On Good Friday 1921, John Kyrle Fletcher, a local historian from Newport and frequent contributor to the Argus, took a drive around the Caldicot Levels. He wrote about his journey in the Weekly Argus on April 2, 1921. We re-print it here with comments (in italics) by Peter Strong, secretary of the Gwent County History Association and volunteer with the Living Levels project.

In the land of the reens

Easter exploration of the Welsh Holland

By J Kyrle Fletcher

IT WAS at the fifth milestone out of Newport on the high road to Chepstow that we turned sharply to the right towards the land of the reens.

The tourists who wrote our famous books on the topography of South Wales travelled on foot or they hired a nag; but – other days, other ways - we set out to explore the unknown regions of the Caldicot Level in a motor-car.

Good Friday 1921 fell on March 25. The Argus reported: “The most perfect weather prevailed during Good Friday, and everybody apparently chose to spend the holiday out-of-doors. Warm sunshine and spotless blue skies continued throughout the day and as much as eleven hours sunshine was recorded at most resorts. Newport was no exception to the general rule and at one time the thermometer reached 62 degrees. This is the highest figure yet recorded this year, and is much in excess of the record taken on Good Friday of last year (45 degrees).

It was obviously an exaggeration to call the Levels ‘unknown regions’. Certainly there was a lot of contact between the local farms and Newport itself, with farmers and their families coming in to the provisions market and cattle market.

Fletcher continued:

The Llanmartin lane is as pretty a bit of rural country as will be found. Quaint old cottages stand back from the road, while the first flowering shrubs make a brave show round the door. The flowering currant seems to be the favourite, and its gleaming masses of pin blossom give a true spring tint to the glimpse of a picture we catch as we go by.

Llanmartin village a century ago. Picture from Caldicot and the villages of the moors in Old Photographs by Richard Jones, published by Old Bakehouse Publications, Abertillery

All the world and his wife are out in the gardens, the men busy digging and the women planting seeds, when they do not stand to gossip with a neighbour in a garden over the way, or to shout in clear tones a word of warning to the children who are busy picking primroses.

From central Newport, Fletcher would have driven along Chepstow Road, through the already built up area of Maindee, past the Royal Oak at the bottom of Christchurch Hill and past the Coldra Woods. Obviously, no Coldra roundabout or M4, just a straight road out towards the village of Langstone, where he turned off near the New Inn.

Fletcher continued:

The square tower of Llanmartin church stands out above the bare trees, then next moment we are down the hill in the centre of the little village, and its straggling houses are left behind as we mount the long slope towards Magor.

To the left across the fields stands the future home of Viscountess Rhondda, Pencoed Castle, now in the hands of the modern restorer, who is replacing the worn out stonework and the lost rows of turrets and making this fine old Tudor castellated mansion into the finest Tudor building in Wales which is still habitable.

Pencoed Castle

Pencoed Castle was built in the 16th century on, or very close to, a Norman castle. It was owned by members of the Morgan family from about 1470, eventually becoming part of the Perry-Herrick Estate, which owned a great deal of land around Llanmartin, Magor, Redwick, Undy, Bishton, Penhow etc. and then in 1914 by Lord Rhondda of Llanwern.

His daughter, Margaret, Viscountess Rhondda, well-known suffragette, famous for trying set fire to a post box in Risca Road, Newport, had inherited the castle following the death of her father in 1918. She spent £50,000 restoring it. By 1921 it was in a good enough state for her to host a meeting of Magor Farmers’ Association there.

However, the restoration was never finished, partly because the slump in the coal industry meant that Margaret’s fortunes were declining. Since then it has gone through several owners and was sold again in the summer of 2020.

Fletcher continued:

The banks rise high along the lane, with woods carpeted with frail white anemones, the happy hunting ground of the wild rabbits which cock up their ears with startled surprise as we go by, and the last we see of them is a score of bobbing white tails.

To the right, a short distance from the road, is the tiny church of Wilcrick, a village of 29 inhabitants. I am not going to speculate on the meaning of Wilcrick, but will say it has provided material for much writing by the experts on Welsh place names, and is considered rather a puzzle.

The road has now reached the dead level of the moors, and the ditches are getting wider as we draw near to the metropolis of the moors, Magor, a curious old place, which strikes one as having been far more important in other days.

There are several charming old houses in the village. One with a large pointed Gothic gateway and some early windows, many of them filled up and only showing the traces of their dripstones. Another quite small house near the Church is an excellent example of Tudor building, with three and four Perpendicular windows and doorways.

In front of the Church are the remains of a fine mansion house; a few tall crumbling walls, with empty window spaces and broken doorways, are all that is left of the old manor house, where a branch of the powerful Herbert family once lived.

The house near the church was known as Church House and was described by Fred Hando two years later as 'an unspoiled relic of Tudor England'. It was demolished in the 1960s but a window and stairway can still been seen at the edge of Magor car park.

Procurator's House, Magor. Picture: Peter Strong

The so-called mansion house is known locally as the Procurator’s House, a Procurator being an official responsible for collecting taxes on behalf of the Roman Catholic Church in the days before the Reformation. However, the house was not built until after the Reformation and so was never actually a procurator’s house. It may well have been the home of the parish priest.

Fletcher continued:

The church stands high above the ruined mansion, and is one of those old buildings about which your learned antiquary loves to write.

Each period of church building seems to be represented in this old grey structure, which was probably quite a small church at first, but grew larger as various portions were added to the fabric.

It has a fine square tower in the centre, and a clock which keeps good time, as it should do, for it is close to the main railway line to London, and the busy merchants from Cardiff, as they go by in the fast express, can catch a glimpse of the clock and speculate on how many minutes late the train will be arriving at Paddington.

The part of Magor Church I like best is the Tudor porch, built in the reign of Henry VIII, with a room above, which was once the Church library.

'The cathedral of the moors', Magor Church. Picture: Peter Strong

There was not much church building in the reign of Bluff King Hal, most people were too busy gathering Church spoils to trouble about building.

The builder of this porch was, I feel sure, proud of his work, for he has put his name on a label over the door, where it still stands out clearly, “Toft”.

Holland in Wales

Crossing the railway line by the bridge at Magor we drop down on to a stretch of dead level road, with rows of willow trees fringing the broad reens.

Here and there, by a solitary farmhouse, stands a row of tall elms, from which the busy sounds of a colony of rooks fill the air with that curious monotonous cawing. These long straight roads have a most unfamiliar look, and remind one of those old Dutch paintings by Cuyp or Ruysdael. Perhaps it is because we are so close to the sea that the clear silvery light is much the same as we find expressed by those great painters of Holland.

In fact, I have heard this long stretch of country called “Holland in Wales”.

'Holland in Wales' - a reen near Redwick. Picture: Peter Strong

At Redwick we turn sharply to the right, and the keen air reminds us that, somewhere away beyond the dyke in front, the open expanse of the Severn Sea lies. But you never see it, for really we are below it’s usual level on this stretch of reclaimed land.

The Romans are believed to have first built the sea walls, and also to have enjoyed the sport of catching the wild fowl which in olden times flocked to these levels.

But the monks of Goldcliff cleaned and reclaimed the land, and built roads through it. Today the bulk of this land belongs to Eton College.

It was Henry V, Hal of Monmouth, who turned out the alien monks and granted their lands to native institutions. But when the Priory of Goldcliff came to be dealt with, he gave the Priory and its lands to the new college at Eton.

Sea wall at Redwick. Picture: Peter Strong

Contrary to Fletcher’s belief, the Romans did not build the sea wall as he knew it, since the sea level was much lower then. Rather than building a continuous sea wall the Romans may have built sections of embankment to form enclosures of reclaimed land. They also built drainage ditches.

By the Middle Ages, however, a sea wall was needed.

In 1424 the prior of Goldcliff complained about coastal erosion and flooding, stating that “…half the parish church was destroyed by the sea” and that the priory itself was in danger.

Thirtennth century charters for Goldcliff refer to the workings of the drainage system and the monks are reputed to have built the “Monks Ditch”, the main drainage channel through the Levels.

Nothing of the priory remains to be seen above ground now.

The reference to turning out the alien monks refers to the fact that as a Benedictine monastery founded in the 12th century, its mother house was Bec Abbey in Normandy, but it was actually Henry VI, not Henry V, who, in 1450, made it a cell of Tewkesbury Abbey and granted the revenue to Eton college. This included the fishing rights and Goldcliff become well known for its salmon fisheries.

It is reputed that once a year salmon captured on the putchers would be sent to Eton College to feed the masters (and possibly the pupils).

At the time of Fletcher’s visit, the salmon fishery was operated by Edgar Fennell. The Fennells had been selling fish in Newport since 1840. Their shop was at 11 High Street, at the top end of the Market Arcade, which was known as Fennell’s Arcade.

Fletcher continued:

The Great Flood

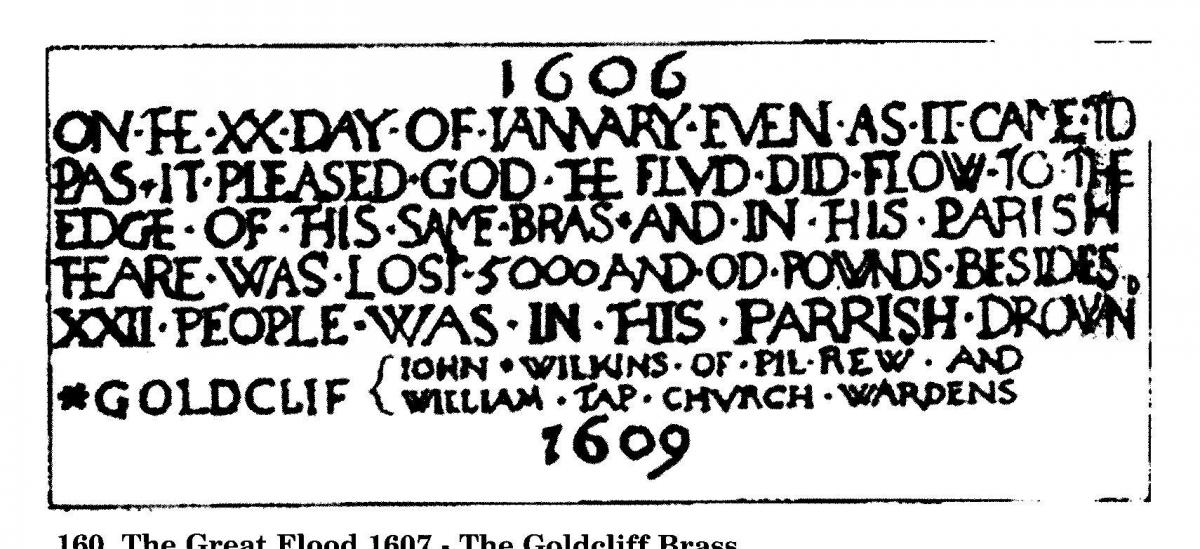

At Goldcliff Church a plate on the wall tells of the great flood of 1607, when Cardiff lost its principal church – the Church of St Mary, on the quay. What a deluge it must have been to have reached such a height!

But such an event is not likely to happen in these days. The sea walls are too well looked-after by the Commissioners of Sewers, and the locks and reens kept clear.

But one can quickly see how the flood, if once it broke in, would sweep the land for miles.

The plaque gives the date of 1606, rather than 1607, because the flood happened in January and in those days they counted the new year from March. The inscription reads: "On the 20th day of January even as it came to pass, It pleased God the flood did flow to the edge of this brass, And in this parish there was lost 5,000 and odd pounds, Besides 22 people was in this parish drowned".

Goldcliff plaque drawn by Fred Hando

Fletcher continued:

In all the distance we have travelled, we have never once lost sight of the hills beyond. The long range of the Mynydd, Mynydd Machen, the woods behind Cefn Mably, and the spur of Cefn On above Caerphilly, have stood out clear, so that by their changing position we could tell our position; while, on the other side, the sharp peaks of Wentwood have filled the background.

From Goldcliff, with its little white cottages and busy quacking ducks, we turn back towards the higher land. Here the deep reens are red with duck-weed which grows so thickly that it covers the water completely, and leaves only a red way under the willow trees.

Duck-weed is normally green. It was reported at the time that this was the only place in Monmouthshire where it was red and that locals believed this was because Lord Rhondda of Llanwern House had brought a sample of the red weed with him back from the USA in a match box.

Fletcher continued:

By Cold Harbour and Pye Corner, relics of ancient times, we come on down the long straight road bordered with willows, a water course on either side, till suddenly a huge mass, a skeleton of ironwork, rises in front. It is the Newport Transporter Bridge, which we approach end on.

Near Liswerry the Easter crowd have come out to the football match, but we are going home with thoughts of a cup of tea and Easter cakes, and have no thought for football. A Welsh club or an English one may win today, but we are homeward bound.

A season record crowd of 16,000 people was on its way to watch Newport County play at Somerton Park. Fletcher’s comment that a Welsh Club was playing an English one may be surprising since Newport were playing Merthyr Tydfil. Perhaps he wasn’t interested in football and didn’t know who was playing or perhaps he regarded Newport, being in Monmouthshire at that time, as an English club. Merthyr won the match 3-0, but County soon got revenge, winning the return fixture on Easter Monday.

- Membership of Gwent County History Association is open to anybody with an interest in local history within the county of Gwent. Members receive a copy of our journal Gwent Local History twice a year. For more details see www.gwenthistory.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here