to make it out to safety.

Some of the survivors were saved by chance circumstances. Samuel English was about to go down with his friend at the moment of the explosion. He turned back to get a candle while his friend went on down. His friend died, but he survived.

Joseph Hele was working down the mine on the Friday night shift and was meant to continue working there through part of Saturday too. It is unknown why he was sent up with the night shift workers at the end of their shift, but it saved his life. By the time he arrived home, the explosion happened, and his two brothers died.

Moses Banfield was another lucky one by arriving too late to go down with the day workers.

The 142 who died were not just killed in the explosion - but some who bravely went in to help with the rescue efforts also lost their lives. Fanny English’s husband Edward was an overman who escaped the first effects of the explosion but felt bound to go back and help. He never returned alive.

A memorial plaque was rediscovered by offenders on a community payback scheme in 2010 at Greenmeadow, overlooking the site of the colliery. There were 12 people buried there.

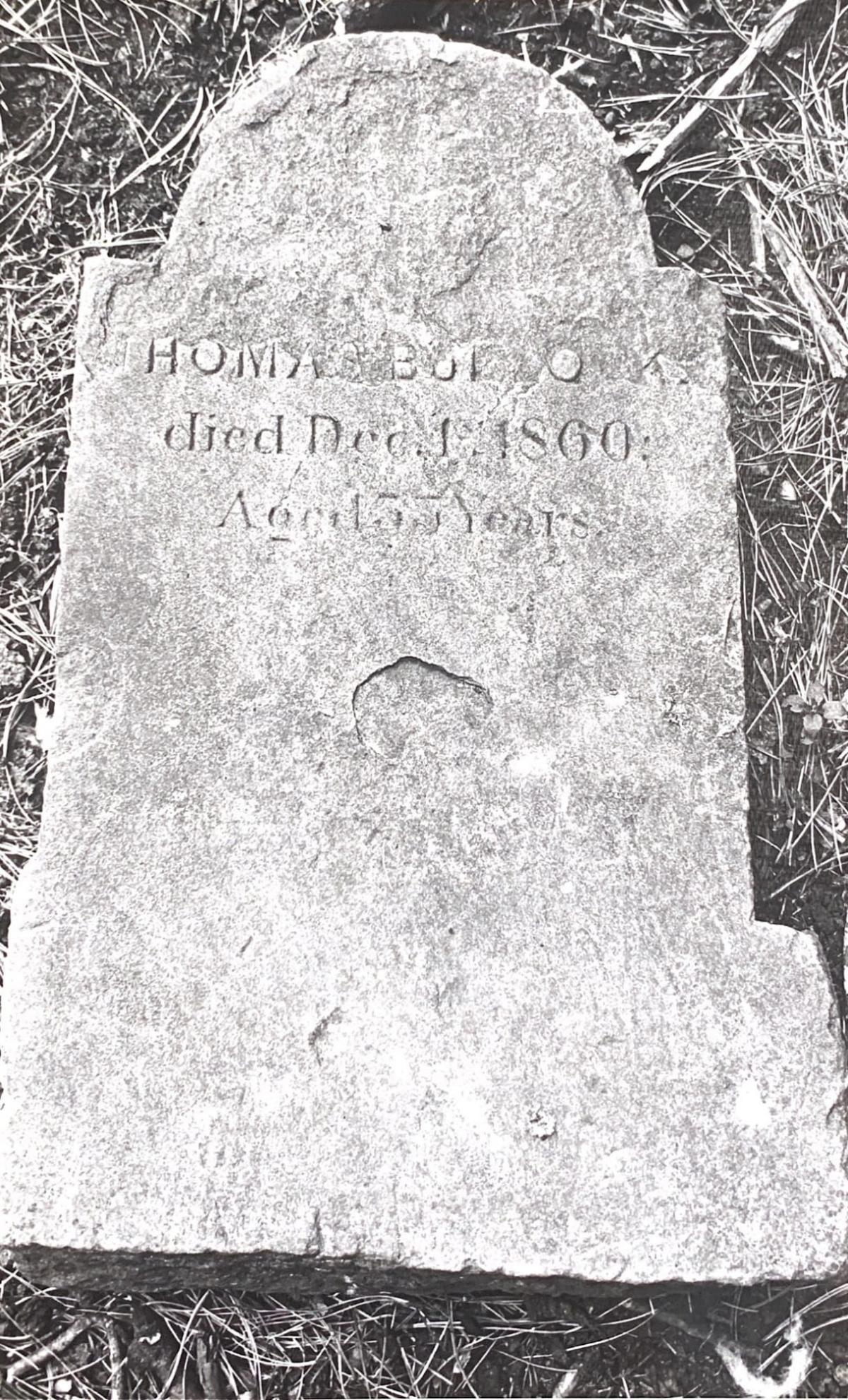

One of the victims of the disaster, William William's headstone that was at the Greenmeadow burial site in 1979

Most of the victims were buried in St Mary’s Churchyard, Risca. More victims were buried at Old Moriah, Bethesda and Bethany chapels, St Michael and All Angels at Lower Machen, St John’s at Machen, St Tudor’s and New Bethel in Mynyddislwyn.

There were also burials at Bedwellty, Rogiet, Trevethin, Thomastown, Michaelston super Avon, Llanfabon and Pyle and Kenfig.

It is 159 years since the incident but it, and those who died, have not been forgotten by the community.

Each year on the anniversary of the disaster, a service is held at one of the burial locations by the Black Vein Miner’s Memorial Society as descendants of those who died gather to remember their relatives.

MORE NEWS:

- The Newport shop with a selection of unique gifts perfect for Christmas

- City's only school for autistic youngsters to expand

- First tenant announced at former city centre sorting office

The society regularly tend to the Greenmeadow burial site, having a new memorial placed and making sure that the site is in a good condition.

The 2018 Blessing ceremony was attended by members of the Black Vein Miners Memorial Society, Reverend Martin Evans, and The Deputy Mayor of Caerphilly CBC, Cllr Julian Simmonds, Picture: Stephen Lyons

They have also raised enough funds to have a memorial plaque placed at the bandstand in Waunfawr Park, Crosskeys to commemorate those who died in the 1860, 1880 and all the other disasters and deaths that happened at the Black Vein and Risca New Mine collieries at the location of the mine entrance.

This ink drawing is of the 1880 disaster at the nearby Risca New Mine. This came 20 years after the 1860 disaster at Black Vein and at the front of the carnage is two widows, with an older lady who lost her husband in the 1860 disaster comforting a widow of the 1880 one. This image formed the design of the memorial plaque that is going to be installed in Waunfawr Park next year

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel