THIS year marks the 20th anniversary of the opening of the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff Bay, which has since welcomed 30 million visitors through its doors.

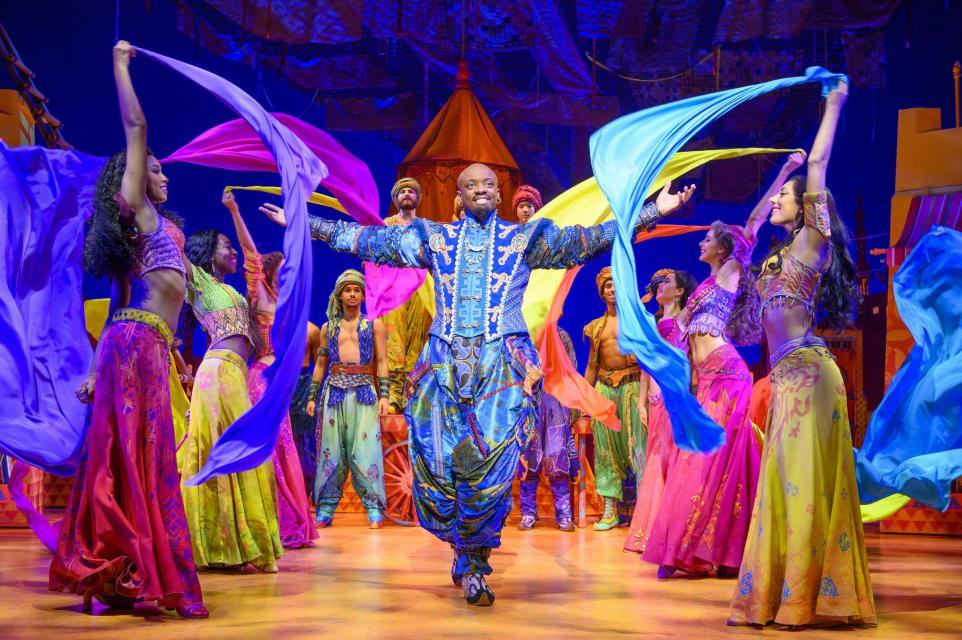

Despite weathering various economic challenges throughout the past two decades, including a recent 10 per cent budget cut to Arts Council Wales, the WMC has enjoyed relatively stable commercial success as one of Wales’ crucial economic drivers, hosting shows like Hamilton, which comes to the stage in November this year.

Funded by the Welsh Government and National Lottery Millennium Fund, the Centre was designed by Jonathan Adams of Capita Architecture (formerly called Capita Percy Thomas).

The building represents both natural and man-made elements of the Welsh landscape. The slate slab walls exterior collected from Welsh quarries represent the tones and textures of coastal cliffs, and the Copper-coloured hammered steel dome pays homage to the once thriving steel industry.

The 1900-seat theatre and 250-seat studio theatre is a vital performance venue for both visiting and resident performing groups, such as the BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales, Welsh National Opera and National Dance Company Wales.

However, less is known of the controversy surrounding the events involving the construction of the iconic venue.

Before plans to build the Wales Millennium Centre were conceived, plans to use the site as the Cardiff Bay Opera House were in the works to construct a permanent home for the Welsh National Opera.

Following a prestigious international design competition, the project was won by now world-famous Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, whose imaginative ‘inverted necklace’ design featured two glass buildings wrapped around each other, an ambitious project unlike anything else ever seen before in Welsh architecture.

However, despite winning the competition, Hadid never saw her construction come to life.

In an unprecedented move, Former Secretary of State for Wales Lord Crickhowell asked Hadid to resubmit her design following concerns that the style was overly ambitious, although according to experts at the time, it seemed achievable in terms of time period and budget.

Again, Hadid confidently won the re-round against fellow runners up Norman Foster and Manfredi Nicoletti. Not only had Hadid yet again proved that her design was the best, but she had demonstrated her dedication and devotion to her vision.

However, despite Hadid’s innovative and imaginative design, the project was deeply unpopular and lacked support from locals and politicians, criticised for being ‘elitist’ and ‘ugly’.

Following intense media scrutiny, the project failed to secure backing from South Glamorgan County Council or Cardiff City Council as it was viewed as too financially precarious.

Following years of extended proposals and deferrals, the project was eventually abandoned by the Millennium Commission (acting as the project’s funding body) for being too radical and avant-garde.

Hugh Pearman, architecture critic for The Sunday Times pointed to the continuously fraught relationship between London-centric cultural initiatives and the degree of devolved Welsh control, in particular, the UK based Millennium Commission’s involvement in the project.

Although the plans for Cardiff Bay’s most ambitious Opera House project were foiled, Hadid’s design was eventually used to build China’s Guangzhou Opera House in 2010.

The failure of the Opera House seemed to have little impact on Hadid’s subsequent success as an architect.

Following the incident in 1995, Hadid went on to become one of the most influential architects in the world, going on to design Rome’s MAXXI Museum in 2010, and the London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympics.

Hadid is remembered as an architectural visionary, in particular for her unprecedented achievements as a female ethnic minority professional striding forward within a white male-dominated industry.

It remains that the origins of one of Wales’ most iconic buildings is in fact rooted in a complex set of controversial decisions and circumstances.

What could have been Wales’ most innovative and forward-facing architecture project will now, in the words of former Cardiff city councillor Alun Michael, be "the most famous unbuilt building in Wales."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here