This week, we continue with Fred Hando’s ‘Rambles in Gwent’ and visit Llanvetherine.

IS the pulpit losing its power? Often have I taken part in arguments around this vexed question. Recently I discovered evidence which I shall hold in readiness for future debates on the topic. Cruising lazily along the Ross-Abergavenny road, I saw an interesting church tower.

The upper portion of the tower was wider than the lower part, being supported on corbels.

Bright sunshine flooded church and churchyard, inn and farmsteads. The village was Llanvetherine, midway between Cross Ash and Abergavenny, Lovers of the church had brought the brightest gifts from their gardens in readiness for the Sabbath.

Daffodils, primroses and fruit blossom expressed the ecstasy of springtime, but four of the windowsills in the nave were filled with red, white and blue anemones—a floral prayer for the Queen in her coronation year.

I absorbed their glory as I stood at the entrance. Then I realised that near me was a presence.

Leaning against the wall of the porch was a big stone slab on which was carved the figure of a saint with upstretched arm. This was St Gwetherine, to whom the church was dedicated, and after lying for many years untended in the church-yard the slab had been brought into the shelter of the porch.

I noted the northern deflection of the chancel. I read many of the interesting memorial inscriptions.

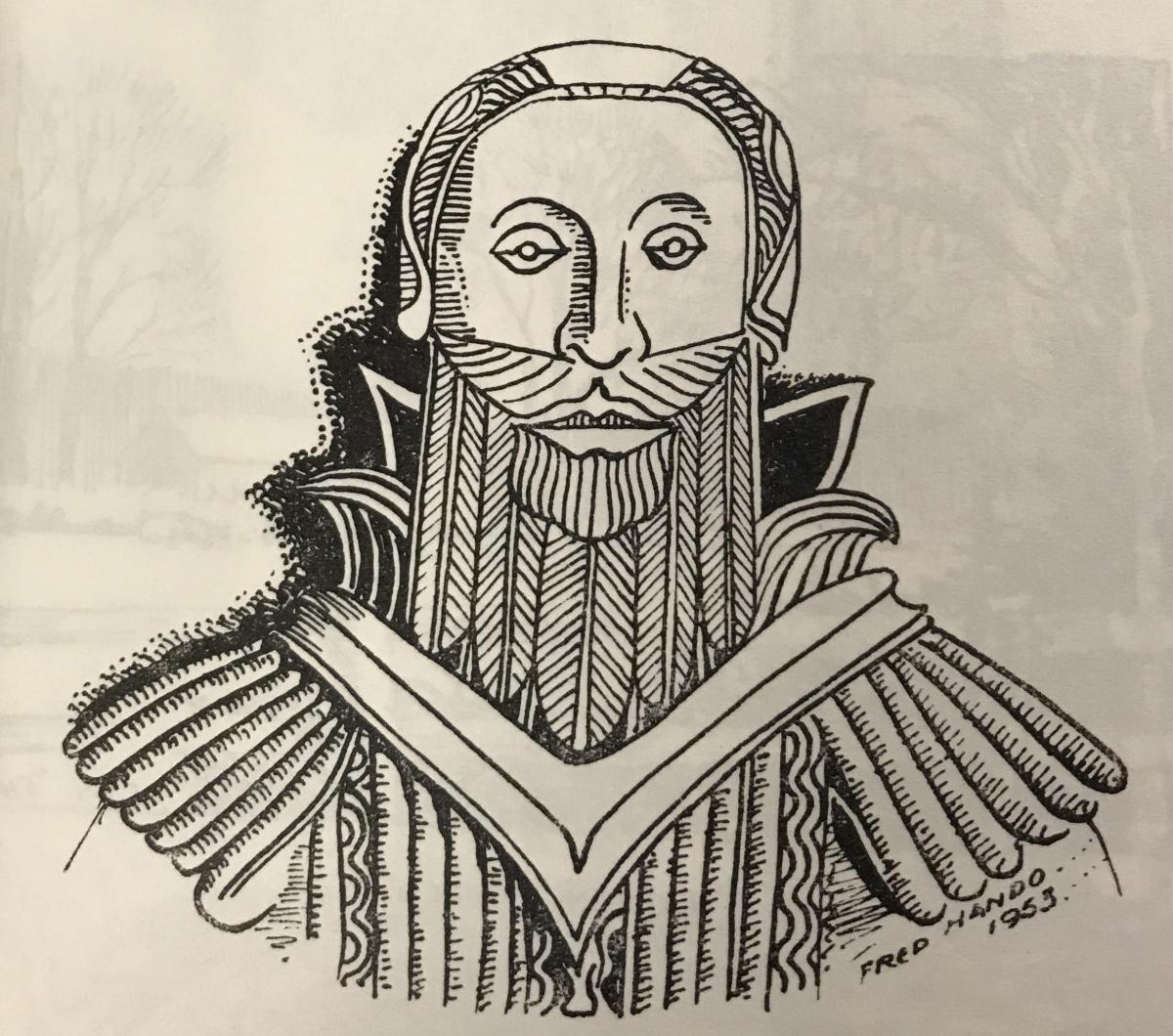

Then suddenly I was confronted with two extraordinary stone portraits, resting against the east wall of the chancel. The Rev. David Powell, Vicar of Llanvetherine, who died in 1621, is shown on the right-hand stone.

His head rests on a cushion; he holds a Bible. His cloak, edged with a decoration of oak leaves and acorns, is thrown open to display a tunic with knotted belt and knee-breeches with no “bombast.”

Fine as these clothes were, they lapsed into insignificance beneath the splendour of the vicar’s facial embellishments. A moustache of noble proportions, hoisted well above his upper lip, sweeps thence to the ears. Pendent from the lower lip is a special beard, well-ordered, covering with fair precision the shapely chin.

The beard proper, believe it or not, is disposed in five plaits, each of which reaches to and emphasises the line of the collar. Surely such a cleric, high-perched in his three-decker pulpit, began his ministrations with such notable personal advantages that none of our clean-shaven parsons could hope to equal.

The Rev David Powell, could he be brought to us in all his glamour, would fill St. Paul’s with enthusiastic congregations, and incidentally would substitute for the sad uniformity of the masculine visage some of the charming variety of a more spacious and leisured age.

What would I give, for instance, to see my friend, Alderman, complete with a handlebar moustache and a five-plait beard?

The vicar’s wife, whose effigy stands to the left of the pulpit, is a figure of womanly grace and sweet piety.

Some miscreant has carved the date, “22 of April, 1715,” on the stone, but Mistress Powell’s three-tiered ruff enables us to accept the two portraits as contemporary. Between the candles rises from her shapely head the high-crowned hat which should make Llanvetherine a port of call for every student of Welsh costume.

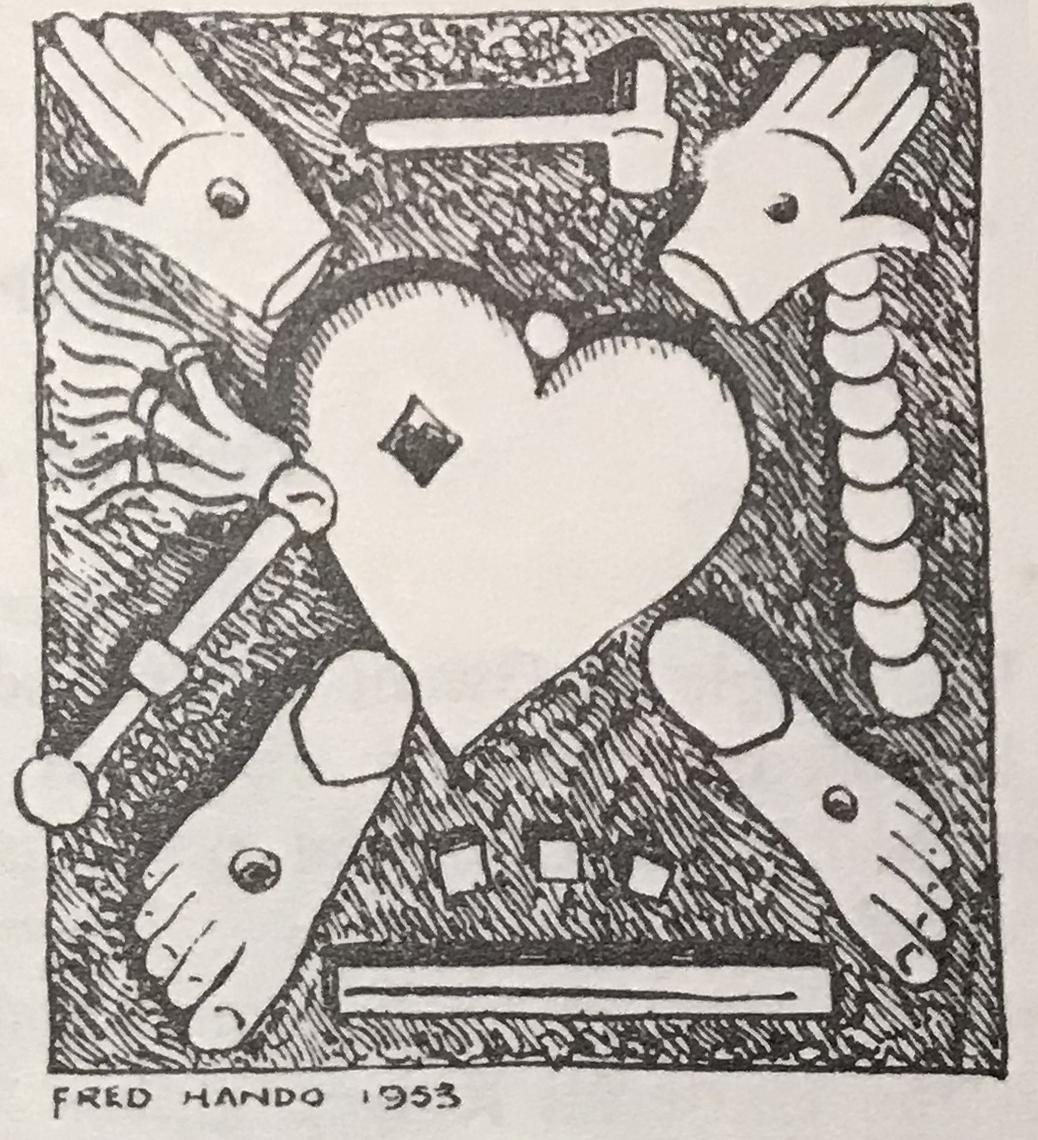

The ring on the second finger of her right hand reminds us that until 1549 the wedding ring was worn on the fourth finger of the right hand. The sculptor has solved the difficult problem of the front view of the lady’s feet by giving a side view. His rendering of the vicar’s feet is more successful. I cannot hope to do justice to all the treasures of this country church, but must describe the carving on the oat tablet fixed on the west wall of the nave.

As my sketch shows, the “five wounds’ of our Saviour are shown, and among them are “The Instruments of the Passion”—the dice, coins, hammer an scourge—all rendered with a loving touch and a child-like simplicity.

Out in the sunshine again, I asked my way to Caggle Street. I found it around the bend to the east of the village—a steep “street” climbing the hill, it seemed, to nowhere.

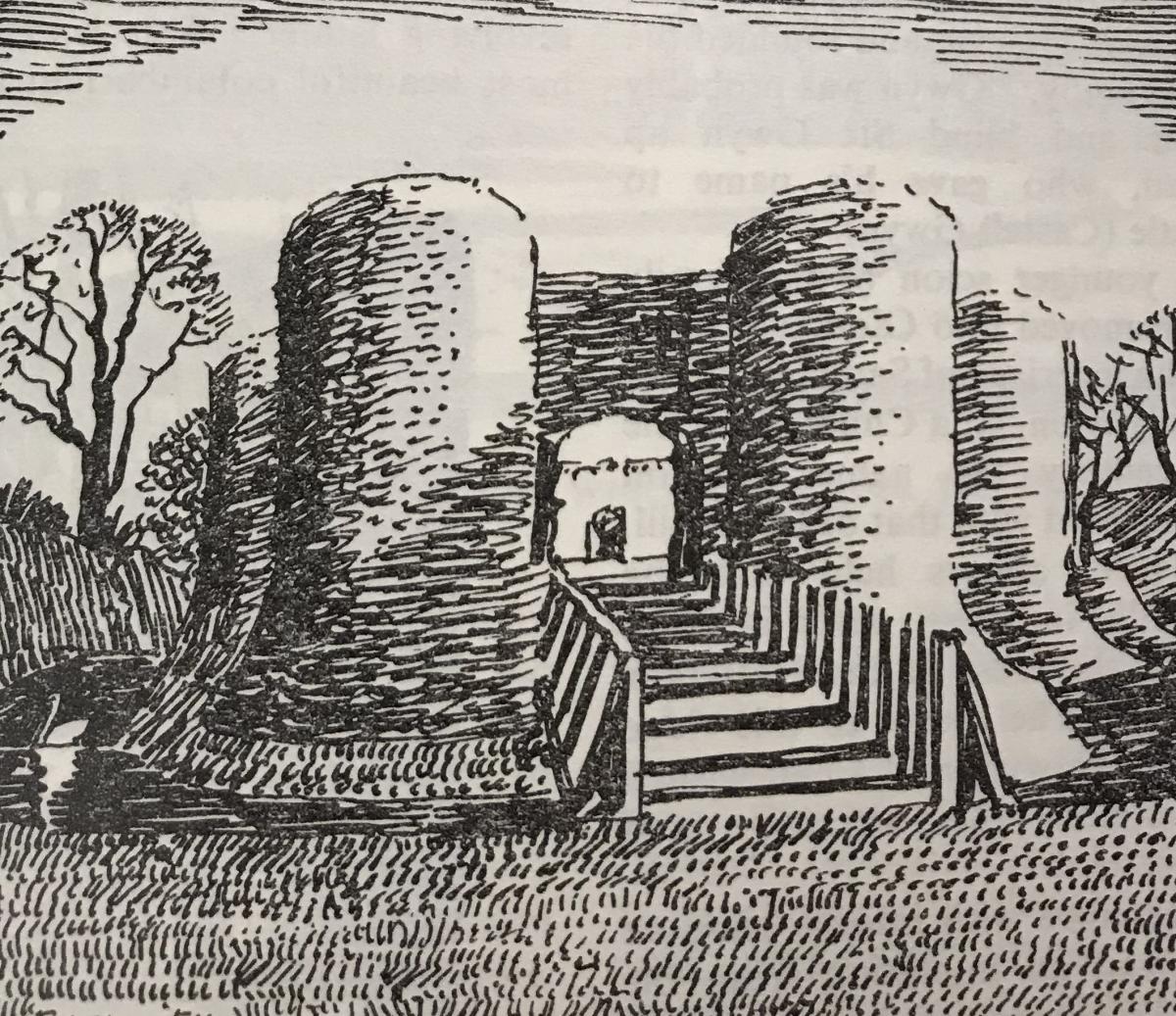

“Could you tell me,” I asked a lady of Caggle Street, “the meaning of `Caggle ‘?” “Oh yes,”—with a smile—” `Caggle’ means `dirty,’ stony,’ and so it was when it was the Roman road leading from White Castle to the Skirrid.” From her flower-filled garden I got a good view of White Castle, and from the top of Caggle Street an imposing prospect of the mile-long ridge of the Skirrid.

Fred Hando’s works appear courtesy of Chris Barber.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here