This week, we turn to Fred Hando’s ‘Rambles in Gwent’ with a visit to Trewyn.

THE people of Gwent are proud in the knowledge that the origin of our Prime Minister's Christian name is to be found in our county.

"Trewyn," the stately house under the south-eastern tip of the Hatterall Ridge, implies "the home of Gwyn or Wyn"—in English "Winston."

The name "Trewyn" takes us back to 1091, when Robert Sitsyllt came with Fitzhamon to conquer Gwent. Sitsyllt married the daughter of Gwyn, Lord of Alltyrynys and Trewyn, and founded the great Cecil family. Gwyn was probably the gallant and blind Sir Gwyn ap Gwaethfoed, who gave his name to White Castle (Castell Gwyn).

Later a younger scion of the family of Wynston moved into Gloucestershire, and from the marriage of Sarah, daughter of Henry Wynston, to a Churchill in the sixteenth century the name Winston became associated with that of Churchill.

Now I have always held that the grandest walk in these parts is from Pandy along the crest of the Hatteralls to Llanthony.

The ascent to this ridge took me past Trewyn, and I had wished often to explore this attractive and imposing house. It was therefore with intense pleasure that I received an invitation from the Mistress of Trewyn to visit her home, and to include a description in "Monmouthshire Sketchbook."

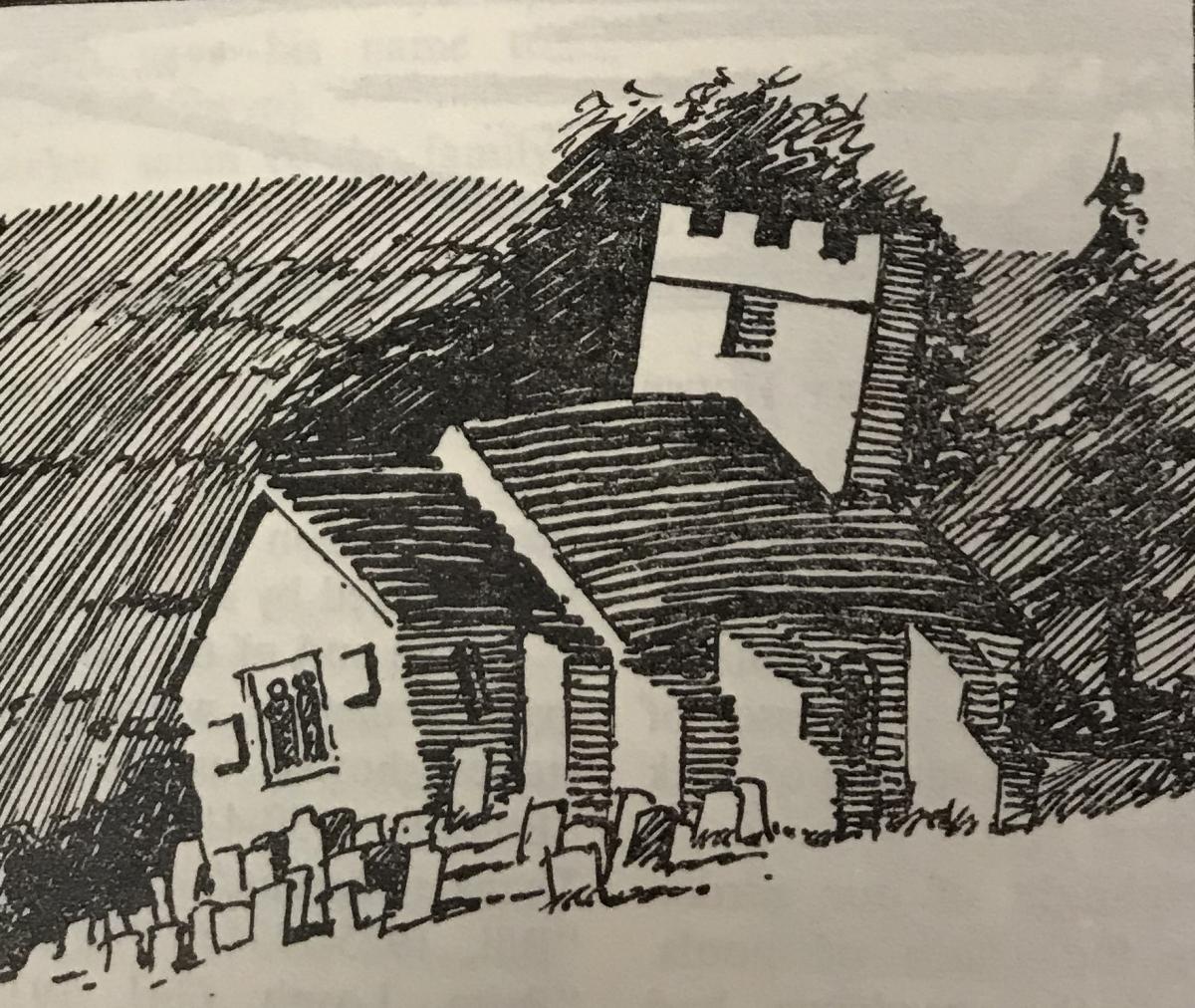

An avenue of Scots firs leads from Alltyrynys to Trewyn. We turned from the Longtown road into a charming lane, and soon caught our first glimpse of the house, resting on the hillside at the summit of a long flight of seventeenth century steps. Our hostess awaited us, and took us at once to see her first treasure.

This was an octagonal pigeon-house, built of bricks which have mellowed to rose-pink. It contains 832 nests, each of which can be reached on an ingenious revolving ladder. This is certainly the most beautiful columbarium in Gwent.

Our tour of the grounds was a long series of spring delights. To list the blossoms would take up all my available space, and my memory is of masses of purple and gold against a setting of pink earth and grey stone.

Perhaps the highlight of our garden walk was along the chain of pools. Here nature and the gardener had conspired to show us just what was possible when the red sandstone soil was watered by a Hatterall stream. At the end of the pools we came to a green cemetery, where miniature grave-stones showed us the resting-places of "Bumble, 1930-41, Canis Fidelis." "The Twins Thomas," "Betsy, 1925-1938," "Bill, 1925-1934," "Batch, 1925-1930," "Brita, Lovely Girl, 1938-1950," and "Cat Tom Pussy, 17."

Our hostess, whose special type of humour appealed to me, referred to one of her dogs as a "Cwmyoy Terrier," and was obviously in the confidence of all her animals.

The inscription above the front door reads "A.D. 1694," and although there were previous homes on the site the present house appears to be wholly of that period.

We examined the ingenious triple lock on the front door, entering then a spacious hall in which tea had been laid for my large party, and this was a delightful introduction into a house which is obviously planned for gracious living.

Our hostess showed us the rooms in turn, each with its own individual treatment, but notably each with its own outlook, and its own comfort.

We saw the splendid portraits of the Molyneux family painted during four centuries, including famous soldiers and administrators, and one sixteenth century lady who lived 162 years.

We admired the proportions of the rooms, the polished oak floorboards, the plaster decorations, the views from the windows.

Best of all, we remember Trewyn not as a showpiece, but as a "tref"—a homestead, set in a green land watered with hill streams, guarded by majestic mountains, the abode of happy, cultured folk.

I cherish a theory that Sarah Wynston took some of the warmth, the ruggedness, the good humour, the imperturbability, the love of good living, the love for the old land, which Old Trewyn gave her, and transmitted all that to her descendants.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here