WITH all the rain we've had recently, we're all reminded that this is the time of year when parts of Gwent are susceptible to flooding.

Who can forget the scenes from earlier this year with vast swathes of land under water and homes and businesses wrecked due to the floods?

And flooding is not a new phenomenon in the area - hundreds of years ago in 1607 those living along the banks of the River Severn were subjected to what may have been a tsunami.

Marks on the walls of churches tell the story of the cataclysmic event. Some are plaques, some are metal, some are merely notches chiselled in the stone, but they all record how high the waters of the great flood came in 1607. Some show the waters having reached a height of 7.14 metres.

An account written in 1607, by William Jones of Usk, told how at around 9am on Tuesday, January 30, the sun was shining and people were working in the low-lying fields of the country bounding the Severn.

But out in the open sea between north Devon and Pembrokeshire was a wall of water speeding towards them. It was at that point just under four metres high, but as it entered the funnel-shaped Bristol Channel, the wave grew taller and by the time it reached the Monmouthshire coast it was 7.5 metres high.

MORE NEWS:

- Look who’s just been in court from Newport and Caerphilly

- 'Huge concerns' for Gwent cancer patients due to fall in referrals

- Wales could be home to one of seven new UK spaceports

The wave became faster and faster as it sped up the narrowing channel. By the time it hit Monmouthshire it had reached more than 38mph - faster than a man could run.

It crashed against the coast at Peterstone, then St Brides, Goldcliff, Redwick and Magor before hurtling inland for up to four miles.

Jones described it as "huge and mighty Hilles of water, tumbling one over another, in such sort as if the greatest mountaines in the world” overwhelmed the land.

At least 2,000 or more people drowned, and almost 200 square miles of farmland was inundated and livestock destroyed along the coasts of the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary.

An account called “Lamentable newes out of Monmouthshire in Wales” by William Welby tells of parishes (spelt as they were then) “spoiled by the greevous and lamentable furie of the waters: Matharne, Gouldenlifte, Portescuet, Nashe, Lanckstone, Bashallecke, Roggiet”.

He added: “So violent and swift were the outrageous waves that in less than five hours’ space most part of those countries (especially the places that lay low) were all overflown, and many hundreds of people, men, women and children, were quite devoured; nay, more, the farmers and husbandmen and shepherds might behold their goodly flocks swimming upon the waters - dead.”

A pamphlet produced by William Welby in 1607 telling of the 'Lamentable newes out of Monmouth-shire in Wales'

The walls of churches along the Gwent coast testify to the flood that happened that day.

At St Brides Wentlooge the plaque inside the porch marks the level of the flood. It reads: "THE GREAT FLVD, 20 IANVARIE, 10 IN THE MORNING, 1606-7". St Peter’s church at Peterstone Wentlooge has one placed at about six feet above ground level, Redwick church has its markers too.

How high the great flood of 1606 reached on St Thomas’s church in Redwick and, right, in closer detail. Pictures: Chris Tinsley

In Nash there is a small mark on the corner of the church tower marking the height reached by the flood, while at Goldcliff a plaque on the north wall of the church marks the height of the flood, stating: “On the XX (20th) day of Ianuary even as it came to pas/ It pleased God the flvd did flow to the edge of this same brass/ and in this parish theare was lost 5000 and od pounds/ Besides XXII (22) people was in this parrish drown.”

A plaque at Goldcliff church commemorating the flood. Picture: Robin Drayton

Many of the plaques mark the date as January 20 1606 because this was the date using the Julian calendar which was replaced with the Gregorian calendar at around this time. The newer calendar, which we still use gives the date as January 30 1607.

Why did it happen? There are two main theories. For many years the accepted explanation was that the flood was caused by a storm surge. This is when very high winds coincide with a high tide and a period of very low pressure. The low pressure and the high tide cause sea levels to rise and the wind forces the sea higher, overwhelming flood defences and inundating low-lying land.

But research paper by Professor Simon Haslett and Australian geologist Ted Bryant of the University of Wollongong, suggested that the flooding may have been caused by a tsunami.

Accounts of the time are similar to those heard following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. The wave of a tsunami is often described as having smoke or sparks flying from the top. Perhaps this is an illusion created by the mist coming off the crest of the wave and the sun catching the spray, but it is mentioned in contemporary accounts.

William Jones wrote of the wave at the time: "Sometimes it so dazled the eyes of many of the Spectators, that they immagined it had bin some fogge or miste, comming with great swiftnes towards them: and with such a smoke, as if Mountaynes were all on fire."

Tsunamis are often caused by earthquakes or landslides under the sea, which Haslett and Bryant say happened off the coast of Ireland at the time.

To people at the time, there would have been only one explanation - that it was the will of God. In Jones' account, he begins by describing the flood as "God's warning to his people", telling of "his most Wonderfull, and Miraculous workes, by the late overflowing of the Waters, in the Counties of Munmoth, Glamorgan, Carmarthen, and Cardigan, with divers other places in South-wales."

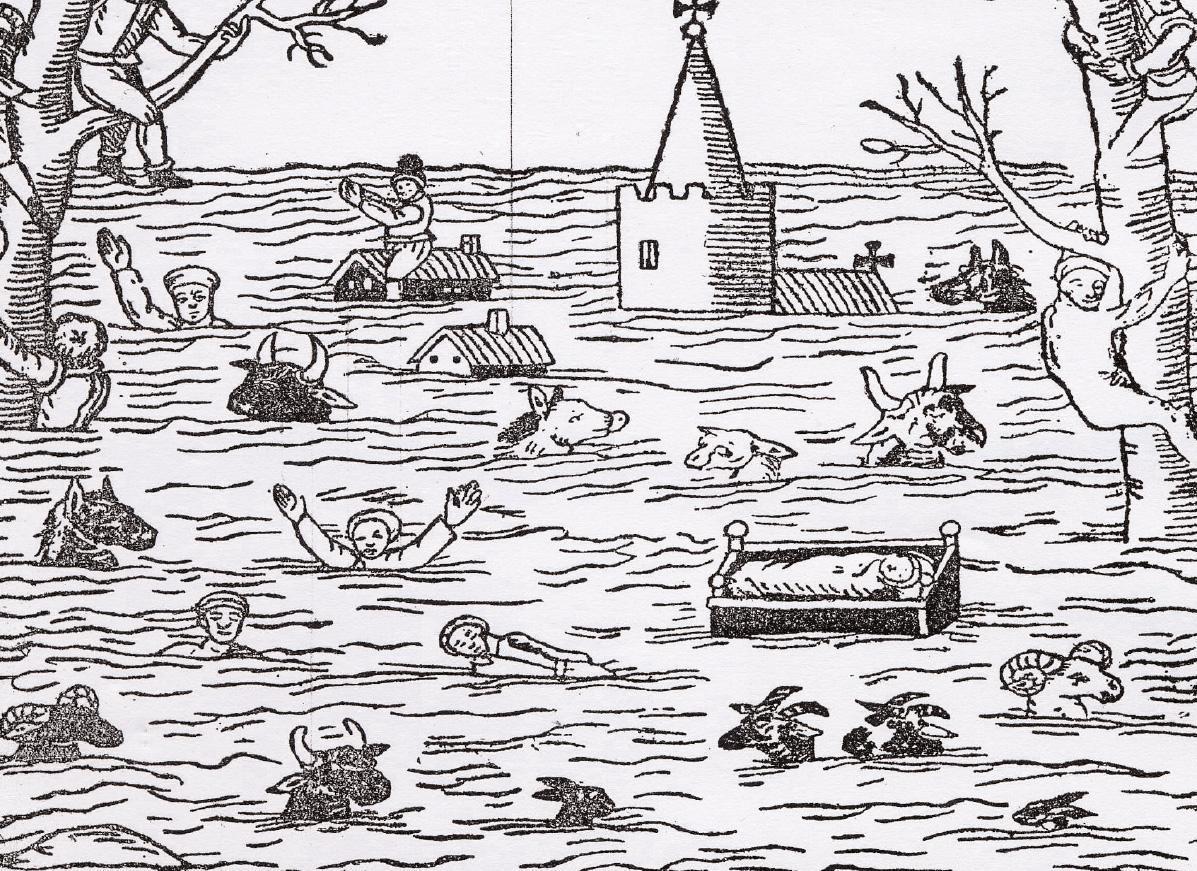

A contemporary woodcut picture of the flood which hit coastal Gwent

The vagaries of weather, disaster life and death all happened according to his will: "Many men that were rich in the morning when they rose out of their beds, were made poore before noone the same day: such are the Judgements of the Almightie God, who is the geuer (giver) of all good thinges, who can and will dispose of them agaiyne at all times, according to his good will and pleasure, whensoeuer it shall seeme best unto him.”

It's perhaps fitting that the record of what was then believed to be the most destructive act of God should be remembered in churches along the Gwent coast. As recent events have shown us, regardless of what or who is responsible, there still lurks the capacity to lay waste much of our part of the world.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel