IN THE early hours of February 26, 1918, the hospital ship HMHS Glenart Castle left Newport and steamed down the Bristol Channel.

Its destination was Brest, in north western France, where it would pick up wounded soldiers from the Western Front and bring them home for treatment.

On board the Glenart Castle were nearly 200 people - the captain and Mercantile Marine crew, medical staff of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), chaplains, nurses, and patients.

At 4am, the hospital ship was off Lundy island, in the Bristol Channel, when disaster struck. According to newspaper reports at the time, the ship’s helmsman noticed a suspicious light in the water.

He sounded the alarm for a lifeboat drill, but before anybody could react, there was an almighty explosion. A torpedo, fired from a hidden German U-boat (submarine), blasted a hole in the ship’s hold.

“Almost everybody aboard was asleep at the time, and most of the men tumbled to the deck in the scantiest attire,”, the New York Times reported a rescued crew member as saying

“Probably nine out of every ten were barefooted. The men assigned to the starboard lifeboats found them useless, either the boats or the davits (cranes) being smashed by the shock of the explosion.”

In rough seas, those on board rushed desperately to leave the sinking ship. The torpedo strike had destroyed many of the lifeboats, and as the ship started to slip below the water, the survivors struggled to launch the remaining craft.

A total of 162 people died when the Glenart Castle sank, including 11 from Newport - William Attwood, Frederick Clifford, Edgar Hopkins, John R Jackson, Edward James, William John Jenkins, John Clifford Kennie, Thomas Macaulay, Frederick Charles Rice, Henry John Wood, and Wilfred Sidney Wyatt.

The hospital ship (above) - which should have been protected by international treaty - had, according to eyewitnesses, been sailing with Red Cross lights, marking it as a non-military vessel.

People reacted to the sinking “with horror and distaste”, said Newport historian Andrew Hemmings.

“There was outrage at the time, because of the number of casualties that were female nurses and - as far as British sources are concerned - there were no weapons on board,” he said.

Reporting from the time suggested the Glenart Castle had been in Newport for three weeks of repairs prior to the night of the U-boat attack.

“Newport and the Bristol Channel ports weren’t close to the front, but it wasn’t unusual [for military and hospital ships to be docked in the area],” said Mr Hemmings.

“Ships used to come up the channel, bringing the wounded back to Britain.”

The Glenart Castle, built by Harland and Wolff in 1900, had originally been named Galicia. The steamship was converted to a hospital ship after the outbreak of the First World War, and was clearly marked on its sides with the sign of the Red Cross, and was illuminated brightly at night.

The day after the sinking, eyewitnesses gave evidence at the Admiralty Court of Inquiry.

John Hill, who was just off Lundy aboard the fishing trawler Swansea Castle, said: “As we were steaming along I look around with the glasses and away in the starboard rigging I saw the hospital ship with green lights all around her - around the saloon.

"She had her red side lights showing and mast-head light, and also another red light which I suppose was the Red Cross light.”

“When she got right ahead all her lights went out. When the lights went out, I turned around with the glasses in my hand to see that she went clear of us and I saw the vessel in the moonlight. Every light on board had suddenly disappeared.

"Of course that made me think that something was wrong and I remarked to my mate at the wheel that it was funny.”

The fisherman looked around and saw “something in the water” that “looked like a Noah’s Ark”. It was the German submarine, UC-56, slipping away.

German submarine UC-56 in Santander, Spain, May 1918. Picture: US Library of Congress

The hospital ship sank within minutes. Of those on board the Glenart Castle, 93 crew members died, including Captain Bernard Burt. Others who perished included 47 RAMC officers and men, eight female nurses, and two army chaplains.

Just 32 survivors were rescued, picked up by the fishermen, a French schooner, and an American destroyer.

READ MORE:

- Lovell's Athletic - the story of Newport's lost football club

- When swimmers raced in the River Usk at Newport

- Amazing story of Newport Antarctic stowaway Perce Blackborow

One survivor, Thomas Casey, told the Admiralty Court: "There was such a heavy sea running that I doubt if the other boats have lived in it."

As news of the U-boat attack broke, public outrage over the sinking was exacerbated by rumours that the German submariners had opened fire on survivors as they escaped the ship.

The New York Times carried reports, originally from the Liverpool Evening Express, that the body of a Glenart Castle officer had been found with two gunshot wounds. He had been wearing a lifebelt.

“While there have been no reports that the Germans fired on the escaping crew of the hospital ship at the time of the torpedoing, this discovery leads to the belief that an attack was made subsequently on some of the boats,” the NYT reported on March 11, 1918.

But Mr Hemmings said there were doubts over these allegations.

“It was the survivors and the fishermen who alleged this,” he said.

“There’s no conclusive evidence. My own view is that [the claims] were part of the reaction to the horrific torpedoing of an unarmed ship, and the killing of the nurses.”

The sinking of the Glenart Castle provoked a furious reaction from the British Admiralty, too. After the war, the admiralty tried to charge the U-boat captain, Kapitänleutnant (Captain Lieutenant) Wilhelm Kiesewetter, as a war criminal.

Mr Hemmings said the submarine captain landed in Britain at the war’s end and was promptly arrested and locked up in the Tower of London. But without any legal grounds for trying the captain during the Armistice period, the admiralty had to let him go, and he was returned to Germany.

In a cruel twist of fate, Cap Lt Kiesewetter was once again enlisted as part of Adolf Hitler’s Kriegsmarine (Navy) during the Second World War. Records show that at the age of 62, he was called up to command the UC-1 submarine, though it completed no operational missions.

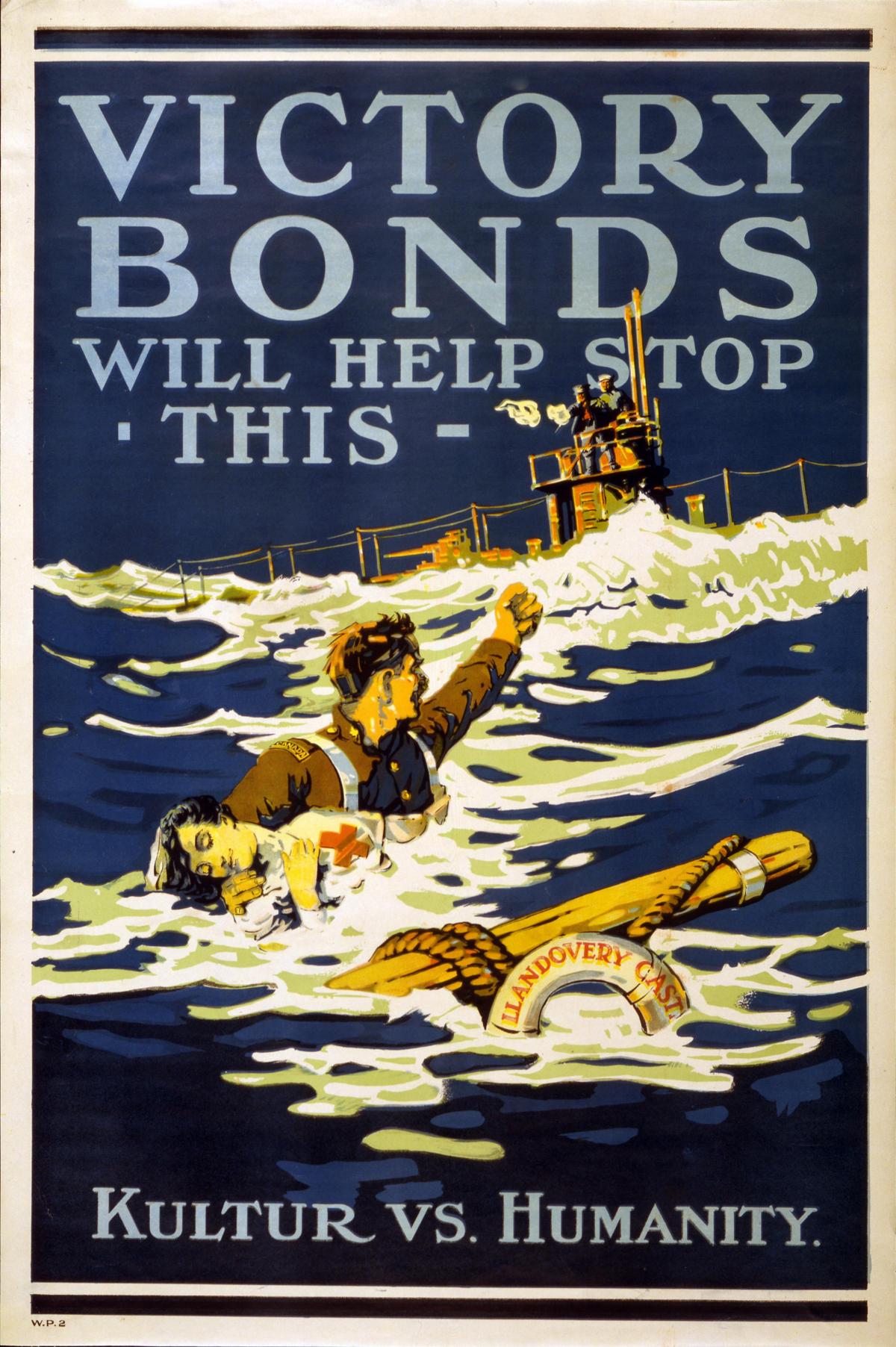

Four months after UC-56 torpedoed the Glenart Castle, the German Navy attacked another hospital ship, the HMHS Llandovery Castle, off the southern coast of Ireland. The Canadian ship was sunk, with the loss of 234 lives.

Such attacks on unarmed ships became a rallying cry for the Allied Powers, who used the tragedies on propaganda posters for the sales of victory bonds, to fund the war effort.

Like the Glenart Castle, the Llandovery Castle had been painted with the Red Cross symbol, and was carrying doctors, nurses, medical staff, and patients when it was attacked.

Mr Hemmings said the waters west of Britain were teeming with German submarines, and all ships which sailed through the Irish Sea ran the risk of being hunted down.

“It was very common to have U-boats in the channel,” he said. “There are wrecks all around the coast of Wales, of U-boats and the ships they sank.

“Once the U-boats had found a way into the Irish Sea - where they could disrupt traffic to Ireland, the USA, and South America - they made numerous return visits.”

A memorial stone to HMHS Glenart Castle in Hartland Point, Devon. Picture: Wikimedia/Etchacan1974 (under CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Glenart Castle came to rest approximately 10 miles west of Lundy, off the Devon coast. In recent times, the wreck has been visited by several diving expeditions, including a British Armed Forces diving team which placed a commemorative plaque on the ship in memory of the 162 people who died.

Picture: Wikimedia/Chmee2 (under CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Merchant Marine crew who lost their lives are remembered on the Tower Hill Memorial in London (above). The RAMC officers and men, the two chaplains, and the eight nurses who died are remembered on the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton; and a memorial in Hartland Point, Devon, commemorates all those who died.

“The Glenart Castle is still remembered and commemorated in military and naval medical circles,” Mr Hemmings said.

- Mr Hemmings would like to track down any living descendants of the 11 Newport people who died when the Glenart Castle was sunk. If you would like to contact him, email nicholas.thomas@newsquest.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here